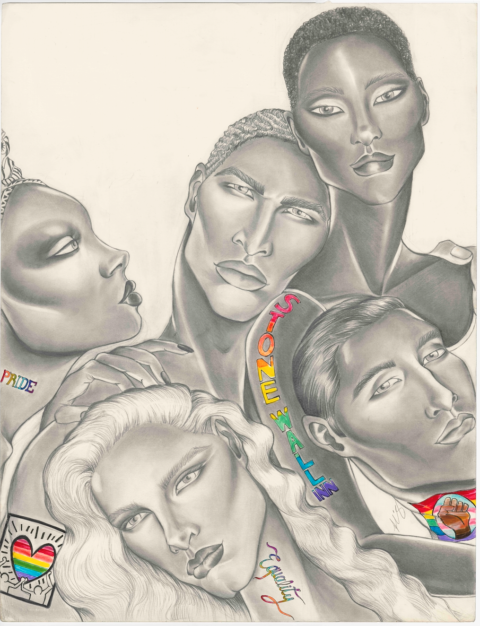

Connie Fleming’s Exhibition is About Embracing Universal Beauty

Montreal’s Never Apart art gallery features the illustrations of New York City’s favourite nightlife icon.

The pandemic has been tough — I understand that this is not a hot take. Heightened anxieties, isolation and very real tragedies have made the last 18 months especially bleak. Turning away from all of that to instead appreciate and radiate beauty is a tremendously difficult feat, but it is exactly what Connie Fleming has accomplished with her latest project, an artwork exhibition titled Ink.

While she is most well known for her work on the runway as a model in the ‘90s and early 2000s, Connie began drawing at a young age, “Being a trans kid was super hard, it was violent both verbally and physically. But drawing was something I was rewarded for and it gave me hope for the future,” she explained.

The exhibition is featured at Never Apart’s art gallery in Montreal and will be on display until December 18. Those unable to travel to Montreal can tour the gallery virtually on Never Apart’s website.

Never Apart is a non-profit organization that aims to educate folks on equality and social movements by highlighting art and music from a diverse group of artists.

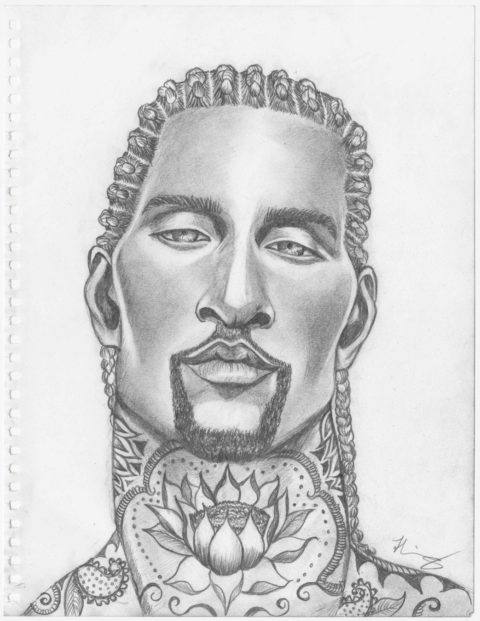

Inspired by the work of Antonio Lopez, George Stavrinos and George Petty, among others, Connie has drawn a variety of black and white portraits and figures for this collection. Some subjects are featured with their natural hair, others with durags and nearly all of them are heavily tattooed.

“Hopefully this is part of the progression of society,” she said, “now that the beauty of African features and hair is really being seen and not just pawned off immediately as unprofessional or ugly.”

When did you first begin illustrating?

It was always a part of my life. I remember even before first grade I was always drawing. When I was little in Jamaica my mom was a teaching assistant and when I was two or three she taught me how to write my name and my numbers and I was obsessed. I always had a pencil in my hand, I was always doodling and drawing. Illustration has remained [into adulthood] my solace, and is a safe space for me.

What was it like making art during the pandemic?

It really saved me from going crazy. It saved me from falling into TikTok and Youtube rabbit holes. I had already seen everything on Netflix and I just felt an atrophy in my body and my mind. I needed to get out and do something.

How did the pandemic inspire this exhibition?

A really good friend passed during the pandemic, Nashom Wooden aka Mona Foot, and then I had another friend who passed as well, and between that and the daily COVID death tolls it was really dragging down my spirit. I felt really drained by the idea of connecting through death and I wanted to contribute some beauty to the world. So I started to post my art online and I got a really great response. I was like, “Let me just keep putting out some beauty and life into the world,” and that became the direction. I never expected it to turn into anything.

Why did you choose to use a mostly black and white colour palette for these illustrations?

I wanted to get that tonal richness that you can get from black and white. Like film noir, that sort of quality. I also really wanted to get the depth of African American skin without using colour, to show how light played off black skin.

I notice that many of the subjects in your pieces have tattoos, what was the inspiration behind that?

With the political atmosphere with George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement I was seeing Black bodies being criminalized and I wanted to show the beauty instead. I wanted to show that tattoos aren’t about being a thug or a criminal, but that it’s about expression. It’s almost like you get to be your own personal billboard.

But I also wanted to honour the history of tattooing because it connects us all in a way. Today we may be immersed in technology with our phones always in our hands but we still need human connection. To begin with tattoos were symbolism, whether it was your tribe, or religion or a rite of passage, it was a symbol that we were all part of humanity. I think these aesthetic expressions are important.

What would you say you are most proud of from this entire process?

Two things, first is highlighting the beauty of African and Black features and second is pushing myself as an artist and really honing my craft. I want to pat myself on the back, I learned that I have the ability to create and mold, a little like some of my heroes — but don’t tell anybody I ever said that!