Gay Liberation Front veterans reflect on ‘radical’ changes since UK’s first-ever Pride march

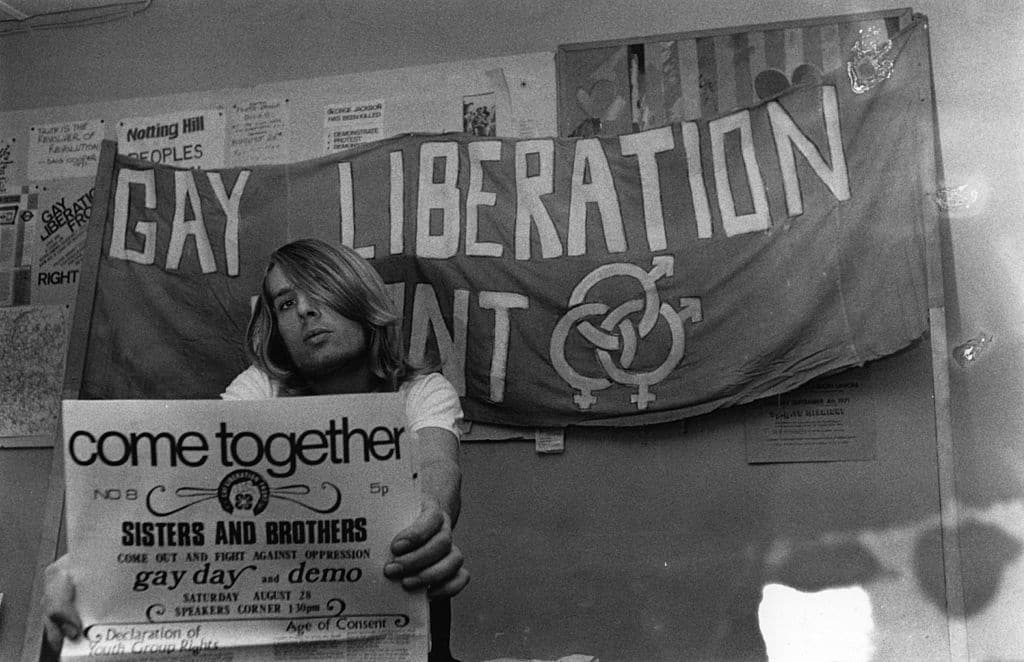

Members of the Gay Liberation Front marching in a historic picture. (Peter Tatchell)

On 1 July 1972, hundreds of queer people marched defiantly through the streets of London to demand that they be treated with respect by a society that loathed them.

It was a seismic moment in what was then a small, burgeoning liberation movement. The queer people who took to the streets that day were angry – they were sick of being policed, sick of being told that they were disordered, and sick of living in a society where their self-expression was strictly controlled.

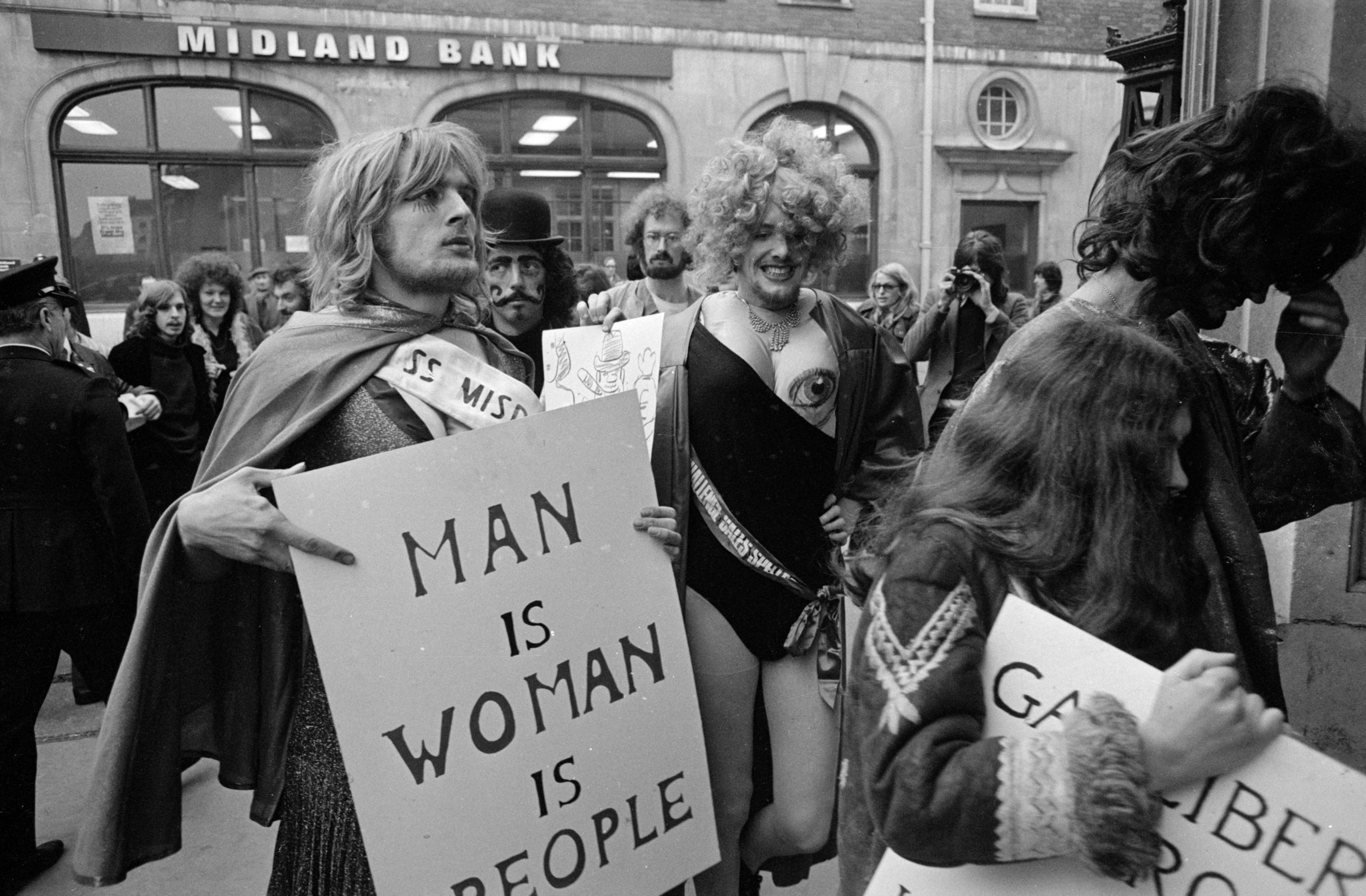

Drawing from the women’s liberation movement and from the fight for Black civil rights in America, around 500 Gay Liberation Front (GLF) activists sent a clear message that they would no longer be silenced.

That march has gone down in history as the UK’s first ever Pride march, even if it wasn’t officially called that at the time. Half a century on, many of those GLF activists are dismayed by where the Pride movement has ended up. Today, police officers and arms manufacturers take part in Pride parades while politics largely takes a back seat.

Veterans from 1st UK Pride in 1972 in Trafalgar Square, where it started. L to R: me, Bruce Howard Bayley, Stuart Feather, Eric Ollerenshaw, Nettie Pollard & John Lloyd

@PrideInLondon @UKPrideNetwork @stonewalluk @PinkNews @gaytimes pic.twitter.com/CX1yTvYWzg— Peter Tatchell (@PeterTatchell) June 20, 2022

That’s why some of those same activists are taking to the streets on 1 July to mark 50 years of Pride. They’re inviting everyone who “can’t stand” the Tory government to join them for a protest that will retrace the exact route of the 1972 march.

To mark 50 years of Pride, PinkNews sat down with Nettie Pollard and Stuart Feather, two of the activists who took part in the original GLF march, to reflect on their history of activism and to find out why they’re staging their own protest march in 2022.

PinkNews: You both marched in the first GLF march in 1972 – what was that like?

Nettie Pollard: I felt at home. It was a lovely experience to be out with so many other LGBTQ+ people. Ever since April of ’71 I’d been wearing a GLF badge all the time so I was very familiar with people’s reactions to gay people. I didn’t feel the least bit worried about the march – for some of the people, it was the most enormous step to go out in public.

Stuart Feather: It felt wonderful. There were maybe 500 of us on it so we felt very secure, very safe, and we were very prepared for all kinds of remarks being made as we passed by. By then the people that I identified with in GLF, we were becoming much clearer in what we wanted to do and what we wanted to be. So we were all in drag and make-up and nail varnish and stuff – not pretending to be women or anything like that, but just men in frocks who could be immediately identified as homosexuals. So that was really exciting.

PinkNews: Nettie, can you tell us a bit about what it was like for women in the gay liberation movement at that time? Was there too much of a focus on gay men?

Yes, I would say so. Also it’s that we were outnumbered by the men. I mean there were at least five times as many men as there were women there, so that’s partly why we started off by having a separate women’s group which met on a Friday. We would go to the general meeting on a Wednesday, and some people only went to the women’s group – we could talk very much about our experiences, how we felt about things. It was a private place where we could be ourselves.

Remember, things were much, much harder for women in those days. Women were expected to get married. They didn’t have equal pay, there was no sex discrimination act in force, there was no rape in marriage. Husbands could chastise their wives. We now have battered women legislation but it wasn’t there then. Women were not expected to take the lead in anything and they were not expected to have careers, and the lesbians who had children would lose their children immediately if they were seen on a gay march because that would be used against them by the courts.

How did you both come into activism and how did it connect with discovering your sexuality?

Stuart: Well I guess I’d been having sex with classmates at school from the age of about 13 or 14 – I can’t quite remember – but by 15 the penny dropped that I was one of them and that was a big shock at first. By 16 I had a regular boyfriend. He was 19 and he knew stuff about the Wolfenden report coming out. We arranged to go to different newsagents to buy the newspapers and we would go through them together at lunchtime to look at who was pro and who was anti in the newspapers. When I was 18 I left home and we got two separate bedsits in a house in Huddersfield and there was a big gay community there.

I’ve always had my bold moments. I remember, it was 1961, I had friends in South London and for some reason they said, ‘We’re going to this dance, would you like to come?’ And it was a straight dance. This boyfriend of mine was sort of doing little steps in the corner and I said, ‘Let’s just dance,’ so we did, and there was a sort of electric moment where people were startled, but within five minutes everybody was beaming and it all seemed perfectly natural. So that was a bit of an eye-opener for me.

Nettie: I was somebody who was attracted to men and totally failed as a heterosexual – never had a boyfriend and I was looking for a liberation movement. Then my best friend turned out to be gay and we went to a gay liberation meeting. I never looked back after that – I got very deeply involved in gay liberation, and then I found I was attracted to women. It was such a wonderful atmosphere – the things we did together, the fun we had.

It wasn’t all serious. People tend to think of pioneers being very serious and brave. It was in a way, but it was also about having great fun. After the gay Pride march [in 1972] we all went to Hyde Park and played silly games and shared food and took drugs, because recreational drugs were very much part of the culture of the GLF – mainly cannabis but also LSD. Quite a proportion of people who were involved in GLF also took those drugs. It’s something that brought us together. Family’s not quite the right word, but there was a connection with people we hadn’t known a year before. Suddenly they were part of us and we were part of them.

That first march in 1972 was very heavily policed – what was that like?

Nettie: Yes! There was almost more police than marchers – it was extraordinary, and they all looked very grim as well, like, ‘Do we really have to do this?’

Stuart: Disdainful, they were. They were looking down their noses and sneering, mainly. [GLF member] Andrew Lumsden found a policeman who gave him a long, sly wink – in fact, in those days there were lots and lots of gay policemen because it was a safe. No one would ever dream that a policeman could be gay. Police were so respected in those days – everyone believed that what they said was true.

Nettie: There were also policewomen – that was of great attraction to lesbians because it was a way of mixing with other women.

Was there any sense of fear or trepidation going into that first Pride march knowing that it was going to be so heavily policed?

Nettie: Well I was very used to going on demonstrations – I’d been on Vietnam demonstrations and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and others, so no, I wasn’t the least bit worried. Certainly being with all my comrades on this march, I didn’t feel the least bit nervous. I think the people who did feel nervous may have felt so because they weren’t out and this was a big coming out, but I had already done that.

It sounds like a time of really rich activism with different movements ready to come together and show solidarity. Could we do with more of that today?

Nettie: I think there’s a split in a sense. We’ve got commercial Pride, the one on Saturday (2 July)… It’s not connected with liberation, nor are all of the floats, which are not very ecological to start with but advertising Barclays and Tesco – it really has become a parade and not necessarily a good parade. We wish well to all the people that go on it, the ordinary marchers. For some of those it’ll be the first time they’ve come out. But there is something drastically wrong with the movement, which is why the GLF is going to have its own demonstration which will be a protest.

Stuart: I think it’s rather difficult to get unity until we have a common political basis for understanding our position in society and that’s just not available at the moment. We are a socialist movement. The GLF right from the beginning was founded on socialism, on the idea of changing society, because we said, it’s not us who’s going to change, it’s society that’s going to change. I think that is the great block of misunderstanding on the part of some groups [today], and I don’t think intersectionality will work until we have a common basis for talking about our differences.

Nettie: Things have changed radically in the last 10 years. I think the movement got pretty complacent. People were saying things like, ‘Well we’ve got gay marriage and anti-discrimination laws, we don’t really need to exist anymore.’ But some of us were saying, ‘Yes, but for how long?’ It doesn’t mean we mightn’t be more oppressed again in the future, and I think we can see the way things are going. There are terrible things happening around the world with Roe v Wade and the issue of conversion therapy, which the government pretends they’re going to outlaw for lesbians and gays but which they’ll refuse to outlaw for trans people. We’ll have to see if they actually do anything – I don’t think they’re going to do anything for anybody. They’re just targeting trans people because they’re not as popular as the “respectable” lesbians and gays.

Nettie Pollard, Stuart Feather and others who took part in the first ever Pride march in 1972 will be taking to the streets of London to retrace that original route on Friday 1 July. All are welcome.