My Life Was So Broken That I Pawned My Olympic Gold Medal

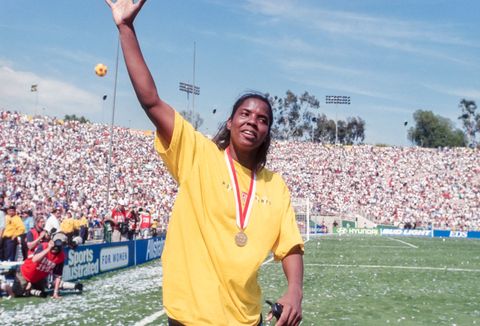

As a little girl, soccer star Briana Scurry dreamed of going to the Olympics. When she made the U.S. Women’s National Team alongside greats like Mia Hamm and Brandi Chastain, that dream came true. Scurry, the team’s goalie, helped USWNT win gold at the Atlanta Games, the first time women’s soccer was ever played in the Olympics. Scurry went on to win a second Olympic gold medal in 2004, cementing her status as one of the best players in the history of the sport. She was also the first female goalie inducted into the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame, and remains the only Black woman.

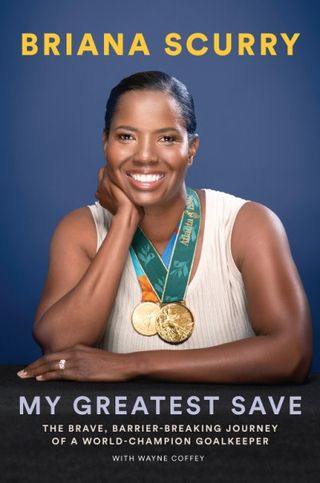

The accolades were great, but eventually the shiny veneer of Scurry’s success cracked. Her career ended in 2010, when she suffered a severe head trauma. In pain and unable to work, she spiraled into debilitating depression and a debt so steep that she was forced to pawn her most prized possession: her gold medals. More than 25 years after the Atlanta Games, Scurry is opening up about struggling with her identity outside of soccer, and learning to love herself again. Below is an excerpt from her new book “My Greatest Save.”

Content warning: Mention of suicidal ideation. If you or someone you love is having thoughts of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK or text NAMI to 741741 to connect with a trained crisis counselor.

I walked to the left, past a parking lot and an adjacent building, following the sidewalk until I arrived at a security booth that I’d never seen manned. Beside the booth was a staircase that takes you down to the river. I descended twenty-one steps and got to a circular plaza overlooking a waterfall. This was Little Falls, though it looked plenty big to me, running probably two hundred feet across. A carpet mill had been located at this spot for more than a century; a plaque commemorates its history. I walked to the railing, slowly; it was the only gear I had. I watched the relentless power of the churning white water. Most loud noises bothered me but the constant roar of the falls was almost soothing. The misty coolness coming up from the water tingled against my face. It was the closest I’ve ever been to a waterfall. I peered straight down into the turbulence and in that moment it occurred to me that I could get rid of my pain forever in a couple of seconds.

It could all be gone that fast.

All I had to do was jump over the railing.

The speed was appealing, for sure, but for a non-swimmer, the churning water was a daunting sight. I took a step back.

Maybe I needed to rethink this.

A half minute passed and I was just standing there. I had a vision of myself in a dumpster with a gun. I didn’t even own a gun. There are dumpsters aplenty in north Jersey. I had no idea where this vision came from. It wasn’t going away.

That’s stupid, I decided. If I am going to kill myself, I need to do it logically, swiftly. Here I was at river’s edge. I didn’t have to buy anything or go anywhere. What could be more convenient?

I studied the frosty flow of the river, dazed and conflicted. Should I jump? Or should I walk away?

Two voices begin a debate so heated it was as if I could hear them out loud. They were almost as clear as the voice I heard in the 1999 World Cup shootout—“This is the one.”

Voice One: You’ve never quit anything in your life. You’re going to get the surgery, and your pain will be over. Your life is so close to turning around. Hang in there a little longer. You have so much to live for.

Voice Two: Nothing ever changes. The surgery won’t happen for months, if then. Your pain is worse than ever. Your life is going nowhere. You have no money and no job prospects. Once you were a world-class athlete and now you can barely make it to your mailbox. You have nothing to live for.

Back and forth the voices went, at fever pitch, a tug-of-war on a rope that is about to snap. A tabloid headline trailed through my brain:

Former Olympic Champion Plunges to Her Death. No Foul Play Suspected.

I looked over the railing again. I thought of my mother, signing “Hallelujah” in the kitchen in Dayton, Minnesota, and imagined what it would do to her when she heard that her baby took her own life. I turned around and walked back up the twenty-one steps.

The months dragged on in the studio. The mail didn’t often bring good news, so I wouldn’t get it every day. If my phone rang and it was anyone other than Dr. Crutchfield, Ben, or Heather—or my dear friends, Naomi and Kerri—I usually would not pick up. My world kept shrinking. The one thing I felt I could control was what I put in my body. My brain was a train wreck, but I wanted to make sure I ate good food. I did a lot of juicing—the healthy kind. I’d go to the supermarket and get a variety of fruits and vegetables—kale, pears, apples, pineapple, Swiss chard, cucumber, and anything else that looked green and good. For sixty straight days in the winter and spring of 2013, I had one meal a day, and I drank it. I felt cleansed.

For most of my adult life I saw every day as a fresh possibility, another opportunity to get better. I spent years devouring self-improvement books. When I wanted to learn more about spirituality, I read Deepak Chopra. When I wanted to learn more about finances, I read Suze Orman. I became an ardent follower of Tony Robbins, finding his life strategies and positive energy uplifting. A lot of people regard self-improvement entrepreneurs as nothing more than charlatans who get rich off gullible and self-delusional people, like me. I’ve never seen it that way. Learning and growing are some of the best parts about being alive. I loved learning about goalkeeping from Jim Rudy. When I started working with Dr. Hacker, our team psychologist, I was excited that I could train my mind the same way I trained my body, coming to view pressure not as a burden but a necessary passage that ultimately is what creates diamonds. Even during the frustrating final years of my playing career, I was fired up about pursuing what was next. When it looked as if broadcasting might be an option, I made it a point to learn about it. As I became involved in public speaking, I studied the masters of the craft so I could get better at it. And as the extent of my brain injury became apparent to me, I read audiobooks to try to get a grasp of brain science and why a hard knock to the head could have such long-lasting repercussions.

I’ve always believed that if you seek/ask/pray to (pick your own verb) God or the Universe or a Higher Power (pick your own noun)—and you do it with a pure heart—your prayer ultimately will be answered. It won’t be in your time. It will be in Her time. But it will happen. It doesn’t mean that you won’t have setbacks or hard times and that your whole life will be like a day at an amusement park. It just means that if you put positive energy out there it will somehow, someway come back to you. It happened for me after my career crash-landed when I self-sabotaged the 2000 Olympics. Once I owned that and earnestly began to pray for a way forward within two years I was at the pinnacle of my game. Before I met Naomi, I had a series of relationships that weren’t especially fulfilling or healthy, as much because of what I was bringing to it as anything my partner was. When I consciously, prayerfully sought out something richer, taking a hard look at myself and what I needed to work on, everything changed.

Naomi and I had six wonderful years together, and to this day she is an angel in my life.

By the winter of 2013, though, my storehouse of positive energy was lower than my checking account balance. I couldn’t summon any because I didn’t remember how to. More than two and a half years of pain and insurance-company roadblocks had beaten the life out of me. Depression hit me like a runaway truck on the Jersey Turnpike. My lawyer’s office called and said I had to come in for another hearing because the company submitted another objection to my getting surgery from Dr. Crutchfield.

They are breaking me, I thought. They are going to get what they want. They are going to get me to give up. I went across the street to Little Falls Discount Liquors and purchased my vodka. I could only afford a pint. Later that night, as I sipped my drink, I decided it was time to reach out to Borro.

I had an Olympic gold medal they might be interested in.

Before I could meet with the people at Borro, I had a trip to make. My gold medals were at my mom’s house, in a cedar chest in her bedroom. One of my sisters helped me out with the plane fare. My mom had been suffering from Alzheimer’s for a couple of years, and her disease was getting into the late stages. I wasn’t sure if she would recognize me and know my name, but she did.

“Boob,” she exclaimed. It was what she called me my whole life—a shortened form of Boo, because I liked to watch Yogi Bear and Boo cartoons as a kid.

“Meresie!” I exclaimed back.

She asked me about the USWNT—her brain was still stuck in that era—and inquired about my teammates, especially Mia and Lil.

“When’s your next game? Who are you playing?” she asked.

I explained that I wasn’t on the team anymore and that I had retired. I said nothing about my brain injury.

A minute or two later, she looked at me and said, “When’s your next game? Who are you playing? Did I already ask you that?”

My mom asked me the same things a half-dozen times over a one-hour visit. Each time, she asked me if she’d asked that before. As sad as it was to see the disease overtaking her, her same sweetness still shined through. Her brain may not have been working, but her heart was as huge as ever. She noticed I wasn’t wearing socks.

“Are your feet cold? I can give you some socks. I have a blanket we can put over them.”

“No, no, thanks. My feet are fine.” Her feet must’ve been cold, because she kept asking me about mine.

Near the end of our visit, I asked her if she minded if I took the gold medals with me.

She remembered she had them. I told her I needed them for some appearances I was making.

“You take them if you need them,” my mom said. “You won them, after all.”

I gave her a long, goodbye hug and flew home that night. Thirty-six hours later it was Borro Day, March 13, 2013, a Wednesday. I had already postponed it once because I didn’t have enough money for gas. I woke up feeling dread. I wanted no part of doing this but knew I had no choice. I showered and dressed, drank my smoothie, and got in my Jeep. It was a dreary, rainy day. On the passenger seat, inside a small wooden box, was my 1996 gold medal. (I was taking it one medal at a time and this was the more valuable one.) I got on Interstate 80 heading east, toward the George Washington Bridge, for the twenty five mile trip to New York City. I passed exits for Paterson and Hackensack and other places I knew nothing about. Everything looked gray and grim. At almost every exit, I thought about pulling off and turning around and going back to my jail. But I kept going. I talked out loud, to myself.

“This is going to be a good thing. It will give me room to breathe,” I said. I felt as though I wasn’t even Briana Scurry, or in my own body. I didn’t know who I was. I paid a thirteen dollar toll that I couldn’t afford, crossed the bridge, and headed down the West Side Highway in Manhattan. I passed the famous aircraft carrier, the Intrepid.

I’d never felt less intrepid in my life.

I got off the highway at Forty Second Street and drove across town. Borro was in a building near Bryant Park in the heart of Midtown. I parked in a garage. The battle within continued to rage. I thought about pulling right back out of the garage and driving home.

“This is going to be a good thing,” I told myself again.

I entered the building and pressed the elevator button for the twenty first floor. I walked up to the door. It was my last chance to turn around.

I walked in.

The receptionist greeted me warmly.

“Hi, I’m Briana Scurry. I have a one o’clock appointment.”

“Hi, Ms. Scurry. Yes, somebody will be right with you. Please have a seat.”

The office was nicely appointed and comfortable. Two loan advisors came out—a young woman and a British guy. Both were cordial and well-mannered. We sat down in a conference room. They offered me a bottle of water. I took the gold medal out of my backpack and put it on the table. I told them the 1996 Games were the centennial of the modern Olympics and the first time that women’s soccer had been a medal sport. I was trying hard to hold it together. I could tell they were intrigued by it.

“We’ve never had an Olympic gold medal before,” the British fellow said, opening the box. He picked it up.

“Wow, it’s heavy,” he said.

I told them I wanted to use the loan money to start a business. I was too ashamed to tell them the truth. They explained the process to me—that they had to authenticate the medal and then appraise it, and that it would take forty-five minutes to an hour.

“That’s fine,” I said.

They returned ahead of schedule and told me that everything checked out and went over the details. In exchange for my collateral—the gold medal—they would give me a check for $5,000. I would pay them $199 monthly for as long as the loan was outstanding. When I wanted to get the medal back, I would have to repay the principal plus fees.

My head was spinning. I asked a couple of questions about the repayment procedure. I signed all the paperwork. They told me that $5,000 would be wired to me in a few days. My Olympic gold medal was still in the wooden box on the table in front of me. It was the medal I started dreaming about when I was eight years old, watching the U.S. Olympic hockey team beat the Soviets in Lake Placid over thirty years before. It didn’t belong to me anymore, at least for now. We shook hands and said goodbye. I walked out the door of Borro, the leader in confidential, non-bank loans. I had to look at the parking stub to remember where the garage was. Back in the car, the passenger seat was empty. There was no more holding it together. I held on to the steering wheel and sat in my car and cried.

I’d hoped—perhaps naïvely—that having financial breathing room would be a panacea. It was anything but. It was a relief to know I could cover the basics for a while, but the realization that my life was so broken that I pawned my proudest possession took a heavy emotional toll. I thought about that gold medal all the time. I did what I needed to do, but I still was sick over it. The stress made my headaches worse and my depression deeper. Depression is a strange disease. It has its own ebb and flow, but it’s not predictable, like the tides. Some days I would wake up and feel a glimmer of hope, and my old upbeat worldview. Other times the gloom hung so heavily over me I was sure it would never lift. I could never pinpoint what caused the depression to lighten, or what made it hit me like a tsunami. The worst wave of it I’d ever experience came late one morning, a few weeks after I’d gotten the money from Borro. I had gotten up late. I felt untethered from everything on earth, as if I were just a random mass of cells. I went outside and turned left. The sun shined, and the air was crisp and sweet with the smells of blooming and spring. The aching in the back of my head had abated for some reason.

It’s a good day to die, I thought.

I never expected to be back in such a dark, despairing place, but here I was, walking back down the twenty-one steps to the plaza, past the marker for the old carpet mill. I was at the railing now again. The river was swollen from a few recent days of rain, the water falling hard into foamy rushing rapids. I put my palms on the railing. Jumping was something I had always been good at. I leaned forward and put my weight on my hands and tensed my upper body, and then, just like the last time, the lovely, light brown face of Robbie Scurry came before my eyes, and I could hear her say, “Boob, aren’t your feet cold?” My feet are fine, thanks, Meresie, I thought.

I wished in that moment I could thank her for all her love for all those years. I started to cry, tears spilling over the railing. I turned around and headed towards the steps. I never contemplated suicide again.

Excerpt from the new book My Greatest Save by Briana Scurry with Wayne Coffey published by Abrams Press Text copyright © 2022 Briana Scurry.