Andre Braugher Played Two of TV’s Greatest Cops. But Family Came First

In the first episode of the Nineties NBC cop drama Homicide: Life on the Street, Baltimore police detective Frank Pembleton, played by a then-obscure actor named Andre Braugher, reluctantly takes on a young partner, Tim Bayliss (Kyle Secor). Bayliss, new to homicide investigation, is eager to watch Pembleton interrogate a murder suspect, which prompts Frank to explain, “What you will be privileged to witness will not be an interrogation, but an act of salesmanship — as silver-tongued and thieving as ever moved used cars, Florida swampland, or Bibles. But what I am selling is a long prison term, to a client who has no genuine use for the product.”

Braugher had worked a little in TV and film prior to Homicide. He played Telly Savalas’s assistant in a handful of Kojak reunion movies, was a scholarly northern Black man who enlisted in the Union Army in Glory, and played the title role in the TV-movie The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson. But NBC had improbably chosen that first episode of Homicide — a deliberately odd, challenging, elliptical drama, based on a non-fiction book by future The Wire co-creator David Simon — to air after the Super Bowl in 1993. This meant that, for all intents and purposes, the silver-tongued salesman monologue was not just Bayliss’ true introduction to Pembleton, but America’s true introduction to Andre Braugher. It is a lecture delivered from a place of supreme confidence, and demands a high level of oratorical power to not play as arrogance.

And what America saw that night was not an actor in a cop show, but as silver-tongued and velvety-voiced a talker as had ever appeared on television, before or since. And what Braugher — who died this week at the much too young age of 61 — was selling was one indelible character and speech after another, to an audience who, over the next 30 years, found enormous use for the product.

He was a giant — and a startlingly versatile one, at that. For the first half of his career, he built a reputation as one of the greatest dramatic actors the small screen had ever been privileged to feature. And then for the second half, on shows like Brooklyn Nine-Nine and Men of a Certain Age, he proved that he could also be among the most hilarious performers on television. He was TV’s Shohei Ohtani, doing two specialized jobs as well as anyone in the game.

And now he’s gone.

Despite that Super Bowl launching pad, Homicide barely clung on to the status of a cult hit, lasting seven seasons largely because NBC was doing so well at the same time with Seinfeld, ER, and Friends that it could afford to carry this police show that was intentionally all talk and no action. And because of a complicated ownership situation and some music rights issues, the series has never been available on streaming. So Braugher’s work as Pembleton exists mostly in the memories of people who were there to watch it when those episodes aired.

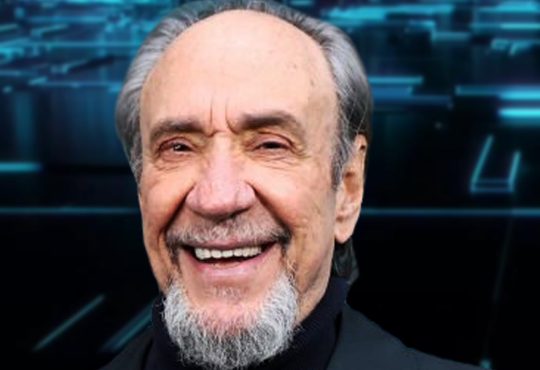

Clark Johnson as Det. Meldrick Lewis, Andre Braugher as Det. Frank Pembleton in ‘Homicide: Life on the Street.’

NBCUniversal via Getty Images

As one of those lucky few, I’m comfortable putting that performance up against Gandolfini, Cranston, Mirren, anyone. When I heard the news, I took my out-of-print Homicide DVDs off the shelf and fired up “Black and Blue,” from the show’s oddly-brief second season. (It’s the third of only four episodes, suggesting NBC’s lack of confidence after the Super Bowl bet didn’t pay off with big ratings.) The plot involves the shooting death of a drug dealer named C.C. Cox. Frank is positive that a cop did it and then tossed the weapon, while his boss, Alphonse “Gee” Giardello (Yaphet Kotto), is wary of Frank making the department look bad unless he can 100 percent prove an officer was responsible.

Frank feels frustrated with both police corruption, and betrayed by the idea that his boss and mentor — like him, a Black man working for an institution with a racist history — seems almost eager to see the killer turn out to be another Black dealer rather than a white cop. So he brings Cox’s friend Lane (played by a young Isaiah Washington) into the interrogation room — or, as it was referred to on the show, “The Box.” And over the course of 10 minutes — knowing the whole time that Gee is watching from the other side of the two-way mirror — the cop plays the suspect like Frank is a virtuoso and Lane is his fiddle.

He acts indignant when Lane reveals more information to the white Bayliss than to him. He speaks of the history of white cops beating Black suspects in the backs of paddy wagons, and suggests he has joined the police to do better by the community he and Lane share. He shows a dismayed Lane photos of his dead friend, and begins incepting into him the idea that, because Lane got C.C. into a life of crime, “You put the bullet out there.” He speaks so quickly, so seductively, and so forcefully, that by the end of the scene, Lane is weeping as he takes all the blame for the shooting, even signing a confession to that effect. A defiant Pembleton takes it to his boss, snarling, “I did this for you, Gee! I got him to sign on the dotted line for you!” He pauses, struggling to contain his fury and disappointment, then quietly adds, “He would have stood a better chance in the back of a paddy wagon, with jackboots and clubs. He would’ve gotten a fair shake.”

He’s right, of course, because clearly no threat of violence, nor any beating, could ever have the coercive power of Frank Pembleton — and Andre Braugher — turning his mind and his voice upon a suspect. It is an utterly mesmerizing, stomach-churning performance by both character and actor, and the only reason it isn’t obviously the best moment of Braugher’s career is because there are so many others just as great. He wasn’t even meant to be the leading man of Homicide — Kotto and Ned Beatty were bigger names, Daniel Baldwin was a Baldwin brother at a moment when that idea meant something, etc. — yet the show quickly began to orbit around its unexpected but unmistakable new star.

It’s one thing, though, to go from straight drama to a tonal hybrid like Men. It’s quite another to go from the heaviest of heavyweight material to the silliest of silliness. Yet that is what Braugher did, with incredible grace, comic timing, and willingness to make himself the butt of the joke, when he signed onto the cop sitcom Brooklyn Nine-Nine.

Braugher won an Emmy late in his run on Homicide, and another for starring in a dark, riveting 2006 FX miniseries called Thief. In that period after Homicide, he headlined several other network dramas and did memorable guest appearances, like playing Hugh Laurie’s therapist when a House M.D. season opened with the good doctor suddenly being a patient in a mental hospital. No matter where Braugher was, or whom he was playing scenes against, you couldn’t take your eyes off him.

He could have continued in that vein for the rest of his career, mixing in the occasional movie supporting role with well-paying TV gigs that took advantage of his voice and his commanding presence. Then he took a role on Men of a Certain Age, a dramedy for TNT(*) about a trio of middle-aged pals — Braugher played Owen, an ineffectual, overweight car salesman working at the dealership run by his overbearing ex-athlete father — co-created by comedy veterans Ray Romano (who also starred) and Mike Royce. On Wednesday night, Royce recalled that when Braugher’s agent expressed interest in him playing Owen, “We scoured the internet for clips of him being funny. And we couldn’t find any. It was all dramatic. But he came in and read with Ray, and he was good, and Ray said, ‘Watch, everyone’s going to say he’s the funny one.’” And everyone who watched did. Braugher so expertly captured Owen’s beta male frustration that he wound up generating most of the show’s laughs, while his more comedy-experienced co-stars Romano and Scott Bakula handled the darker stuff. The ratings were low, but Braugher got two more Emmy nominations out of the job, deservedly.

(*) Unlike Homicide, this one is easy to find at the moment, with both seasons streaming on Max.

It’s one thing, though, to go from straight drama to a tonal hybrid like Men. It’s quite another to go from the heaviest of heavyweight material to the silliest of silliness. Yet that is what Braugher did, with incredible grace, comic timing, and willingness to make himself the butt of the joke, when he signed onto the cop sitcom Brooklyn Nine-Nine. His character, Captain Raymond Holt, had nothing in common with Pembleton other than their appearance and the fact that both were effective police officers. Holt is such a stickler for the rules, and so emotionally closed off, that Andy Samberg’s Jake Peralta initially compares him to a robot. Yet Braugher’s delivery was so dry that Holt’s lack of expressiveness became the series’ most reliable source of humor. And over time, the Nine-Nine writers realized that Braugher’s commitment to staying in character could allow them to have him do or say all manner of ridiculous things, and it would still ring true to the man Peralta and the audience first met.

Scene after scene, season after season, Braugher would sell jokes with the skill and aplomb of a Second City veteran. The man who had once played the most intense cop on television was now playing the funniest cop on television — frequently the funniest character on television, full stop. Eventually, Nine-Nine paid direct tribute to Pembleton, with an episode — titled, of course, “The Box” — that was an episode-length interrogation by Holt and Peralta of a murderer who could only be convicted if they talked him into confessing. You can guess what happened, but the remarkable thing was that at no point did it feel like Braugher was engaging in self-parody. Yes, Homicide had once devoted an episode (Season One’s “Three Men and Adena”) to a single interrogation like this, but Braugher was playing Ray Holt as Ray Holt, not winking at the camera, not in any way straying outside the character he’d been given to play.

Though the bulk of his work was in Los Angeles, Braugher, his wife Ami Brabson (an actress who played Pembleton’s wife), and their children lived in suburban New Jersey. As the TV critic for The Star-Ledger of Newark, I interviewed him in 2000 at a diner near his house. Over two impressively greasy plates of breakfast food, we talked about his career, and about his new job as star of the ABC medical drama Gideon’s Crossing.

I could have only asked him Frank Pembleton questions for hours — after a while, in fact, he politely but pointedly suggested that it seemed like I was doing just that. In the end, though, what stuck with me wasn’t his discussion of his amazing craft, nor his inadvertent hint of where his career would eventually go. (“I’ve been accused of being ‘a serious actor,’” he told me, years before he’d get to play Owen or Captain Holt, but, “I can be a very funny guy.”) No, the part that stayed with me wasn’t about Andre Braugher, world-class thespian, but rather when he talked about how he had worked out to a science how to maximize time with Brabson and the kids, despite working 3,000 miles away from them. (Years later, people who worked with him would tell me stories about how speedily he could make it to the airport whenever there was any kind of pause in production.) He added that it was important to him and Brabson that their children be raised in “a true context,” rather than as the offspring of a famous actor growing up in a company town.

“It’s very easy,” he told me, “and we’ve seen it happen before, other cases in which people forget where they came from and what made them, and the context in which they lived. And they begin to believe their own hype and think they’re the best thing since Swiss cheese. And for those things that I’ve done which are worthy of admiration or acclaim, I put them in the proper perspective. Being a husband and a father are, in my mind, greater accomplishments than what I play on television.”