‘Tokyo Vice’: What If ‘Miami Vice’ Had a White-Savior Complex?

In one episode of the new HBO Max crime drama Tokyo Vice, American-born newspaper reporter Jake Adelstein (Ansel Elgort) is running his Japanese editor Eimi (Rinko Kikuchi) through the many deceased victims of the elaborate criminal conspiracy he has uncovered. After a moment, she interrupts his generic descriptions to point out, “Jake, they have names.”

Hearing this, Jake looks ashamed. He has insisted to anyone who will listen that he is not seeking an exotic adventure to dine out on when he inevitably returns to his homeland — that he wants to treat Japan as his own country now, and to understand all he can about the culture of his new home. Yet Eimi has just called him out, correctly, for treating these people — who had complicated lives of their own, and loved ones who will miss them — as bit players in his own thrilling story in a foreign land.

In the moment, at least, Jake understands the mistake he has made. The question is whether Tokyo Vice as a whole is guilty of the same kind of emotional tourism that Eimi accused Jake of playing around with. It’s a messy issue that doesn’t have a clear answer by the end of the five episodes provided to critics for review.

There is a long tradition of Hollywood productions that feature white Americans as the audience’s POV into the the whys and wherefores of other nations. Ken Watanabe, who here plays Jake’s police veteran mentor Hiroto Katagiri, first appeared before American audiences in just such a film: the 2003 Tom Cruise vehicle The Last Samurai. Sometimes, these international journeys manage to feel genuinely appreciative and immersive(*), while others never manage to transcend their hero’s perspective.

(*) Unscripted television has often done quite well with this, particularly in food-based shows like Phil Rosenthal’s Netflix show Somebody Feed Phil and the late Anthony Bourdain’s various travelogue series.

Tokyo Vice, adapted from the real Jake Adelstein’s memoir by playwright J.T. Rogers, makes a number of sincere gestures towards the city in which its fictionalized Jake has settled. The great majority of the show is in subtitled Japanese. (Jake becomes the first white American reporter for his new employer in part because of his intuitive grasp of the language.) Characters like Eimi and Hiroto are allowed to exist as more than stock teacher figures who are only there to help Jake improve. There are also long stretches involving Hiroto and/or two warring yakuza factions that barely involve Jake, if at all, and instead present low-level gangster Sato (Show Kasamatsu) as our protagonist for a while.

But some of these good-faith attempts feel less convincing than the creative team might hope. What life Eimi and Hiroto have, for instance, comes less from the writing than from the performances by former Oscar nominees Kikuchi and Watanabe. There’s also another prominent American character, Samantha (Rachel Keller from FX’s Fargo and Legion), who works at a hostess club for local businessmen, and who becomes the third point in something of a love triangle involving Jake and Sato. She is a composite character (there is a different gaijin hostess described in Adelstein’s book, but she was British and never actually met him), who seems to exist as much to provide Jake with another English-speaking confidante as she does to add some familiar mystery and suspense components to the story.

HBO Max

Or maybe the issue is the actor cast to play Jake. Ansel Elgort, you may recall from the press cycle around the release of West Side Story, has been accused by multiple women of various instances of sexual impropriety, from texting an eighth grader a dick pic to sexual assault. Elgort has denied the allegations, but his presence casts a pall over the whole thing. Tokyo Vice isn’t just another story about a white guy spending time in Japan, but it’s this white guy? And even separating the artist from the art, Elgort’s performance is often an awkward fit. He can come across as smug even in scenes when Jake is meant to be humble and inquisitive, which undercuts the show’s attempts to position him as an underdog in a country that can have deep hostility towards white visitors, and even more for a Jewish man like Jake.

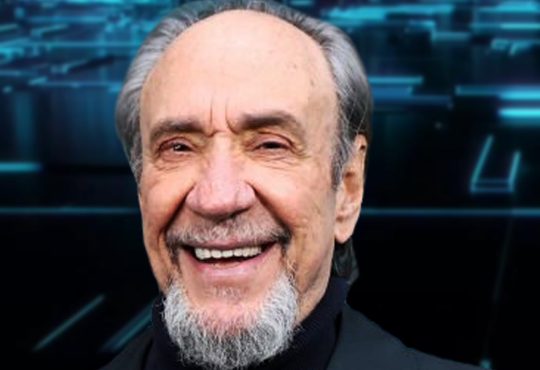

Unsurprisingly, Elgort is used best in the excellent series premiere, which is directed by Michael Mann. Though Mann never technically directed episodes of his iconic Eighties cop show Miami Vice, his visual aesthetic was as palpable in that show as it is in this completely unrelated Vice story. Early 21st-century Tokyo (most of the first season takes place in 1999) seems like it was built for Mann to shoot, with its abundant cool glass and metal surfaces, and its abundant neon signage. There are some gorgeous shots, particularly one of four different trains passing the same location at once while a man stands framed by all the tracks; the camera pulls out and we see that the man has been stabbed to death by an old-fashioned blade, contrasted with this modern backdrop. And whether we’re at the newsroom, the hostess club, the police station, or one of the hangouts for Sato’s crew, that first episode provides yet another example of how effectively Mann depicts people being good at their jobs. He also draws out a liveliness in Elgort that’s not quite there as he gives way in later episodes to directors Josef Kubota Wladyka and Hikari. The energy level of the series as a whole goes down, and it becomes more palpable that the plot is leaning on cliches from multiple pop cultural traditions.

The supporting actors are strong, even when their material isn’t. The more we get to know about Samantha’s mysterious backstory, for instance, the less interesting it is, yet Keller holds the screen effortlessly, whether she’s opposite Elgort, Kasamatsu, or any of Samantha’s coworkers. And while the show is for the most part fairly dour and self-serious, it occasionally generates some welcome light moments, as we see Jake working on friendships with his fellow reporters, with the cops (including Hideaki Itō as a cocky vice detective who seems less trustworthy than Hiroto), and even with Sato, who lures Jake into a debate about what exactly “that way” means in the chorus of Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way.”

In one scene, Jake and Eimi interview a Korean immigrant, and Eimi reveals that she has Korean grandparents. The mere mention of this biographical detail plays as fraught, given the complicated and often ugly history between the two cultures — which you can currently see dramatized in Apple TV+’s incredible Pachinko. That show also largely unfolds in foreign languages with English subtitles, but it doesn’t feel the need to give American audiences an American guide to the other side of the globe. Both series are adapting books with different approaches, but Tokyo Vice manages to make its version of its source material’s central figure into a drag on everyone else’s story.

Tokyo Vice definitely has its moments, including a prolonged yakuza action sequence in which swords ultimately prove more useful than guns. But it’s hard to not come away with the feeling that the show could have been so much more. At one point, Hiroto describes his father to Jake as “very Japanese.” When Jake asks what that means, Hiroto explains, “There are degrees.” This is a decent show, but one that feels like it would be much better if it were willing to be more Japanese.

The first three episodes of Tokyo Vice begin streaming April 7 on HBO Max, with two episodes per week being released weekly until the April 28 finale. I’ve seen the first five of eight episodes.