Farewell to ‘Evil,’ a Show That Will Leave Us Knowing It Was Right

In the Christian world, faith is often a matter of endings—of knowing what to anticipate from them, even if the believer can’t possibly know when theirs will arrive.

On Evil, the end is finally here, and none of its characters are taking it very well. The unlikely Paramount+ cult hit about a team of “assessors” hired by the Catholic Church to investigate alleged instances of supernatural happenings ended on Thursday with an open-ended sense of closure. Across four bonus episodes appended to the current (and, for now, final) season, Evil tidied up unfinished business following Paramount’s decision not to move forward with a fifth season. Creators Robert and Michelle King are trying to get the show picked up by another network, but until that happens—if it ever does—Evil will remain suspended in limbo. Those last four episodes were written with knowledge of the show’s fate, and they serve as a coda for what will be remembered as one of the great series of its era.

The Kings, the husband-and-wife duo behind Evil and other boundary-pushing broadcast dramas such as The Good Wife, were not terribly subtle about their goodbye. In the tradition of shows like Battlestar Galactica, which contemplated its end with a final plot about the eponymous spaceship falling apart, Evil begins its last bow with its three protagonists losing their jobs: The archdiocese has determined there are more cost-effective ways to investigate potential occurrences of the demonic or divine and ways to more effectively ascertain whether the church’s involvement is warranted.

Even the Catholic Church, it turns out, is subject to the whims of capitalism. And so Evil’s trio, comprising newly anointed priest David Acosta (Mike Colter), tech specialist Ben Shakir (Aasif Mandvi), and forensic psychologist Kristen Bouchard (Katja Herbers), must now figure out what comes next, even as possible demonic forces conspire against them.

The ensuing episodes are a virtuoso display of everything Evil did best: a nonchalant blend of sturdy procedural casework, casually profound discussions of virtue or malevolence, off-kilter humor, and B-movie horror. Mostly, though, the episodes felt angry. Of course they felt angry. The work was not done.

Like a lot of people in a moment of personal crisis, David, Ben, and Kristen respond to news of their unemployment by spending too much time on the internet. Late at night, Ben and Kristen visit a website that scans the user’s face and matches them with their doppelgänger—someone somewhere else in the world that looks just like you. Someone that could be you, maybe, if your circumstances were entirely different. David, the stoic priest, whom Kristen uploads a photo for on his behalf, is matched with a fitspo influencer, who hits punching bags and tells his followers how to stay motivated and channel their emotions. Ben, the perennially single rationalist, is matched with a family man, the picture of normie domestic bliss. And Kristen, the furious heart of the show—abandoned by a useless husband, fierce protector of four girls and an infant that might be the Antichrist, lover of canned margaritas—discovers her doppelgänger to be a free-spirited Dutch singer-songwriter, with not a care in the world.

Illuminated by the glow of their screens, Kristen and Ben contemplate their doppelgängers, pondering what path the trio might have taken if they didn’t have all these nagging questions itching in their brains. Questions are what Evil built its identity on. Under the familiar procedural structure, which the Kings frequently subverted, the show found strange, goofy, and at times harrowing ways to engage in never-ending philosophical debate.

It could be aggravating how comfortable a given Evil episode was with uncertainty, obsessed with questions. Can the unexplained always be solved? Does faith have a place in rational society? Evil argues that there is no right answer; only skepticism in believing you’ve found one. In every episode of Evil, its central trio would investigate a case of the supernatural, and regardless of the outcome, it would always cause the characters to shuffle uncomfortably in their archetypal positions: man of faith, man of science, woman in between.

The angst Evil’s team of assessors feels at the end of the show is a reflection of the sentiment that kicked off the series. Our world, it seems, is just getting worse. Bad people are finding each other on the internet and using their newfound connections to drag everyone down with them. The Kings, masters of the broadcast TV drama, worked with their writing staff to plumb headlines for their modern morality plays, often cheekily drawing a red line between the tech industry and the demonic. An AI chatbot built for the grief-stricken to talk to their lost loved ones appears to be hijacked by an evil spirit; a Neuralink-style brain implant might be possessing a renowned (and misogynistic) theoretical physicist; virtual reality software frequently appeared, never for anything good.

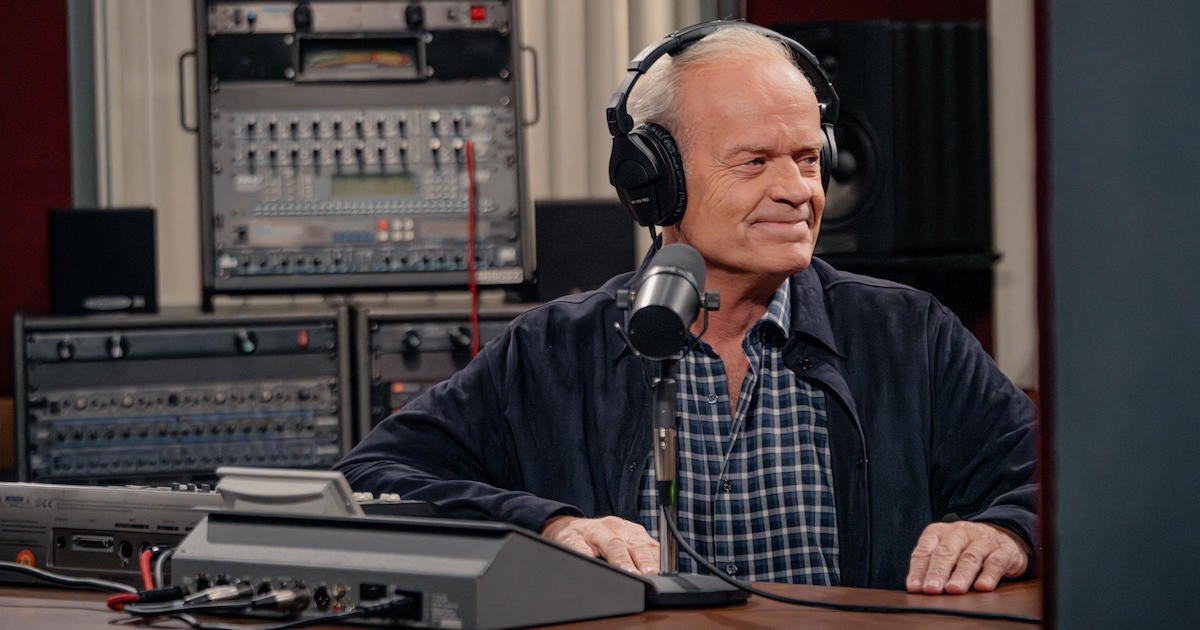

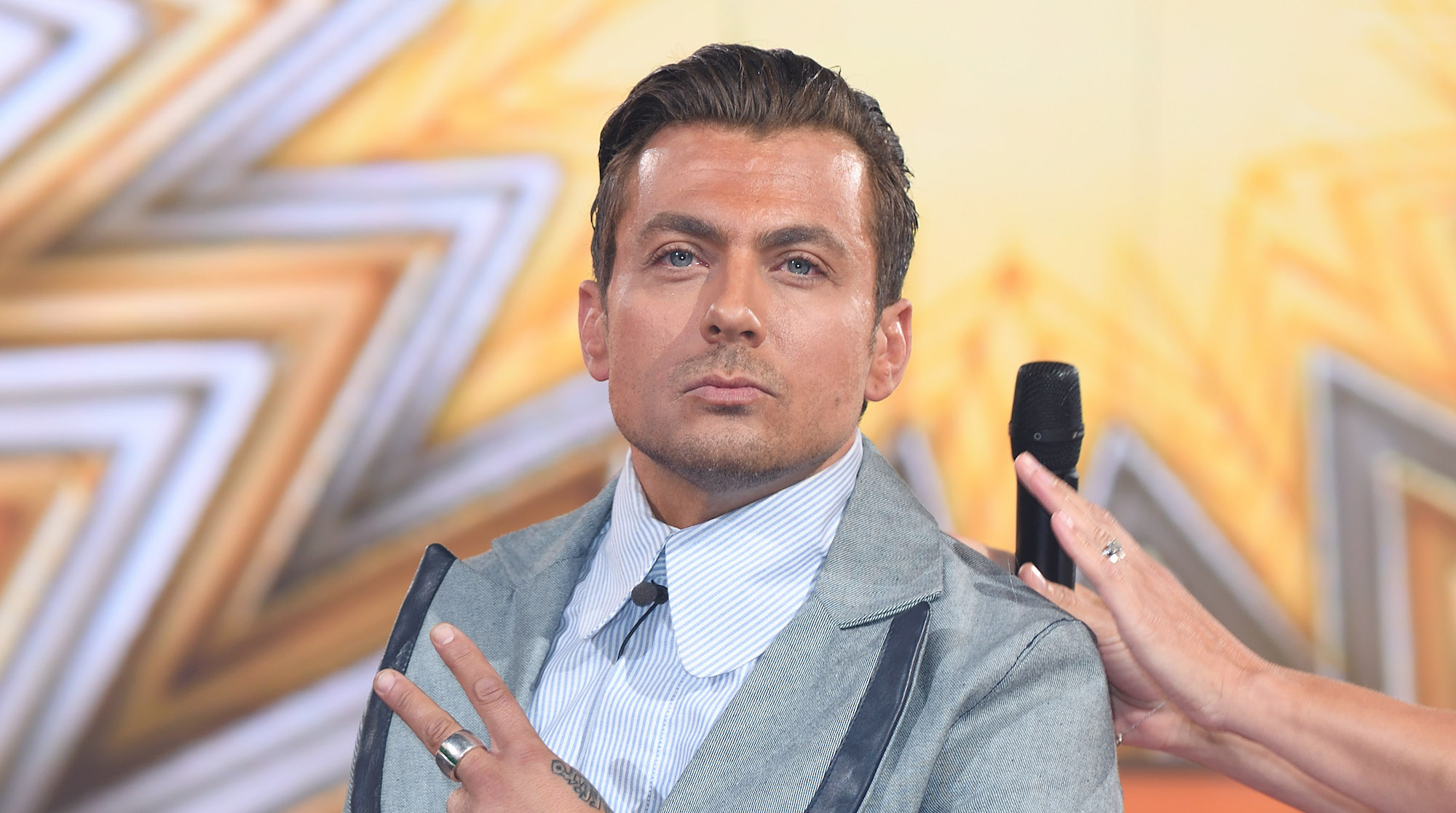

Yet episodes that played coy with the existence of the supernatural were complicated by others that featured actual demons who disguised themselves in human skin or employed people to work on their behalf, like the show’s fourth major player, the antagonist Leland Townsend (a sublime Michael Emerson). As the assessors try to ascertain on a case-by-case basis whether there is a supernatural root to the evil in the world, Leland, a professional rival of Kristen’s, is a pesky prairie dog continually surfacing to assert that there absolutely is such evil and that he is its loyal servant.

Even considering the casual appearance of infernal demons and the name of the show itself, Evil was never interested in a rote struggle between the eponymous abstraction and its opposite. Leland, for all his efforts to corrupt our heroes and bring forth the Antichrist, was never really a foe to vanquish so much as he was a meddler, muddying the waters until he was the only thing visible in them.

This dovetails with the final season’s loose thematic focus on scientific thinking, and how much uncertainty comes with the pursuit of knowledge. In this, the series’ writers lean into one of the terrible truths at the heart of the modern world: how hard it is to truly know anything. When digital avatars can be fashioned in our image without our consent, artificial intelligence can mirror human prejudices, and consumer electronics can place us under constant digital surveillance—forming takeaways that are not always accurate—empirical truth becomes harder than ever to find. Our perception of the world is so thoroughly mediated it might as well be branded.

To its credit, Evil never shied away from the fact that it was so damned Catholic. The irony of the fact that the assessor program was a semi-secular Justice League that worked for the church was never lost on the show’s writers, who frequently had Kristen and other characters make jabs at the abuse scandals, the patriarchal power structure, and the institution’s long history of denying the legitimacy of mental health, instead assigning responsibility for psychological ills to the demonic.

Like the justice systems on other Kings shows such as The Good Wife and The Good Fight, institutions are frequently fallible and at times barely redeemable. But in the Kings’ moral universe, divorcing yourself from a corrupt institution won’t necessarily bring you any closer to the truth.

Our world is mediated, remember? The truth is often obscured with algorithms and search engine optimization, giving us what we want to hear. How can we know that what we’re doing isn’t fueling some terrible movement? That the good work we are in fact doing isn’t for naught? Evil responded by never valorizing moral certainty. Its core trio perpetually wrestled with doubt; their motivation was never to convince the others their perspective was the right one. Was a terrible plane malfunction they were enduring the result of a cursed artifact on board, as David believed? Maybe. Or maybe Ben was right, and it was a mere coincidence. Evil was never concerned with something as mundane as its heroes being right—what mattered was that they kept each other open to being wrong.

More than anything, Evil loved questions, and answers that pulled the rug out from under long-standing certitudes. In the show’s first episode, Kristen calls it “killing Santa” when Ben uses his technical expertise to inform a client that she is not hearing an otherworldly presence in her house, but rather a malfunctioning appliance. The pair have a conversation about the perverse anger people feel when discovering a rational explanation for something they believed was supernatural because people would sometimes rather believe in ghosts or demons.

Across four seasons and 50 episodes, Evil remained compelling by never making the rational explanation the easier one to believe, nor the supernatural evil a convenient malady. It was a show built to last forever, because of both its old-school trappings and its open-minded, never-ending commitment to the wry exploration of our biggest questions. Circumstance has left the series with only a conclusion of sorts, but true finality isn’t really in the show’s DNA. Evil isn’t something the show ever posited could be vanquished—it was something to probe, to expose, to travail against by always looking for the truth.

Joshua Rivera is a Philadelphia-based culture writer whose work has appeared in GQ, New York, Vanity Fair, Polygon, and others. You can follow him at @jmrivera02.