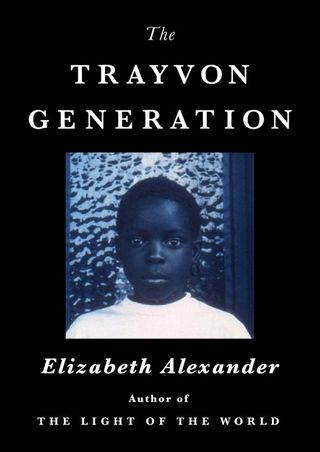

Elizabeth Alexander Examines the Trayvon Generation

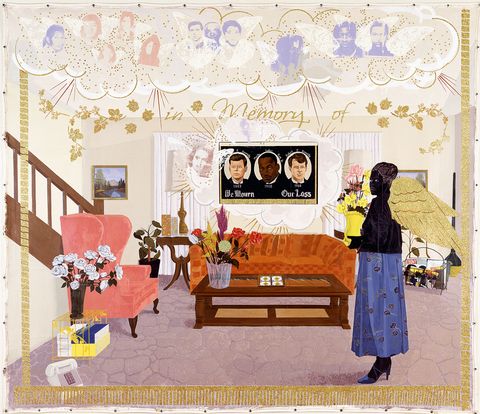

I want my children to be free. What does that mean? How much worry is enough and what is the affective power of a mother’s worry? I will continue this argument in a moment: the free Black men cannot exist without Black feminists. Free in this context doesn’t just mean having accomplished the seemingly impossible. It doesn’t just mean being outspoken. It means, to borrow from Langston Hughes, “free within ourselves” but in a way that is discernible and legible to those in our community.

I am a Black mother of two Black sons. I exult in them, their accomplishments and happiness and struggles. And I worry about them so deeply it enters what sleep I have, from time to time, and I dream, when I am not exhausted, dream my worries for them.

Every Black mother I know is exhausted in her own way. I think every Black mother must dream her fears about our children. I cannot write my dreams, for fear they will come true if I speak them into form.

One friend tells me of a dream she had where she was flying in an old-fashioned twin plane with her teenage son. They were flying in tandem, until she was suddenly ejected from the plane seat and fell, fell, fell to the ocean below. She looked up and saw her son continue to fly while the pieces of her side of the plane broke off: wings, engine, body. He continued to fly the half plane, but she knew it could not support him. Her desperation was animal and wild. “I pushed my body through the air to try to reach him,” she tells me. “And then the dream ended.”

Or Black mothers are not dreaming, because we are so exhausted that the dream space is without language or image, just darkness. If Black children belong to us—and we need not be mothers, or fathers, or even Black for Black children to belong to us—a part of us is always vigilant, and always exhausted.

In spring, I listen to communities of birds from my New York window, high above any treetops. They are migrating birds, a friend tells me, and some have come from as far as South America. She tells me that such birds have two-chambered brains that allow them to sleep as they fly. This is what it means to sleep with one eye open. I feel there is no better metaphor for the never-rest of people who love and take responsibility for Black children. And especially for Black mothers.

I tell my sons, who are young men, and the young people they bring with them into our lives, to care for each other and themselves. I tell them, also, that they cannot solve every problem, nor are they responsible for all woes. No one is. You cannot unknow inequity. Perhaps the greatest triumph is to live to tell and bear witness to the struggles of others. To understand that blood ties are not the only ties that bind. They cannot be. Without communal care and sense of responsibility, and bearing witness, we cannot know that we will survive into the future. I hope that we are as Langston Hughes told us we must be, free within ourselves. But our freedom must be seized and reasserted every day.

I wish for our young people freedom of movement, of thought, of imagination. That is why the brilliance of our writers and artists is so crucial for them, to learn from and to call them into their own imagining and self-expression. And our tradition has an infinite supply of stories of ingenious survival and making a way out of no way. We do not yet know what a more just future looks like. We do not fully know what freedom feels like. It will take many forms. I wish also for our young people rest from the unending labor that is race work, and from the spectral anxiety that is part of what it is to be Black.

Peter Kunhardt’s film King in the Wilderness chronicles the last year in the life of Martin Luther King, lonely as he leaves the ones he loves to do the work he must do and that he senses may bring him to his death. It is narrated by Dr. King’s friends and associates from that time, now elders, who tell us about that year. They are not only elders, they are survivors. And we understand the profound sacrifice and loneliness that can accompany visionary leadership and righteous work, as well as feeling a deeper sense of King the human being and the ideals he and his generation- mates were serving.

My father is one of those people who worked with Dr. King and other civil rights leaders, bringing them to the White House to meet with President Johnson and advance the shared goals and hopes of that period. He was a young man in his early thirties, working as special counsel to the president in that short, potent stretch of American history. In King in the Wilderness, my father is eighty-three. He leans forward into the camera when he speaks, eyebrows raised to open his face wide in urgency. “They discovered only after [King’s] death that he was more radical than they actually knew,” he says. “I don’t think he wanted us to take anything other than all that we deserve. And that’s what radicalism—in the best sense—is about: using the power that you have to transform the society for the better.” My father is a lion in winter among his fellow wise warriors in the film, still making his case for our humanity, as has been his life’s work and is now a bequest to our children.

Why do I end with my father in a film, when he is with us, and I have so many private memories of him imparting wisdom?

Because he was captured in a work of documentary art that lasts and carries on. It captures life force in its celluloid, or paper, or canvas, or digital files. It is not just for me or my children. It is for anyone within the sound of the movie’s voice. None of us shall live forever. But art and knowledge and wisdom can.

Art and history are the indelibles. They outlive flesh. They offer us a compass or a lantern with which to move through the wilderness and allow us to imagine something different and better.

John Coltrane’s eternal album A Love Supreme was made in one session in 1964, in the midst of the accruing violence of war and assassination. A refrain plays like the chanting Coltrane had come to understand in his religious practice, there is music, music, music, and no words. And after some minutes, we hear Coltrane’s voice recorded over and over, rendering it more powerful and himself not alone, and making community as he sings “A love supreme, a love supreme, a love supreme, a love supreme.”

What can the Black chant make happen? It sustains us. It is balm. It is remembrance. It is provocation. It is incantation. It is human. It is power.

The first time I heard this record I was nineteen years old in a college Black literature class, not new to jazz but new to such supreme transcendence. The students and professor sat together in a small seminar room and listened to the album all the way through without speaking. And the sound lifted us in ways we did not fully understand but knew had reached into our souls and asked us to be human together.

Almost all of the people in that room, Black and brilliant, have been dead for years. I remember them and carry what they gave me.

In his first book, Dear John, Dear Coltrane, Michael S. Harper made an inevitable-seeming juxtaposition of the refrain and Du Bois’s account of seeing Black body parts sold after a lynching: “sex fingers toes / in the marketplace.” I can hear Harper’s rich voice reading:

Why you so black? cause I am

why you so funky? cause I am

why you so black? cause I am

why you so sweet? cause I am

why you so black? cause I am

a love supreme, a love supreme:

The poem and the song answer for me the questions of what we sing and what we say when we are seemingly for- ever in the knot of a history that will not let us be.

Dear John, Dear Coltrane was made right after King’s trip to Memphis to support the striking sanitation workers, who carried signs that said, “i am a man.” Harper brought that plea for humanity into the poem, the voice of the artist Coltrane and the voice of everyday people asking to be treated as human.

The human connection has been all but gone in the last year of the global pandemic that has kept us apart from the people we love, the culture we need, and touch we crave, in a time when we most need to love and to grieve. Millions of people are missing the dead they were unable to comfort in their final hours and be with when they passed, or ritualize after they died. Half of planet Earth had been sequestered for nearly eighteen months. If we think we can measure the effect of that right now, we are wrong. The losses have been disproportionately Black and brown.

But if we are overstimulated by the technology that brings images to us, we are also connected by it. The art, the ideas, the words, the exchanges that teach and inspire us are more widely available to us than ever before. The ability to organize on the ground has now been enhanced by the ability to organize virtually.

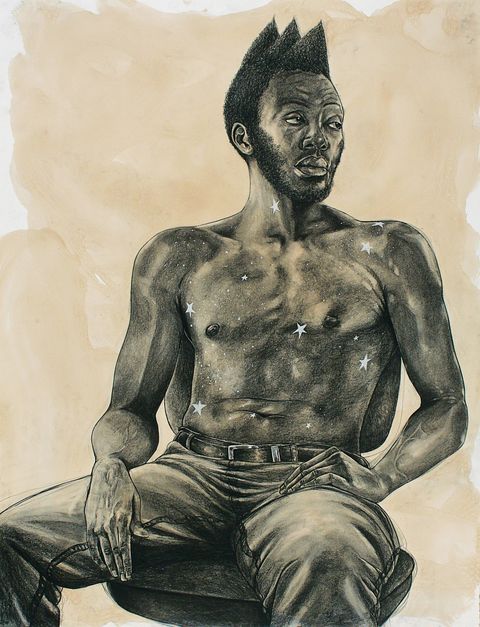

Artists make radical solutions all day long, soup from a stone, beauty from thin air. We see and try and discard and see again. We vision. We discard. We invent. We do it in the dark, we bring it into community. Artists continue to generate in a dangerous world that is nonetheless overflowing with life force and power. Creativity, making, and imagining animate Black self-determination with that which only culture can provide.

And people make movements and history with the force of creativity. The truly heroic drama of Black struggle is seen in the vivid figurative language of visionary leadership, the tableaux of fierce and proud resistance, the blazing beauty of people who survive indignities that might seem unbearable, the style and innovation with which Black people keep on stepping, offering countless examples to remind us of what has been overcome as well as to spark possibility for envisioning the new.

Sometimes the answers are not literal. Sometimes they take the form of human touch, of the love or encouragement that is transmitted in communities, or of the abstract space of possibility that is breath, carved out inside of us when we literally breathe to live and breathe to speak the truth. Artists are the visionaries who can help us imagine the unseen possibilities when we are faced with so much violence in what I fervently wish are the dying embers of an era of violent white supremacism, incivility, and hatred. We Black people were largely brought to this soil in the category of property. In the eyes of the law we were three-fifths human. Out of this status, we became the seers who have continuously articulated the problem, the hope, and the possibility of America. We have expressed the core of what it is to be human and to aspire to better enact that humanity. I believe we have been able to do this because we have accessed near-ancestral knowledge and wisdom—for our enslaved progenitors are within reach of memory and lore, still, in our families—as well as the energy, courage, and new sight of the young people who so often catalyze our movements. There is no progress without generations working together. And there is no North Star without vigorous creativity to imagine it for us and mark where it lights the way.

Excerpted from the book The Trayvon Generation by Elizabeth Alexander. Copyright © 2022 by Elizabeth Alexander. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.