‘I Figured We Were All In’: Ben Stiller on That Crazy ‘Severance’ Season 1 Ending

This post contains spoilers for the finale of Season One of Severance, which is streaming now on Apple TV+.

The notes I took on my first viewing of the Severance finale, “The We We Are,” look like the scribbles of a madman, full of all-caps profanity, screaming at the characters to do all the things they were taking their sweet time doing. But that’s the genius of both the finale and Severance in general. As created by TV newcomer Dan Erickson and primarily directed by Ben Stiller, the show’s high-concept premise — What if a surgical procedure allowed corporate employees to literally separate their work lives from their personal lives? — built and built in tension and tragedy over the first eight episodes, then exploded in the season finale. In “The We We Are,” three of the show’s four main “Innies” (the corporate personalities) are able to temporarily take over their bodies in the “Outie” world in hopes of finding someone who could help them escape their unfathomably cruel existence. For Innie Mark (Adam Scott), this means meeting his Outie’s sister and brother-in-law, and discovering to his shock that corporate therapist Ms. Casey (Dichen Lachman) is in fact the allegedly deceased wife of Outie Mark. For Innie Irving (John Turturro), it is a chance to find his would-be lover Burt (Christopher Walken) after Outie Burt “retired” his Innie self. And Innie Helly (Britt Lower) discovers to her horror that she is a member of the Eagan family that has run the company for generations — a public family sacrifice designed to make the controversial severance procedure seem palatable enough to be voted into law.

“The We We Are” is filled with near misses and painful twists. Innie Mark unwittingly reveals himself to his manipulative boss Harmony Cobel (Patricia Arquette), who appears to kidnap Mark’s niece, but is really just racing back to corporate headquarters to stop the Innies’ rebellion. Helly is on the verge of telling members of the press about the torture they suffer, and Mark is about to tell his sister the truth about Gemma, when Ms. Cobel’s henchman Mr. Milchick (Tramell Tillman) forces his way past Innie Dylan (Zach Cherry) and seemingly returns control of the other three bodies to their Outie selves. Cut to black. To be continued?

It is a spectacular finale, and season, and worth discussing at length with Stiller. Over Zoom last week, he talked about why he wanted to end the season at such a precarious moment (particularly when Apple had not officially renewed the show at that point), the casting of all these crucial roles, when we might see Season Two (which was announced earlier this week), and a lot more.

A masked Ben Stiller, left, directing Britt Lower as Helly.

AppleTV+

The finale is almost unbearably tense. How do you go about creating that feeling?

The way we shot the show, we couldn’t shoot it episode by episode. We had to do cross-boarding, where we would shoot pieces from different episodes that were all at the same location. But I love 24, and in my mind, it’s sort of like our 24 episode. You have to just hope that everything up to that point has led to everybody feeling all the stakes of what was going on, and then we were going to be doing this real-time thing. But every episode of this show didn’t really come together until we were finished shooting the whole thing. Part of me was worried it wouldn’t be tense enough. And also, I haven’t had this experience before of doing a show where people are wondering what’s going to happen next, and what does this mean? It was all in a bubble. We didn’t know.

Ending the season at such a dark moment for the Innies is a particularly cruel twist of the knife. How did you decide that was where to cut things off?

We had a lot of discussions early on. It’s been a five-year process on this. I gave Dan’s script to Adam five years ago. Originally, we were going to go further and answer more questions, but I felt really strongly that there’s something about the mystery of the show that you want to live in. It is that balance of answering enough questions, but not too many. We settled on this because, in a way, it was the most emotionally resonant idea. Like, what are the numbers about versus the dilemma Mark is in. This seemed to be the pinnacle of that. I can only imagine how people are going to react, because I’m sure [there will] be a lot of different feelings about it, you know?

And also to do that when you were not guaranteed a second season? That was a bold choice.

I figured we were all in. Either we were going to be the most interesting and captivating one-season show, or we were making a move to force Apple to give us a second season.

Did you want Dichen Lachman to do anything in her performance to seed that idea that Ms. Casey was really Gemma, for anyone watching carefully?

I thought about that a lot. We all talked about it. You don’t want to give it away, and yet there has to be some idea of what is the connection. I feel like one of the reasons why people weren’t expecting this is because the character seems so disconnected and robotic. How that would play out and what that means for the severance procedure is integral to the storyline going forward. There’s a scene that I added that I really wanted to have, where he gets sent to the break room and she’s leaving it, and they pass each other in the narrow hallway. That was as close as I wanted to get to seeing a connection between these people. It’s funny: even the smallest look, I was nervous that was going to give too much away.

Arquette, left, and Scott, center.

AppleTV+

Mark is the character where we spend the most time with both the Innie and the Outie. What kind of conversations did you and Adam have about how to differentiate the two?

Adam really thought about it a lot coming in. He did a lot of work on his own that we didn’t talk about. The agreement is that they are two different parts of the same person, so he didn’t want to play them as if they were different characters. So, Innie Mark is that prototypical office guy who doesn’t really question the work. Where he starts out is something that Adam can do so well. And on the outside, the idea that he’s carrying so much more baggage, it was important for Adam to know that he would not [have] to be anything other than that guy. We talked about not having to worry about making him likable. He’s got a drinking issue, he’s not in a good place. I worried about whether people would be able to get on board with him. But I also felt that it was important to show him in the real state that he was in as a guy who would have done this procedure. Adam’s so good and so specific that he looked at everything on the inside very differently than he did on the outside, including the notion that the guy on the inside is only a few years old. The Innies are almost like children because they don’t have life experience.

The Innie world is so unusual and so specific to this show. The Outie world isn’t exactly the one we live in, but it’s much closer. Were you ever worried that the audience’s interest in the office scenes would outweigh their interest in the Outie Mark material?

Constantly, in terms of how to make the outside world as distinct and interesting as the inside world. The thing that’s going for the outside world is you have regular people with relationships. Devon and Ricken are especially important in that aspect, to have actors that the audience could invest in, and I thought Jen Tullock and Michael Chernus were so good for that. Stylistically, I wanted it to feel somehow as stark in its own way and generic in its own way, too. To try to not see specific brands, to not set exactly what time we were in. Shooting in winter really helped us, because there’s darkness, and that feeling of isolation was really important to the mood of the outside world.

Tramell Tillman as Milchik.

AppleTV+

Tramell Tillman is probably the least well known actor in the cast, and he’s giving one of the performances people have most gravitated towards. What did you talk about with him in building that character?

There are a lot of unanswered questions about Milchick that can be filled in by the audience and the actor. We talked about it a lot, but there were choices that he was making that, sometimes, I wasn’t totally privy to. He hadn’t done a role like this that had so much scope, and it was fun to watch over the course of the shoot how he gained confidence in doing what he’s doing. He’s so precise as an actor. He can be so still and interesting to watch, doing nothing. Patricia’s like that, too, because both of them have so much going on inside.

I was talking with an actor friend who loves the show, and he said one thing that strikes him about that performance is that when Milchick is warm, “He’s not a guy who’s pretending to be warm; he exudes goodness.” How does he do that and make it feel part of the same character as the guy torturing people in the break room?

It’s a good question. Getting to know him from doing the show, he’s such a warm person and he evokes this great energy, and yet he can also just turn the switch. I don’t know what it is about him that has both aspects going on. I know he takes his work very seriously, and he’s got a great theater background. But him as a person, he has a natural thing that just comes out, and is very much something you want to hang around and be a part of. But he can turn that switch for sure.

You and Patricia go way back. Do you have a shorthand at this point where she just comes in knowing what to do? Or do you still have to break down the character together first?

It’s so funny, because we did Flirting With Disaster [in 1996], and then we didn’t work together until [Escape at] Dannemora [in 2018]. We ran into each other occasionally in between, but I really do feel like I’ve gotten to know her so much more over the last five years. I feel this real brother-sister thing with her, where she has this really weird sense of humor, we have the same reference points that make us laugh. So I feel a comfortability with her. She’s a brilliant actress, there’s no pretense: “Try this, try that.” We were finding this character along the way. I had an idea, she had some ideas, but it’s never contentious. And by the end of the process, we had figured it out. That’s what’s great about her. She’s willing to search and try and not settle on something.

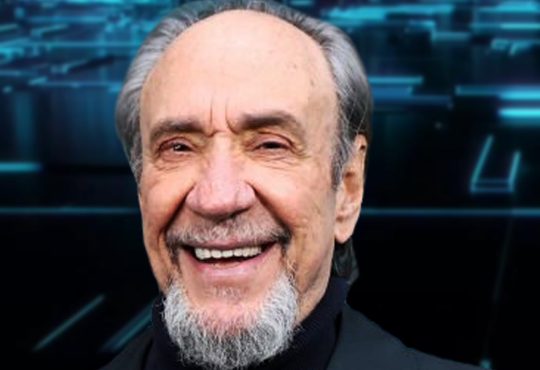

Christopher Walken and John Turturro.

AppleTV+

With the Irving and Burt love story, how did Turturro and Walken find the emotions in that relationship?

Turturro suggested Chris for the role when I was talking to John about [playing] Irving. They have a friendship over the years; they’ve worked together a few times. Those two guys are so good and so experienced. I know Chris, but not well; he worked with my dad [Jerry Stiller], and I worked with him years ago. I’m a huge fan of his. But I’d never directed him. He comes so prepared. He knows every line, he’s ready to go. He and John just really enjoyed playing with each other. As a director, I’m just staying back and maybe offering an idea to try something. But I’m really being an audience with them. And John came in with such a clear idea of Irving, too. At first, it was so specific that I had not envisioned Irving sounding like that. And he said, “No, I really feel like this is the guy.” Credit to him that he can take this affected accent and it became a real character. After a month or two of shooting, I could never [imagine] Irving sounding a different way.

It’s really remarkable how much feeling comes out of these tiny little interactions, like them brushing their fingers together.

They fill it so much, and I give Aoife McArdle [who directed the season’s middle chapters] credit for doing a lot of that work on those moments with them. I’ve always trusted that, with an actor, if they have an inner life going on, you’re going to see it and you’re going to read it, especially with those two. So the smallest thing means a lot, especially in a world like the one we’ve set up. Because they never do anything but work, little things become big things. When you slow the story down, the events that are smaller become much more important. So a hand touch becomes very very meaningful in this world where the rules are so strict.

How many different readings did Walken give you of the line about baby goats?

He did have a few. That was an Aoife episode. The great thing about Chris is he’s aware that he’s Chris Walken, and that everybody is just fascinated with his acting and his speech patterns and how he does it. But I don’t think it affects him in any way. It all comes from an organic place. I got to sit with him for an hour when we were talking about doing the show, and he shared with me a little bit about his acting process. As an actor, it’s amazing just listening to Chris talking about how he does it. When he does the goodbye video [as Outie Burt] and says “Good job, buddy,” it always makes me laugh.

Zach Cherry as Dylan.

AppleTV+

Zach Cherry is a guy almost entirely known for comedy. What made you think he was capable of getting to those emotional places Dylan goes in the last few episodes?

Zach is such a unique actor. The first thing I saw him on was Succession. I was so blown away by his natural comedic vibe. He’s so unforced. At the beginning of the season, I said, “How do you feel about where we’re going to go with the character?” He hadn’t had a lot of experience doing scenes like that, but I could tell he was game, and he took it very seriously, figuring out how to approach those scenes. He’s just a naturally low-key guy, so even when he’s being intense, there’s a naturalness; it’s always still him. I think he’s a really special actor.

Zach is a crucial part of one of the most memorable sequences in the whole season: the Music Dance Experience, which starts off as this fun thing and then becomes very menacing and dark. I imagine that was a hard sequence to put together, both physically and tonally.

I was really excited about it. Dan and I talked about it the whole time: “Do we do it, do we not do it?” We figured out a way to make it integral to the story. The idea for it existed entirely before we figured out how to put it into that episode. I was always lobbying Dan, “Let’s do the Music Dance Experience,” because I thought it would be a fun, weird thing that could only happen in this show. But he wanted a story reason, and then we had to figure out the right music, the combination of the elements, Tramell’s talent as a dancer — which I had no idea about! The moves he came up with were just so interesting and weird and entertaining and amazing. Adam’s white-guy dance, the stiffest thing, that makes me laugh. Everyone had this very specific way of dancing, and the actors brought that. One of the moments I really like in that is when Milchick is setting it up and wheeling out the cart and pulls out the instruments, there’s a shot of Mark looking over to see what’s going on, and you could just see for Mark, in this situation, it was almost like a kid, so fascinating for an Innie to see what a Music Dance Experience is.

How much did you and Dan and everyone talk about what the Innies know about the outside world? Do they have musical memories of any kind? Do they have taste?

There was a constant conversation: “How much is ingrained, and what do they know?” How does Irving know how to drive a car when he’s on the outside? We had to make these decisions, and part of the fun of the show is what bleeds through that they’re not aware of. John thought a lot about Irving in terms of his Outie. And when we do get to Season Two, people will see little clues about what John has been doing in Season One about parts of Outie Irving seeping into Innie Irving.

Helly is our POV character in the Innie space. What did you like about Britt Lower that made her the right person for that important part?

I was really taken with her reading, because she had this depth to her and this look that to me felt like, Helly is rebellious and the one who creates the change. She had this very strong quality about her. I found her to be funny, and when she read with Adam, they had this chemistry. I didn’t realize they had done a couple of episodes of a show [Ghosted] a few years ago. She had a natural strength about her, and she had this iconic look, too, that felt to me like the vibe of this world.

What interested you about Dan’s script in the first place?

Sometimes you read something and you just connect with it. It reminded me of shows that I loved. When I started to read the office banter, I was like, “This is so much that I know from watching The Office and Office Space and this genre of comedy that’s developed over the last 20 years.” And then he was taking that and adding this other layer to it and flipping it around. So I thought this was unique. It reminds me of things I remember, but it was its own thing. And that got me really excited. It was just a gut feeling, but he had created a tone I hadn’t seen before.

Tillman and Lower.

Atsushi Nishijima/AppleTV+

What were some of your influences in directing this?

As you probably know, I love Seventies movies. And when [cinematographer] Jessica Lee Gagné and I worked together on Dannemora, we looked at photography, like Lars Tunbjörk, Lynne Cohen, and others. I always love looking at the [Alan J.] Pakula movies, just for the framing. So we had an idea of the vibe, visually. And tonally, humor-wise, the rhythms that Dan wrote reminded me of those great comedies. I just watched all of The Office with my daughter. I knew it was great, but it’s so amazing how funny that show is, and how simple it is. There’s a simplicity to that show in terms of these characters in that one environment, so the audience knows that when a situation comes up, you can almost imagine how the characters are going to react to it.

You were acting in your early twenties. Have you ever had to work in an office job?

Not really. The closest I came to working an office job was being a talent intern on Thicke of the Night for Alan Thicke in 1983. But that was like Xeroxing stuff, and walking the guests out. Like, I would walk Charlton Heston to his car. I worked in a camera store, as a busboy and a waiter. But I think my real experience of office culture is more from movies and TV shows, really.

Among other things, the show is a real triumph of production design. What did you want that main office space to look like?

The first thing I thought about when I read it was it evoked such a specific nothingness and blandness. So I knew we had to come up with a bland environment that would also be interesting. Jeremy Hindle came on as production designer. We knew we had to find the exterior of the building. It could have been Fifties, Sixties, Eighties, whatever. But it was really important to find that stark structure, and when we found the Bell Labs building [in Holmdel, NJ], we went off of the details of the interior of that building. We just wanted to have it be a mix of different influences, and to not zero in on an exact year. I think there’s a logic to all of the technology of the show. They want the severed people to stay severed, so they don’t want them to have digital technology where they could contact the outside world. And then you can think about things like when they renovated the last time, and how they intentionally keep it low-tech even then. All kinds of thoughts went into it.

In the finale, when we discover that Helly is an Eagan, my jaw dropped. How much of casting Britt was made with this revelation in mind?

We knew that when we cast her, and we knew she could pull that off. She has that sophistication. But I constantly thought as we were doing this show, “How much is giving away too much?” It was really hard to know. I’m glad that was a surprise for you. I know that there are endless Reddit theories, and some people guessed that. I am amazed at watching how people react to the show, how they will really dig into every single detail. Which is great. When we were making the show, I bet somebody [would] freeze-frame on the license.

Any idea when you may be going into production on Season Two?

The hope is that we would get into production by the end of the year.

And if you do that, would the show be able to be back in 2023?

Possibly, possibly, yeah.