“Anita Hill Would Have to Agree with Me”: LET’S TALK ABOUT IT Removed from Oak Brook Public Library

Oak Brook is a small town just outside of Chicago, Illinois. It is home to one of the state’s largest malls, as well as an array of restaurants, golf and sports clubs, and other markings of a typical middle to upper middle class suburb. Oak Brook is also home to one of the most unconventional public library setups, both in the area and in the country. There is no formal library board that governs library operations. Instead, the village board operates in that capacity, and while that board appoints a commission to help with library-related policies, that commission operates in an advisory capacity. The commission, which meets quarterly, in its most recent meeting in April 2022–the July meeting was canceled–discussed non-resident library cards, meeting room policies, and heard updates from the director and staff.

With this setup, the director reports to the village board with issues and hears from the village board with issues of relevance to the department.

With this setup, it is also easy for books to suddenly disappear from shelves if someone on the village board decides they don’t like it.

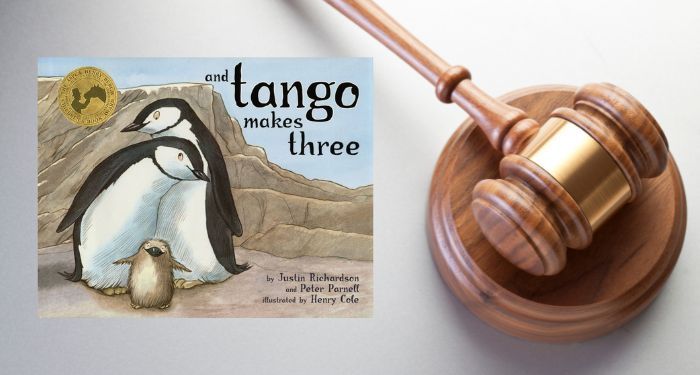

That is exactly what happened in June this year, when a book that has made the rounds across censorship groups caught the attention of Village Board member Ed Tiesenga. Tiesenga, who is a lawyer in Oak Brook, has been on the Village Board since elected in 2015.

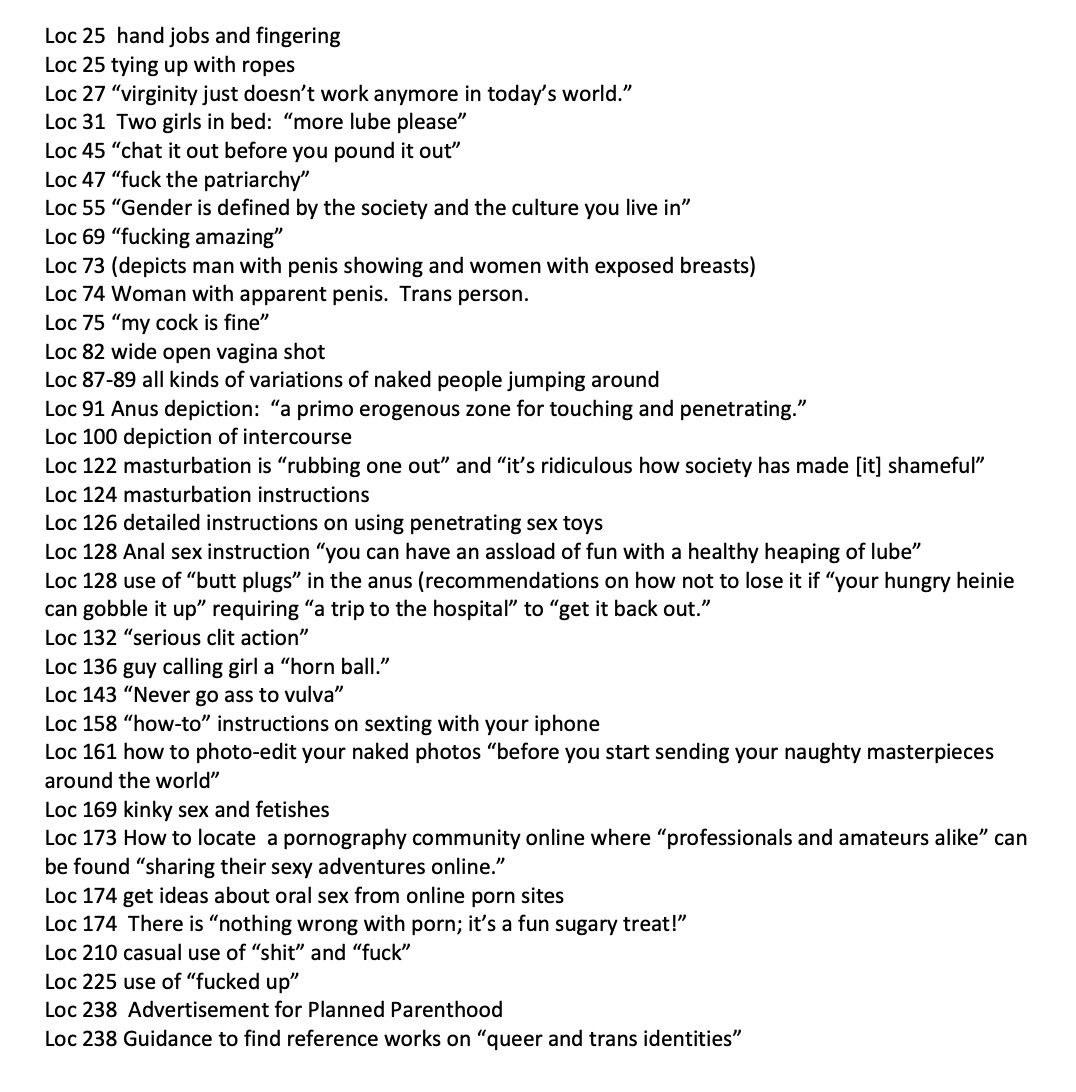

Copying fellow Oak Brook village manager Greg Summers and village mayor Gopal Lalmalani, Tiesenga emailed Oak Brook Library Director Jacob Post, asking if a copy of “the attached book was still available for children to check out.” The cover of the book Let’s Talk About It: The Teen’s Guide to Sex, Relationships, and Being Human by Erika Moen and Matthew Nolan was included as an attachment to the email, as well as the “index to topics.”

The book, published for teens, was available in the teen section of the library at the time. It isn’t a surprise that the locations highlighted above are ones included in the Moms For Liberty review.

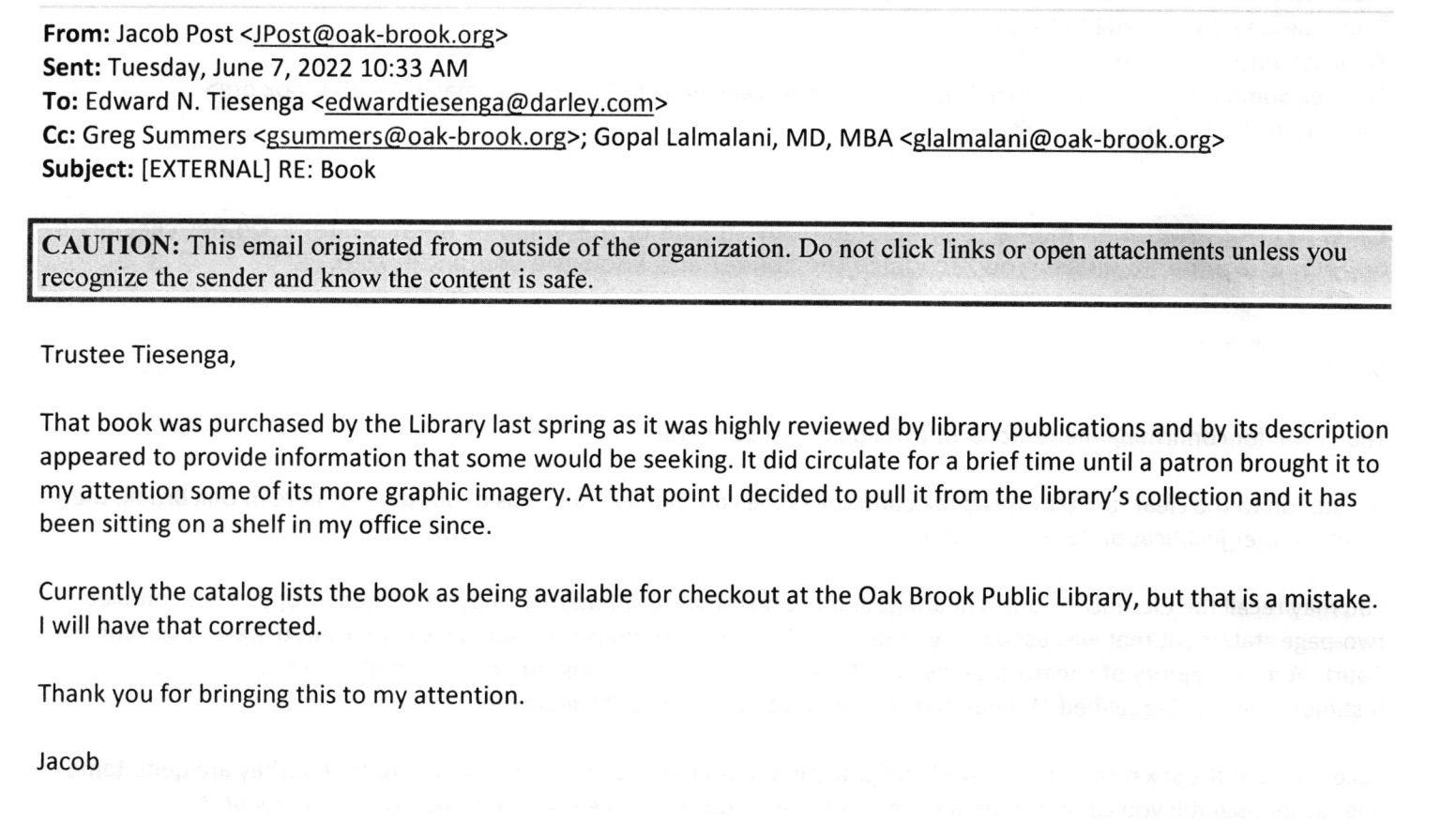

Upon receipt of the email, Post shared that the book, which had received a complaint by a patron, was no longer available to check out. It was, in fact, sitting in his office instead.

This is a classic case of quiet censorship. More, it illustrates the ways administration can both undermine the work of their staff trying to provide materials for patrons, as well as undermine the administration’s ability to seek feedback and a formal review process from a board that works specifically on behalf of the library and its patrons.

Let’s Talk About It is available through the library’s ebook consortium, and it is available at dozens of public libraries throughout the area. But residents of Oak Brook utilizing their own library are unable to pick it up from shelves.

What is equally disturbing, though, is that nothing on the Village Board agenda–nor the recording of the public meetings–discuss anything related to books at the library. Meaning that closed door sessions to discuss library books may be happening or that there are, in fact, no meetings happening at all, and board members are able to use their power to determine what is and is not available to a whole community.

And as much as it is jarring to find this act of quiet censorship happen outside the eyes of a board, library staff, or the library’s community, it is also jarring to read the response Tiesgna shared about the news. Not only was he happy to hear that the book would not be available to “children”–it is a book for teens, put in an area for teens–but it reminded him of the Anita Hill case.

A book featuring honest depictions of sex for teens, as well as an “advertisement for Planned Parenthood,” being compared to testimony from victim of sexual harassment is impossible to articulate. Having access to an age-appropriate book about sex is, in the mind of a board member who is a practicing lawyer, akin to statements about sexual harassment used to end the career of a potential (and actual) Supreme Court justice. This particular line of reasoning for book removal includes a bonus ding at the current president and members of the democratic party more broadly.

Public libraries are not neutral. They are nonpartisan. But without proper oversight by a governing board, it is easy for public libraries to become partisan tools. In the case of Oak Brook, a complaint by a board member led to the director pulling a book without any due process. Even if, as Post says, there was a patron complaint, no process to formally review the book happened. It simply disappeared from shelves. Post is in a precarious position: if he removes the book, he censors; if he doesn’t remove the book, his job is on the line, as the village board oversees his position.

Stories like this one go unreported more often than not. In situations where these meetings happen in private or out of the public eye, no one can know what goes on unless there is a paper trail. When organizations like PEN America report on the staggering numbers–and continual increase–of book bans, their numbers do not and cannot reflect the instances that happen outside of the public eye. When those covering censorship talk about the untold stories, it’s stories like these which unfold in quantities we’ll never know.

Oak Brook’s director removed Let’s Talk About It. It’s likely not the only book pulled from the collection or which never made it to the shelves to begin with.

Banning books has become a way for right-wing groups to become heroes and film their 15 minute performances at school boards for sharing on social media. Those book bans hurt people outside of their small, but well-funded, groups.

But what we do not know and cannot know are the communities like those in Oak Brook hurt when politics play a far more important role in public institutions than the fundamental First Amendment rights of those purportedly served.

A teenager who reads a comic book about sex and learns how to navigate the barrage of pornography on the internet, who discovers that the human body is awash in erogenous zones, and can decide how to make choices for their own sexual lives (as teenagers or as adults) is not losing their future potential as Supreme Court Justices.

They never had them to begin with in a system of favoritism or politics. In which there aren’t consequences for actions like sexual harassment of others. In which their rights to access information are taken from them without due process.

Whose community standards are those?