My Policeman Is a Stunning Novel. How Does the Film Stack Up?

Spoilers for the My Policeman book and film below.

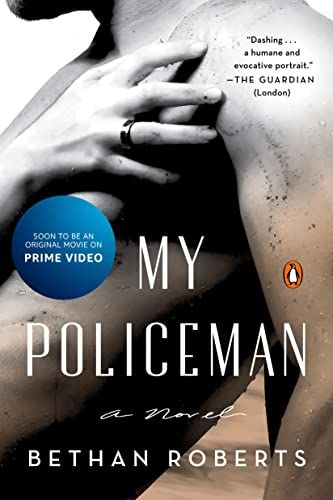

If you first came to know of the 1950s-set romantic drama My Policeman as “that movie starring Harry Styles as a gay cop,” well, consider this article a safe space. As a matter of fact, the 2012 novel by British author Bethan Roberts—the film’s source material—owes most of its American readers to the pop star. Though it was met with quiet acclaim when first released in Britain, My Policeman flew so far under the radar that it wasn’t even published in the U.S. until last year.

And the novel might have remained an obscure, “the girls that get it get it”-type gem until Amazon announced its Styles-starring adaptation in September 2020. (Styles was even photographed with the book earlier that year, and the novel made appearances on TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube.) The existence of the film—and Styles’ involvement in it—ignited a firestorm of interest in Roberts’ nearly decade-old book, and an American edition hit shelves for the first time on Aug. 3, 2021.

In case you’re unfamiliar, My Policeman follows a doomed love triangle in postwar Brighton: A young policeman named Tom Burgess (Styles) marries schoolteacher Marion (Emma Corrin), his sister’s childhood friend—but his heart belongs to Patrick Hazelwood (David Dawson), a slightly-older man who works as an art curator at the local museum. The book and the movie alike jump between the 1950s, following the events at the story’s heart as they unfold, and Marion and Tom’s life as a retired couple in the 1990s. In the latter timeline, Patrick has recently had a stroke, and—against Tom’s objections—Marion has taken him out of hospice to care for him herself at the Burgess home.

Even at a time when queer media has progressed past the need for tragic tales from straight allies about secret love affairs, Roberts’ novel is a stunner. Told in hauntingly elegiac prose, My Policeman—the book—is a sorrowful story about the ways in which expectations of conformity harm us all. As Christopher Bollen puts it in his New York Times review, “It is Marion who is cast as the outsider and interloper, and her cravings for Tom are rendered in a manner that has traditionally been reserved for unrequited homosexual yearnings. … Meanwhile, Patrick, who does have fulfilling sex with Tom, harbors a more conventional fantasy, ‘as though we were—well, married.’”

So how does the movie measure up to the book?

While the film is a clear tribute to the passion and dedication of all involved with its making, it unfortunately leaves quite a bit to be desired as, well, a film. It’s beautiful to look at, but it leaves the viewer cold even as it makes a transparent play at manipulating the audience’s emotions. Ultimately, the movie suffers from an overly literal adherence to the source material: In some respects, it is scrupulously faithful; at the same time, the script eliminates or heavily truncates some “minor” subplots that have an outsize impact on the feel of the entire novel. As for the million-dollar question of Styles’ performance, it turns out that the less he speaks, the better he fares. That’s not a dig at the man’s acting abilities—or, at least, not only a dig—so much as an observation that Styles brings to his role a magnetic sort of physicality that is best allowed to stand on its own.

As for the changes that the adaptation makes to Roberts’ original version of the story, many are minor: Tom gives Marion her swimming lessons at the local pool, rather than in the ocean; Patrick confides to Tom that his ex-lover Michael was beaten to death by a mob, whereas in the book we learn that Michael died by suicide. But some changes are more significant than others. Here’s what die-hard fans of the book should know before seeing the movie.

Marion and Tom’s Youth

Both the film and the book open in the 1990s before flashing back to the story’s pivotal events. In the book, Marion first takes us back to her school days, when she first became friends with Tom’s sister Sylvie and began to admire Tom from afar. As Marion grows into an adult, she makes the choice to become a teacher, sets her sights on Tom, and schemes to get his attention; at the same time, Tom prepares to serve in the military and contemplates what to do with his life before finally settling on becoming a policeman. Marion’s frequent visits to Tom and Sylvie’s home also offer readers some insight into Tom’s early life and upbringing.

In the film, though, the earliest flashback takes place after Tom has already returned from the War. At this point, their identities are already set: He’s working as a policeman, Marion is a teacher, and they already know each other—if only peripherally—from childhood.

Marion’s Friends

In the book, Marion is childhood friends with Tom’s little sister Sylvie, and Sylvie’s relationship with her eventual husband Roy provides a stark contrast to Marion and Tom’s marriage: Where Marion works and never has children, Sylvie becomes a stay-at-home mom; where Tom proposes to Marion despite not being attracted to her, Roy has an active sexual relationship with Sylvie but refuses to marry her until she lies to him about being pregnant out of wedlock. Sylvie is also the first character to express suspicion that Tom might be interested in men. By contrast, Sylvie appears for less than a minute in the entire film. In the scene where Tom agrees to give Marion swimming lessons, rather than implying that Tom might be gay, Sylvie tells Marion that Tom likes “busty women.” Even though Sylvie isn’t a huge character in the book, her role as Marion’s foil feels significant enough that it’s odd not to see her in the movie.

Sylvie isn’t the only one of Marion’s friends who gets short shrift. In the book, Marion befriends Julia, another teacher at the school where she works. Marion admires Julia’s independence, and her coworker’s kindness becomes a lifeline for her—until Marion ruptures their friendship by declaring that she views queerness as immoral and unnatural, which prompts Julia to come out to Marion as a lesbian and end their friendship. The regret that Marion harbors over the end of her and Julia’s relationship is nearly as significant as her conflicted feelings about her husband’s queerness.

Julia does make several appearances in the adaptation (and her coming-out scene makes it into the film intact), but her role is so substantially cut down that the audience never even learns her name—and the aftermath of her and Marion’s falling-out doesn’t figure into the story at all.

Patrick’s Health

In the film, as in the book, Patrick arrives at the Burgess’s home in the 1990s following a stroke that has severely impacted his physical capabilities. In the book, he is barely able to do anything at all except grunt and glare; the afternoon when Marion hears him calling out for Tom is a pivotal moment because it marks the clearest communication Patrick has engaged in since he arrived. In the film, Patrick is quite a bit more active—and healthy enough to campaign for Marion to let him smoke his beloved cigarettes. While his speech is still significantly impaired, he can and does verbalize a close enough approximation of what he wants to say that Marion is frequently able to understand him. What’s more, he is able to get around the house on his own when he is in his wheelchair.

The prognosis for Patrick’s ongoing condition in the film is also considerably different than in the book. In the novel, Patrick’s doctor repeatedly urges Marion to accept the fact that he’s not getting better, that there is no hope whatsoever for his recovery. In the adaptation, things are grim, but not hopeless: towards the end of the movie, Marion observes to Tom that Patrick is getting worse, but she insists that he still has a shot at getting better if Tom would only show up for him. In the final scene, as Tom clasps his hand on Patrick’s shoulder, the audience is led to believe that Tom just might pull through for Patrick after all—and that the star-crossed lovers will finally get their happy ending.

Watch My Policeman on Prime Video

Keely Weiss is a writer and filmmaker. She has lived in Los Angeles, New York, and Virginia and has a cat named after Perry Mason.