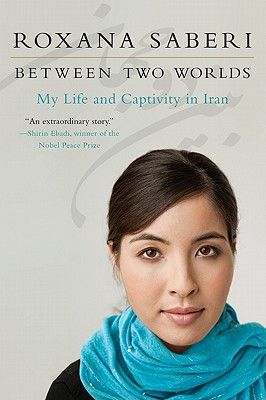

‘I Left Behind a Country Full of Dreams and Uncertainty’: Roxana Saberi on Her Week in Kabul

Agnes Reau, CBS News producer

Just three days before Kabul fell to Taliban forces, CBS News foreign correspondent Roxana Saberi entered the Afghan capital to report on the militant group’s takeover. It was a swift transition and the end of the United States’ costly 20-year war in Afghanistan. Saberi and her team spent the next several days filing stories from the ground, talking to Afghans who were desperate to leave the country and terrified of a future under Taliban rule. (The last time the Taliban was in power from 1996 to 2001, the group was brutal and violent and denied women the right to work, attend school, or travel without a male chaperone.)

“It was heartbreaking to feel the suffering of the Afghan people firsthand,” Saberi tells ELLE.com exclusively via email. The London-based reporter joined CBS News in Jan. 2018 and previously covered Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban in the early 2000s. The CBS team was able to leave Kabul on Wednesday, Aug. 18, airlifted out by U.S. troops, along with hundreds of Afghans. “I left behind a country full of dreams and uncertainty,” Saberi says.

Below, Saberi discusses what it was like to be reporting during the chaos; what she’s heard from the Afghan people, including those who were and weren’t able to get out; and the questions she’s seeking to answer in the coming months.

While in Kabul, what kinds of stories were you trying to tell, and what was the hardest part about doing so?

Stories that show the timeless and universal themes of the longing for peace, the cost of war, bravery, hope, and love of family and country. I’ve been moved by the warmth and resilience of the Afghan people, who have been through so much in such a short time. I’ve also wanted to show the very real impacts that U.S. policies—both America’s presence in Afghanistan and the decision to withdraw all American troops—have had on Afghans’ lives. Many Afghans are too young to remember Taliban rule, and they feared losing certain basic freedoms, including education for girls, that many of us often take for granted.

The hardest part was the difficulty of interviewing and moving around in Kabul after the Taliban arrived, as well leaving the country, knowing that many Afghans are facing such an uncertain future.

What were the challenges or limitations of reporting from Kabul? With the Taliban taking over, did you face any extra limitations because you’re a woman?

As a journalist, I’ve found that many Afghans wanted to speak with us to share their stories with the world. But after the Taliban took over last weekend, some are clearly more fearful of Taliban reprisals. For example, two people asked us to blur their faces when we interviewed them. They told us they went into hiding.

Before the Taliban arrived in Kabul, we filmed in the streets cautiously but relatively easily. After they came to town, our movements and ability to shoot became much more limited. Many Afghan journalists were harassed, targeted, and killed by the Taliban in the past, and though the Taliban held an official press conference earlier this week, we have seen reports of their fighters already starting to harass journalists.

I found that as a woman journalist, some Afghan women seemed more comfortable speaking with me than if I were a man. It also helps that I can speak and understand Dari fairly well because it’s similar to Persian, and I lived and worked in Iran for six years.

What have you heard from Afghan women and girls about their fears or hopes for their future?

They all told me they want to be able to continue going to school and to work. Two little girls wounded in Taliban attacks told me they wanted be doctors. Pashtana Durrani, the founder of LEARN Afghanistan, a charity focused on education, told me while the Taliban are now pledging to respect women’s rights, that will be according to their strict interpretation of Islamic law. She went into hiding after the Taliban captured her city of Kandahar. “Would they let them study technology, engineering, mathematics?” she said to me. “What about political rights of women? What about the educational rights of women? Women want to contribute into making Afghanistan stable. But where do they stand? Do they become pawns in the game that is played by the two warring parties? That makes me worried about them.”

You said in one of your reports that an Afghan man called your team in the middle of the night terrified. Can you explain more about what happened?

He told us he went into hiding after the Taliban kidnapped two of his colleagues just in the past few days. They all used to work for the now-former Afghan government. I have heard other accounts of Taliban fighters knocking on people’s doors since they seized Kabul. One said they did a sweep of her relatives’ home, found nothing, and left.

This content is imported from Twitter. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

What questions will you be looking to answer about the situation in Afghanistan over the next week, the next month, and the next year?

How are the lives of everyday Afghans impacted by renewed Taliban rule? Will the Taliban live up to their pledges of ruling with a gentler hand? How will the international community respond? What will happen to the young Afghans I met? What can be done to help them?

What was the most illuminating or impactful interview you conducted while in Kabul?

There were quite a few, but I was most moved by the Afghans I met on a U.S. military plane leaving the country. I joined hundreds of Afghan men, women, and children evacuated by the U.S. Sayed Jalal-Zaheer told me he was able to get U.S. visas for himself and his family because he had worked as a translator for the U.S. military. He said if he had stayed, the Taliban would have killed him. He was relieved to be leaving, but he feared for the friends and relatives he was leaving behind. When I asked what his hopes were for his children’s future, he said he hopes they’ll have a bright future, wherever they are, and that they’ll see Afghanistan again—but at peace.

This content is imported from Twitter. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

I was also touched by Sharifa, an eight-year-old girl who lost her leg in a Taliban attack on her village a few months ago. I met her at a hospital where she was learning how to walk with a prosthetic leg. When I asked what she was afraid of, she said, “Not being allowed back to school.” Her smile was beautiful.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io