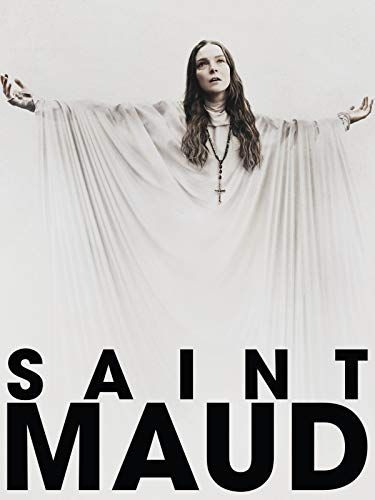

Saint Maud Examines a Crisis of Faith Through Unmitigated Horror

Like so many of us watching the world burn, writer-director Rose Glass has wrestled with her faith. She grew up attending Catholic schools in the U.K. and has vicars in her family, so the thought of questioning her Christianity stayed dormant for years. But now, on the cusp of her unsettling debut film, Saint Maud, she reflects on what she didn’t articulate back then: “It’s like, who’s calling me?”

Enter the titular Maud, née Katie (Morfydd Clark), a reclusive hospice worker who’s recently reinvented her life and devoted herself to God following the shocking death of a man under her care. She turns her attention to a new patient, Amanda (Jennifer Ehle), an American dancer dying from stage four lymphoma, and becomes terrifyingly obsessed with not only providing Amanda emotional support, but saving her hedonistic soul.

While Glass says she has “quite a healthy relationship” with her faith these days, she admits that making Saint Maud stirred up residual feelings she channeled into her protagonist. “Some of the stuff you only realize in hindsight, after you’ve made it,” she says of the filmmaking process. Using the heightened landscape of the horror genre to explore how far a “very zealous, religious character” can go, the filmmaker also examines resonating themes of isolation, shame, and unbridled fear that Maud feels—and projects—as a woman of faith. As Saint Maud spirals toward a petrifying finish, it makes you speculate, as Glass has, what the true path to salvation really is. “It’s dangerous to constantly be seeking external validation instead of just being happy with yourself,” the director ultimately concludes.

Here, the filmmaker discusses forging her own relationship with religion, using horror to examine grave themes “dressed up in fun,” and the personal woes that plague both the faithful and the faithless.

Is the story of Saint Maud a personal one in that it deals with a crisis of faith?

Not in an autobiographical sense. It didn’t stem from a crisis of faith I’d had in particular. It’s all fairly abstract connections. You always end up filtering whatever weird personal stuff you’ve got going on into it somehow, but I think I sort of hid away from [that]. It’s a character that I resonate with, I guess.

What were some of those things you might have filtered into the film?

The religion stuff, because Christianity was so familiar to me growing up. It was quite a big presence, but it was never rammed down my throat. I just didn’t question it a lot growing up, as probably a lot of people don’t, and then got interested in it from a slightly more outsider perspective later on. I feel like I’ve got quite a healthy relationship with Christianity in that it’s not too close.

I was also raised Christian and experienced questions of faith, particularly how a lack of faith can have grave consequences. Saint Maud reflects a quite violent form of punishment for those whose faith is wavering. Maud punishes herself, then her heathen employer.

Well, I guess in Christianity, almost the worst thing you can do is not believe. But the whole thing of faith is believing in something without evidence, which I’ve struggled with. I was interested in the role faith could play in someone’s life, even someone who objectively says, “I’m not a particularly spiritual or religious person.” But weirdly, through the process of making this film and writing this story, I was tapping into feelings and thoughts within myself, which maybe are the same things somebody who does have faith or is going through a crisis like Maud might.

The violence, and the sort of flagellation stuff, all that’s kind of quite neatly baked into a lot of Christian history. Well, not even just Christian—probably a lot of forms of organized religion: pain and penance and suffering as a way to godliness. That fed into Maud’s own sense of self-loathing and guilt and shame pretty neatly.

It’s why I’ve always thought horror was an apt genre to discuss these questions of faith. Did you always know it would be a horror movie?

In the beginning, I didn’t. I’m not too fussed about the genre question anymore. We had a lot of discussions about that whilst developing it, but I don’t think I consciously thought of it as a horror film. But I always knew that it would be heightened and stylized and not super naturalistic, or maybe even realistic. One of my producers, when he first read the treatment I put together, said, “Oh, this feels like a horror film.” I kind of went, “Okay.” [It] didn’t change how I was thinking about it too much. Maybe he encouraged me to lean into some of those elements a bit more. For me, it’s not necessary specifically horror. I like stories where you can hide more subtle things in something dressed up in fun. In horror, you’ve got a big toolkit to play with the fun elements, and [it] lends itself well to visually experimenting and surrealism. You can mask what you’re saying more; it’s just a fun silly ride we’re all going through.

Your decision to make Maud a nurse is so intriguing because nurses and pious people are both revered as healers. Can you talk about that?

I knew I wanted this very zealous, religious character in a contemporary setting. It’s a glib way of saying, I guess, that the closest profession I could think of akin to a saintly figure in a contemporary setting was nurses and medical staff. It made sense to me that Maud would be drawn to that profession. Also, because she’s somebody who’s always found it very difficult to connect with people emotionally and socially, bodies seem less ambiguous to her. Physically caring for somebody is like, “I know how to do this. Bodies work a certain way. I can do it.” It’s the more emotional, psychological stuff that she struggles with.

It seems like Maud’s inability to connect with people is almost intentional, a way of shutting herself off from people and her former life. She certainly does that with her former colleague.

Oh, definitely. Some of my favorite scenes are her trying to chat to normal people. I figured since finding God and taking on the name Maud, she’s becoming a happy person. Her faith in this new identity she’s kind of created for herself helps her keep herself together and feel a bit better than everyone else. Sort of, I don’t need you guys anyway. Which I find hilarious in some scenes and very sad in others.

To Maud, Amanda is quite exotic in the context of the country she’s living in. Suddenly there’s this sort of cool, mysterious, slightly famous artsy type who seems to be interested in her, who seems interested in the fact that she has faith rather than taking the piss out of her—which I imagine is probably what she gets most of the time. There are moments later in the film where we get a glimpse into what she was like before she found God, when she goes out to the pub and stuff. You get to see how she struggled before, that awful feeling of trying to be casual and meet new people and connect, and it just being this torturous, torturous experience. I’m sure a lot of people can relate to [it] on some level.

After being unable to connect with people in that bar scene, she goes home with a guy—and he rapes her. Why did you decide to include that scene, which also includes a callback to Maud’s medical mishap?

I guess it’s a strange scene to talk about. It starts off as a sex scene and then she has this quite traumatic flashback. After that, it’s a rape scene. And I think the switch…sometimes gets missed. Even some people who were working on the film, [when I] mentioned the rape scene, they’re like, “The what scene?” That whole night and the scenes leading up to that moment, the intention at that point [is that] she’s had her holy mission to save Amanda pulled out from under her feet. It felt like a smack in the face for all the hard work she’s been trying to do. She gets nothing for it. She’s back to square one.

In my head, that’s her sort of Jesus-wandering-the-desert-wilderness and questioning her faith phase. Like, “Fuck you, God.” For me, it was important for people to realize what her life is like without faith and behind this strange veneer she’s created for herself. It’s someone who’s flailing and in desperate need of interaction and communication and support but doesn’t know how to go about asking for it and ends up slipping back into self-destructive patterns.

With the rape scene particularly, I know that’s a trope in some rape-revenge things, of the woman [who] has to be raped before she can be empowered. I felt like it was important to show the danger she’s in, the state of mind she’s in, and have that lack of awareness of her situation. She doesn’t have the ability just to make it. She tries, he ignores her, so there’s nothing more she can do there. It shows how vulnerable she is, how easy it is for stuff like that to happen. Me and Morfydd talked about it. In my head it’s probably not the first time something like that might have happened to her, and I don’t think even in Maud’s head she would consciously consider what happens in that scene a rape. It was an important element of that scene. But I didn’t want it to be, “This happens and then that’s the trigger for everything that happens next.” Because it’s not. It’s part of it, but not everything.

When God finally speaks in the film, He sounds demonic. I thought for a moment that He might actually be the devil and killing Amanda is how Maud becomes sanctified in His eyes. Is it possible the only devil is the one she’s worshipping?

Possibly. I mean, maybe this helps: that’s Morfydd’s voice that we just sort of pitched down.

Oh!

It’s got to be Welsh because Morfydd is Welsh. That scene wasn’t originally in the shooting script going in—I sort of wrote it during the edit and added it in because it felt that there was a bit missing and we needed God to give her a final push. So, I was like, okay, God has to appear and speak. We decided it would be the cockroach. Then I’d listened to Morfydd speaking Welsh on the phone to her sister during the shoot, so I got a bit more familiar with how it sounded and was like, “Ah, lovely, mysterious language no one will recognize.” Which is great. So, it’s her—to me, anyway. Obviously, people won’t know that watching the film unless they’re told. But I do like that it could go either way. I welcome any and all interpretations. [Chuckles]

Yeah, I don’t know what I’m bringing to it. But that’s how I saw it.

We wanted everything to be from a very objective outsider point of view. Yes, probably a lot of what happens in the film on a literal level is a result of psychosis and delusions. But the experience Maud’s going through, even if that’s just sort of the scientific explanation for it, doesn’t give you much insight into what she’s actually experiencing and why she’s doing stuff. So, yes, she could have been accidentally led down the path by a dark force, because obviously, the God most Christians pray to probably wouldn’t tell her to kill Amanda.

Exactly. That brings me to Saint Maud’s final scene, the fiery crucifixion. Is her descent inevitable? Could she ever truly have been saved?

Yes, absolutely. That was sort of too little, too late by that point. But that was the idea with the nurse, Joy, coming to her bedsit towards the end to check on her. Maud tries phoning her early in the film and for whatever reason, that person couldn’t talk, so she checks in a bit later, but by that point, Maud’s already put her guard up again. The one time she does reach out for help—during that night before she goes home with the bloke and gets raped—she does reach out to the friend and [is] rebuffed. But I think, even if just that night, somebody had sat down and had a proper chat with her and she’d actually let down her guard and let them know what’s going on, I think things could work out a lot differently.

It could literally be the difference of a conversation—getting somebody to realize the situation they’re actually in. Sometimes, when you’re so far gone in your own head, it all happens very, very incrementally and gradually, and you don’t realize it’s happening until someone else points it out. She’s obviously pushed it to an awful extreme. But I still feel the intention was that everything she does is motivated by quite universal stuff: the constant thing of striving to be good and perfect and good at what you do, and feel validated and like you have a purpose for being here—that you contribute something, that people notice and respect you. It doesn’t necessarily have to have anything to do with religion or flagellation stuff. Obviously, that’s where a lot of these things get channeled.

Human beings, I think, are quite good at punishing ourselves and thinking, Oh, if I just do this, if I just do that, I’ll make it better next time. It’s dangerous to constantly be seeking external validation instead of ultimately just being happy with yourself—which is obviously easier said than done. In Maud’s case, it’s done in a deliberately provocative way, but I think even in much smaller examples, succumbing too totally to any external force or power is quite dangerous.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io