A Case for All Points of View

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

There’s a strange complaint that I’ve seen occasionally in bookish circles. The complaint is that someone doesn’t like certain points of view in a novel. By point of view (POV), I’m talking about the voice of the narrator in a book. There’s first person, where you’re fully in the head of the protagonist, who is talking directly to you using the pronoun “I.” There’s third person, where the narrator is disembodied and observing the story. Everyone is referred to by name or their gendered pronoun like he, she, they, or xey. And there’s the rare second person, which uses the “You” pronoun, as though you, the reader, are part of the story. I have a hard time thinking of second-person examples beyond the old Choose Your Own Adventure books.

The complaint, then is, that a reader only likes first-person or third-person POV (second-person doesn’t come into the conversation much since it’s pretty rarely used). I was confused to hear that anyone could have this opinion, particularly since my MFA education started screaming at me.

So, what’s wrong with having a preferred POV for novels? It might be limiting what you understand of an author’s intent in writing a story. Part of being a great author is recognizing that not every point of view works for every story. It also overlooks that there are more than just three points of view available. The POVs can and are dynamic.

So Many Questions

Let’s start with the first and easier case to make, which is that every story needs to factor in the correct POV to tell it well. When thinking about a story and how it needs to be told, there are a lot of factors to consider.

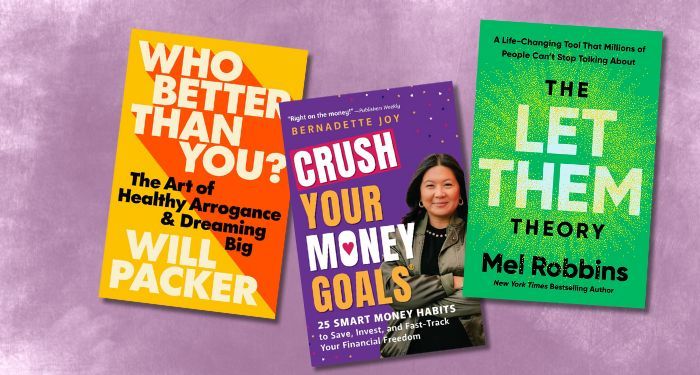

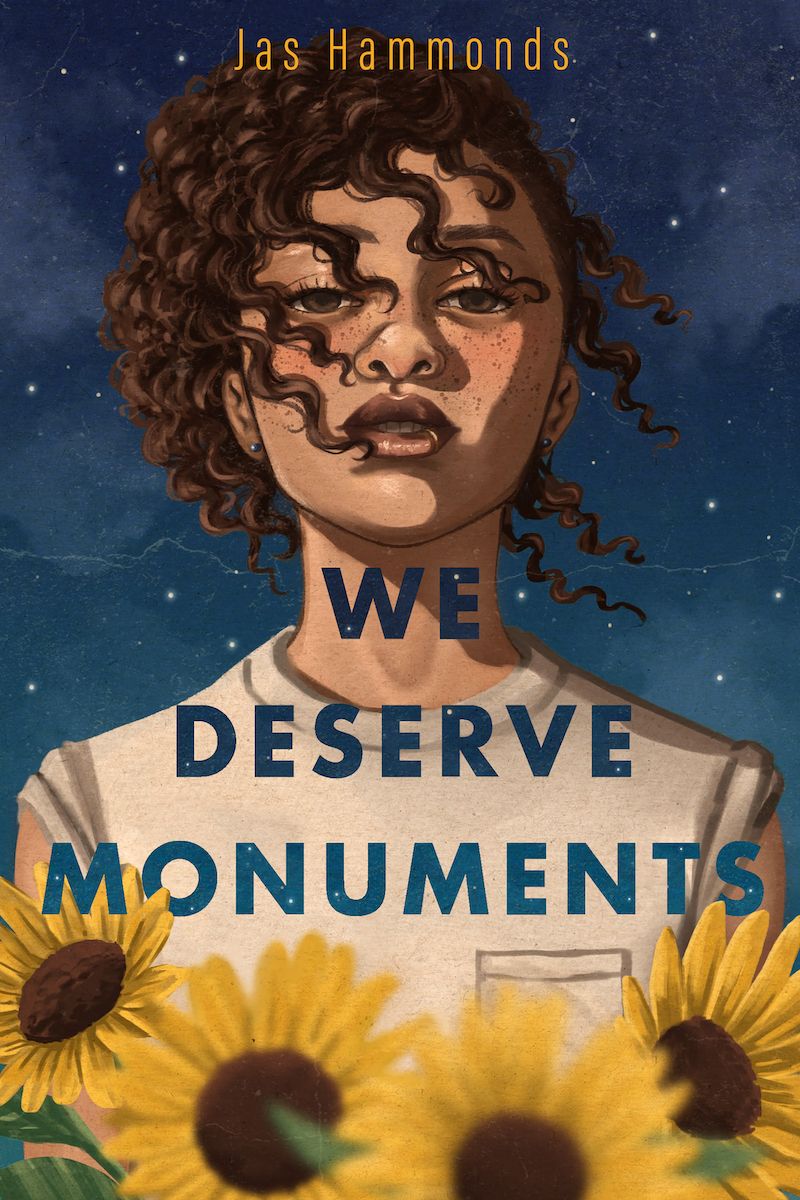

Does this story heavily rely on the interiority of the protagonist? If so, then a closer POV, like first person, could be a good choice. This is why a lot of YA is in first person; the nature of the coming-of-age story requires you to understand the interior journey of the protagonist. We Deserve Monuments by Jas Hammonds is a prime example.

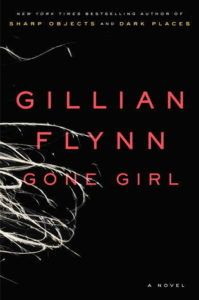

Is there a lot of external action that stands as a metaphor for the interior landscape of a character? Is there a lot of mystery or intrigue? These could be arguments for any POV, really, but have to be considered. In a mystery, the writer may not want the reader too close to the protagonist’s thoughts. These could make a good case for third-person, but then, Gone Girl shows the power of an unreliable first-person narrator.

Does the story span lots of geographical area or a long timeline? This could be a good argument for the third-person narrative. Looking at you, A Song of Ice and Fire, which spans two continents and moves through several characters in each book, always in third-person. Or in Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston, the shifting POV is used to capture the myriad experiences of its characters. First-person POV doesn’t work well with multiple narrators, after all. Not impossible, but it is extra challenging.

The Bird of Psychic Distance

The third-person POV brings an extra wrinkle to this conversation. I address this wrinkle through a metaphorical bird.

Imagine third-person POV as a spectrum based on the distance between the protagonist(s) and a bird. That bird is our narrative voice. The bird might be flying high, very high overhead. That bird is observing the actions of everyone, making no judgments on anyone, and has no idea what anyone is thinking beyond external clues like facial expressions.

Now, imagine that bird sitting on one character’s shoulder. Better yet, imagine that bird tattooed upon the heart of the protagonist. While still in third-person POV, every emotion of the protagonist is described. We, the reader, know what the character is thinking and feeling for the most part, though the protagonist is not directly speaking to us.

And that bird can be anywhere in between. It all depends on the psychic distance required for the narrative. If a story is particularly brutal, for instance, we don’t want to be in the head or heart of the protagonist. It’s too hard, too close, and can turn us off. In romance, though, we want to get in there, to feel the ebb and flow of love and lust.

What Does This Mean for Me?

“Okay, Chris. You’ve gone a bit deep into the writer weeds.”

I hear you. How does this all affect you, the reader? Particularly, the reader who thinks certain POVs can get a bit dodgy? I encourage you to please, please keep reading that story.

As I said before, certain genres like YA or mystery or romance are almost automatic in the selection of POV. If you mostly read in one of those genres and switch it up, this can definitely throw you off as a reader. So, I invite you to settle in and get used to it. I’ve had experiences myself of reading one POV for a while and being thrown off kilter when shifting to a different one.

I also invite you to examine why an author is choosing a particular POV for a story. That choice should clue you in on what the author thinks is most important. If it’s a first-person story, then the interior landscape of that one character is tantamount. If the POV is third-person and shifts between multiple characters, then the author wants you to keep track of the entire story as it unfolds across time and space.

So sure, everyone is entitled to have likes and dislikes, favorites and nots. But if POV is one of the literary hills you’re willing to die on, I ask you to let that one go. Open your mind to other POV options, particularly if you’re exploring different genres from your normal literary paths. Embrace the variety, especially if the author has chosen the POV well.

And yeah, they won’t always choose well. That’s a different problem — a problem that means maybe you DNF a book. Perhaps the next book will be better.