Where Do We Draw the Line Between Clothing and Costume?

Surrealism is staging a fashionable comeback.

One evening in April, I was deep in a rabbit hole of browsing the Ssense website when I happened onto something so bizarre that it made me question whether or not I was still in possession of a sound mind. The item in question was a pair of sickly-green knee-high boots; each boot had not a square or almond toe but four splayed digits, resembling an alien foot. They were less “footwear” than “partially sentient creature that appears to have wriggled out of Shrek’s swamp.” As I attempted to determine what type of customer might purchase these $1,650 boots, all my molten brain could scrounge together was “slime fetishist” or “costume designer outfitting a community theatre production of Flubber.” (I later found an image of Tessa Thompson wearing a version of them in black with a metallic-gold shredded mini-dress at a 2021 Met Gala after-party, but even her insouciance couldn’t convince me of the appeal.)

The boots are a twisted creation of Avavav, the Florence-based brand whose creative director, Beate Karlsson, is responsible for other preposterous garments such as a dress that appears to be sprouting goitres from the hips and a pair of silicone bike shorts crafted to mimic a photorealistic ass, nicknamed “The Bum.” The very existence of such garments raises the question “Where do we draw the line between clothing and costume?”

People wear costumes to transform themselves into someone else. They are pantomimes, used to escape one’s present circumstances. But the startling garments I’ve seen lately don’t seem to reflect a desire to place oneself within an alternate reality; rather, they seem to be a manifestation of who we are. As renowned fashion critic Sarah Mower wrote in her review of Loewe’s Fall 2022 show, “In times when reality becomes outrageous and nonsensical, it’s only logical that fashion should start to reflect illogicality.” In a world where there are no rules and nothing matters, the only thing left to dress up as is ourselves.

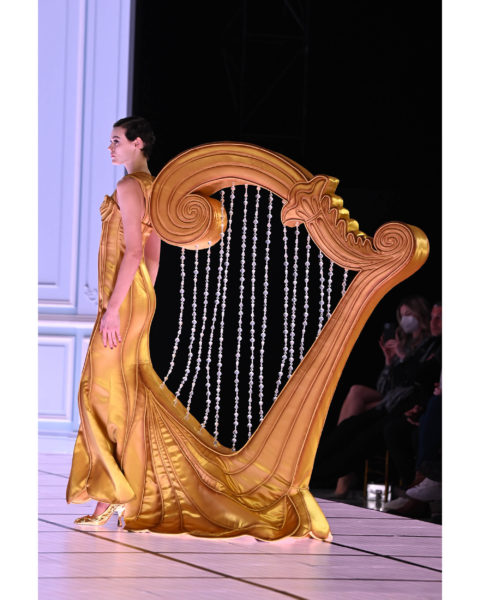

The Avavav boots join a litany of other bizarro items that while not exactly “taking over” are certainly ascending in popularity. The Fall 2022 runways were dominated by surrealistic elements, like Loewe’s balloon bustier dresses and Moschino’s musical-instrument ensembles. Even eternally ladylike Dior embraced eccentricity with glow-in-the-dark tubes sewn onto bodysuits. The ascendancy of new style icons like Sara Camposarcone, a content creator based in Hamilton, Ont., whose style resembles what the unholy love child of a clown and a fairy princess might wear, and New York’s Clara Perlmutter, better known as @tinyjewishgirl on TikTok, who looks like a Gen Z reincarnation of a ’90s club kid, confirms that after a long absence, irony and freakishness are back.

Every day is like Halloween more than two years into a global pandemic in which the simple act of getting dressed has become a celebration of life. Perhaps clothing has become so anarchic to compensate for the fact that living through one of the scariest imaginable events in human history has turned out to be less like the dystopian film Mad Max and more like Groundhog Day — just with more screen time.

“I gravitate toward colour and sparkle because they bring me joy,” says Shea Daspin, 32, an LA-based stylist who describes her approach to dressing as similar to the technique artist Marcel Duchamp popularized, in which he created sculptures out of a variety of found objects. Daspin began dressing like Rainbow Brite on acid at the age of 13 after discovering Japanese street-style magazine Fruits, which has been her stylistic North Star ever since. “I have a lot of different personalities within me, and it’s almost like I want to express them all at the same time,” she says. One day she might dress up as a rich Park Avenue socialite, another day as a handler at the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show. But don’t call it a costume. “Just because something is over-the-top doesn’t mean it’s a costume,” she says.

Growing up, Daspin’s unconventional style marked her status as an outsider. But as culture has become more receptive, even celebratory, of wild clothes, she now sees her wardrobe as a way of spreading happiness to strangers. “It’s not a form of activism per se, but it’s hard to see a bunch of sparkles and not think ‘That’s fun.’”

The hunger for endless whimsy may also be a side effect of experiencing the world primarily through screens. Boring outfits simply don’t capture your attention when you’re scrolling endlessly through an app. It’s always the more outlandish the better, which is perhaps why TikTok trends like “clowncore” and “night luxe” are seemingly ephemeral, appearing and disappearing so quickly.

The prevailing appetite for absurd clothes is not only an outcome of the past but also a vision of the future. Much is being made of the metaverse — a parallel virtual reality in which inhabitants can outfit themselves like the avatar in a video game, donning dresses covered in scorching flames, for example, or veiled in a cloud of mist. In the metaverse, anyone can dress like it’s the Met Gala, even if they’re at home in sweatpants.

Fashion — and culture at large — is in the midst of a mass reimagining of possibilities. Previous boundaries — such as not being able to wear a dress that’s on fire — no longer apply. Even if an item doesn’t initially make sense in real life, it might feel at home in a digital archive where a person can still experience the playfulness of dressing up without being subject to real-world limitations.

Perhaps the nonsensical Avavav slime boots didn’t compute for me, not because they are ridiculous or impractical but because they weren’t meant for the earthly realm at all.

This article first appeared in FASHION’s September issue. Find out more here.