‘Atlanta’ Kicks Off Season 3 With a Dark and Twisted Doubleheader

After a four-year wait that felt even longer, Atlanta is finally back. A spoiler-filled review of the third season’s first two episodes, “Three Slaps” and “Sinterklaas is Coming to Town,” coming up just as soon as you get me 300 pieces of fried chicken, all legs…

A perverse part of me wishes FX had not opted to debut two episodes tonight — that after this epic hiatus, Atlanta fans would have been greeted with a Season Three premiere completely devoid of Paper Boi, Darius, and anything we have come to expect from this show, even after so much time away. Starting solely with “Three Slaps” wouldn’t exactly have felt like a troll of the Earn-starved audience. After all, Atlanta has periodically done episodes where the main actors didn’t appear (the Nineties flashback episode “Fubu”), or ones in which they were largely bystanders (Alfred on the talk show in “B.A.N.”; Darius trapped in Teddy Perkins’ haunted house). “Three Slaps,” though, only brings in Earn at the very end, and is otherwise a pair of horror anthology vignettes — one short, one long — about the racism that’s so pervasive in American life, it even exists underwater. Yes, Atlanta viewers claim to love how unpredictable the show is, but presenting “Three Slaps” as their lone gift after such a wait would have been a fascinating test of that theory.

Instead, FX opted to go with a double feature that serves as a perfect thematic and stylistic pairing. Together, “Three Slaps” and “Sinterklaas is Coming to Town” are a reminder of everything Atlanta can be and do, whether it’s the stark nightmare of the former or the back-to-basics ensemble shenanigans of the latter. For that matter, they are demonstrations of how far the series can literally go, with the more traditional episode (if such a thing can ever be said of Atlanta) taking place 4,000-plus miles from the titular city. The episodes are connected by more than Earn waking up at the end of the first and the start of the second. For all its lighthearted goofiness, “Sinterklaas” still has room to depict the killing of a Black man in a way that’s even more upsetting than the monsters attacking the fisherman at the start of “Three Slaps.” And this second episode’s punchline is ultimately about how hard racism is to escape, even in a relatively enlightened place like Amsterdam.

As Al tells Earn during that second installment, “Same ratchet-ass hoes, different city.” Wherever Atlanta goes, there it is.

The season opens with those two fishermen, who are given interesting character names. The Black fisherman is listed in the end credits simply as Black, while FX’s press notes give the white fisherman’s name as Earnest. This Earnest opines on how whiteness is social rather than scientific, and that anyone in America can become white under the right circumstances — or be cast out of whiteness under the wrong ones. Then the Earnest we know concludes the episode waking up from what seems to have been the nightmare we just watched. In a surreal world in which ghosts can rise up from the murky depths, or Teddy Perkins can do everything in his power to make himself seem white, could the two Earnests who bookend “Three Slaps” somehow be the same man? Probably not. But whether Earn is literally waking up from two nightmares, one of which cast him as a white fisherman talking his buddy into his doom, the glimpses are very much linked, even as they are night and day from one another: two workaday guys in a modest boat in the dark, and a hip-hop manager in a blindingly bright hotel room next to the woman he recently had sex with. Two different kinds of fantasies involving two very different interracial pairings, and something of a mission statement for where Atlanta was versus where it intends to be now. But it’s also a reminder that trauma and history follows us everywhere, whether at the bottom of a lake containing the ruins of a self-governed Black community, or in a fancy bedroom where “Tupac Shakur” gets killed again.

The bulk of “Three Slaps” (written by Stephen Glover and directed by Hiro Murai) concerns Loquareeous, a hyperactive but fairly sweet kid whose enthusiastic outburst regarding an upcoming class trip to see Black Panther 2 instead gets him another trip to the principal’s office. His mother is arguably madder at Principal Miller and guidance counselor Mrs. Grier for dragging her in from work than she is at Loquareeous, but she still orders him to dance in the school hallway in an attempt to shame him out of the kind of behavior that could land him in real trouble once he gets a little older. And Loquareeous’ grandfather issues the episode’s titular three slaps across the face — relatively gentle ones, as such things go, but enough to get Grier to send social workers to their home, convinced Loquareeous is in a dangerous environment from which he needs rescuing.

The brief glimpses we see of his home life seem reasonably fine, though — especially compared to where he is soon to wind up. Loquareeous is not afraid of his mom or grandfather, he gets to eat spaghetti out of the fridge, and can sneak in some American Dad-watching when no one’s paying too much attention. But his mom also takes such deep offense to the social workers’ arrival — assuming, wrongly, that they’re there at her son’s request — that she defiantly releases Loquareeous into their custody. They in turn hand him over to Amber (Laura Dreyfuss from The Politician) and Gayle (Jamie Newmann from The Deuce), a lesbian couple presenting themselves as woke white saviors who are in fact abusing and exploiting their Black foster children. Gayle has a temper that scares the kids, while Amber talks to them in chillingly patronizing tones, attempting to rename Loquareeous as “Larry” and encouraging him to sing old-timey work songs while doing forced manual labor in their backyard(*). Loquareeous’ attempt to escape into the arms of a white police officer fails, because of course the cop would listen to these two sweet white ladies over him. A Black social worker temporarily assigned to the case sees through Amber and Gayle’s act — in part due to their household’s lack of washcloths (a noted divide between white and Black hygiene culture) — but she gets murdered by Gayle, and soon the two terrible moms are attempting a murder-suicide with Loquareeous and his new foster siblings, driving off a bridge reminiscent of the one from the fishing scene.

(*) Loquareeous first tries singing Gucci Mane, in a gag reminiscent of the Blazing Saddles scene where Bart and the other Black railroad workers harmonize on Cole Porter while their white overseers demand “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” or “Camptown Races.”

This all seems inspired by a true and tragic story of an abusive lesbian couple who used their role as foster parents to gain social media currency with viral videos and posts. In the real story, the couple managed to kill three of the kids and themselves, where “Three Slaps” blessedly declines to go that far. Loquareeous pulls off a daring escape and wanders back home, where his mother shrugs off his alleged rebellion. And a TV news report later reveals that the foster siblings also survived Amber and Gayle’s self-righteous belief that these kids would be better off dead than to go on living in a country with such contempt for Black people.

Even with that relatively happy ending, “Three Slaps” is a harrowing watch, whether in the genuine nightmare moments (the ghosts dragging Black out of the boat, the social worker’s head encased in one of Amber’s artisan pickle jars) or the more prosaic kind (Amber’s disgusting attempt at fried chicken, or her promising Loquareeous, “I’m going to love that pride right out of you”). Our brief glimpse of Earn at the end comes as a relief, as does most of “Sinterklaas is Coming to Town” (written by Janine Nabers, and again directed by Hiro Murai). The terrain is different, but the tone is mostly lighter, and our four friends are all back doing the things we love about them: Al scowling at the foolishness around him, Darius making non sequiturs (say, abruptly transitioning from talk of his balls being crushed as a kid in Nigeria to praise of the movie Food Fight), Van being intensely curious about the world around her, and Earn scrambling to solve everybody’s problems for them.

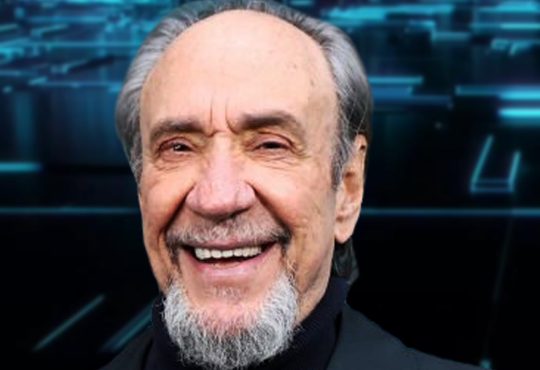

From left, LaKeith Stanfield as Darius and Zazie Beetz as Van.

Coco Olakunle/FX

Despite the new locale, “Sinterklaas” is an episode reminiscent of a variety of previous Atlanta tales. There are, for instance, European cultural traditions presented as something wholly alien to Earn and the others, like in the German festival of “Helen,” while the grisly euthanizing of the man who may or may not be Tupac can’t help evoking various Atlanta brushes with celebrity, most notably the final confrontation between Teddy Perkins and Benny Hope. But this familiarity is useful on multiple levels. It’s a reassurance after the departure of “Three Slaps” that the series hasn’t wholly transformed over its extended absence. And as “Sinterklaas” builds to the great punchline of Al walking out on his concert because the audience is filled with people in blackface as part of a local Christmas tradition, it’s a handy reminder that some problems will follow these characters to the ends of the earth.

The Tupac scene aside, “Sinterklaas” is mainly a reminder that, for all the praise we heap onto Atlanta for its tone, its versatility, its profundity, etc, when it wants to be, this is a spectacularly funny television show. And the humor often allows the larger points about being Black in America — or, now, being Black in the world — work. It’s a spoonful of Darius making the medicine go down.

Though Season Two ended with Al, Earn, and Darius heading off for a European tour, “Sinterklaas” quickly establishes that we are now seeing their second European tour — this one with Paper Boi as the headliner rather than an opening act. Between this and the “Three Slaps” references to a Black Panther sequel, it’s a way to pull the characters out of 2018 and into something resembling our present (minus the pandemic, of course), and yet another opportunity for Al’s rap career to significantly advance while we’re not paying attention. The question has never been, “Will Al make it big?” It’s always been about the consequences of his inevitable stardom, for both himself (having to play hilariously exasperated witness to two groupies trashing his hotel room when all he wanted was a simple threesome) and for Earn, who has clearly learned a lot about how the business works since we last saw him. For all the fires he has to put out throughout “Sinterklaas” — some of his own making, for forgetting to charge his phone on the last night in Copenhagen — he seems on top of it all. He knows how to exploit the contract rider to extract as much cash as he needs from local promoter Dirk. When the laptop gets left behind, he quickly figures out a way to get it to the venue. And when Al understandably refuses to perform for this particular audience, he knows enough to point out that Dirk’s insurance should cover him for the loss Al has just created. (And in a second wry punchline to the whole Black Pete business, Earn is able to escape Dirk’s wrath by disappearing more easily in this crowd than he would ordinarily be able to in a European city.)

The most Atlanta sequence of either episode, though, comes with Van and Darius stumbling their way into the strange and ultimately brutal farewell party for the man Darius assumes is Tupac. None of the other guests seem troubled by these interlopers (though several of them believe Darius is their photographer, despite him only having a phone to take pictures with), and the death doula offers Van a sympathetic ear and the unexpected — but not wholly unwelcome — notion of her and Darius as a couple. (This is yet another separate adventure they’ve gone on, along with the Drake house party episode from Season Two.) But the real Atlanta moment comes when it is finally time to say farewell to Tupac (or his doppelgänger), which involves not an injection or some other relatively peaceful euthanasia method, but the tarp over the bed dropping down to smother this man to death as he claws desperately at it, fighting to live with every last fiber of his being. It is less mercy killing than state-sponsored execution. Van is rightly dismayed by this spectacle, but everyone else reacts with Zen-like calm and solemnity, as if this is naturally the right way to send a Black man out of this world and into the next one. Even more than the blackface running gag, it is a proclamation about how little Atlanta has changed despite traveling so far from Atlanta itself.

Welcome back, Atlanta. How we have missed lunacy like this.