Rep. Ayanna Pressley Is Challenging Beauty Norms to Make Women of Color Feel Seen

When Ayanna Pressley won her election in November 2018, becoming Massachusetts’s first-ever Black congresswoman, she punctuated her victory speech with a question she’d worked hard throughout her campaign to answer: “Can a congresswoman wear her hair in braids, rock a black leather jacket, and a bold red lip?”

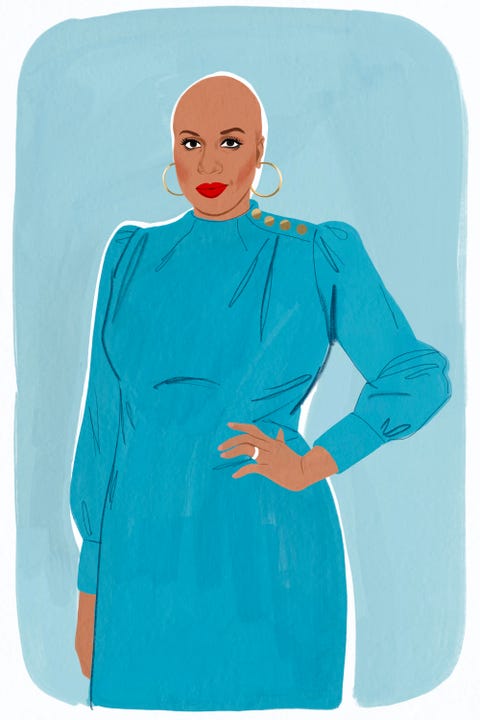

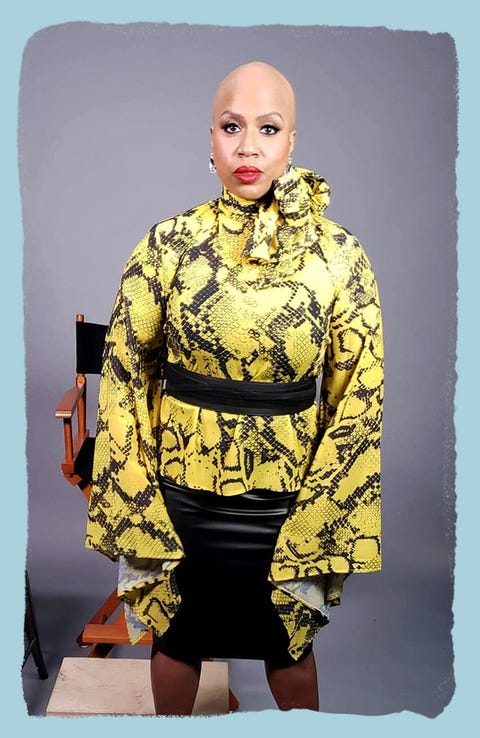

Fashion and beauty have long been hallmarks of Pressley’s approach to politics, using style as a way to share her authentic self with her constituents and the nation at large. And she hasn’t done it alone: In 2018, she linked up with image consultant and stylist Donyelle Shorter, and the two have collaborated on Pressley’s wardrobe ever since. But shortly after Pressley took office in D.C., both she and Shorter were thrown for a loop. Pressley began to lose her hair and was ultimately diagnosed with the autoimmune disorder alopecia areata. Without her signature braids, both women leaned on clothing as Pressley’s primary form of self-expression and as a way to reclaim her sudden transformation. “To let the world know: We’re here, and we’re bald, and we’re beautiful,” Shorter says.

ELLE’s series Clothes of Our Lives decodes the sartorial choices made by powerful women, exploring how fashion can be used as a tool for communication. We chatted with Pressley about how her style has evolved over the years and how you adapt when something you’ve come to treasure disappears.

When I first started working in politics, my inclination was to assimilate. I was often one of very few women and one of, if not the only, people of color in the room, and I tried to adopt whatever political or cultural currency would make it easiest for me to navigate these spaces. I really aged myself; I wore a lot of ascots. I wanted to be taken seriously and demonstrate that I knew the unwritten rules of the uniform. I was the queen of blazers, and I had pearls in every variation and iteration. But throughout my time serving as the first woman of color—the first Black woman—on the Boston City Council, I started to feel more emboldened. In 2011, I was decisively re-elected. I topped the ticket. I felt increasingly confident about my contributions and that my constituents were feeling seen and centered.

So I began to flex. I made the decision to grow my relaxer out and wear my hair in a natural state. I started to express myself through my clothes, and for that, I looked to my mother. I thought my mother was the most glamorous, fashionable person, and I loved that she was disruptive. She would often wear earrings that didn’t match, and when I asked, “Mommy, why are you doing that?” she’d say, “Because I can.” She would go to church in butterscotch leather jeans, a stiletto heel, a velvet blazer, and a Victorian blouse with a Farrah Fawcett flip. She’d wear red Fashion Fair lipstick. So then I started wearing a red lip. Whenever I was doing something where I knew I’d be met with resistance, I wore leather. I wore hoops. I wore a red stiletto. I felt this powerful tribute to my mother, and I felt more aligned with my authentic self.

Fast-forward to my run for Congress, I decided to get Senegalese twists for a vacation. When I saw myself in the mirror with these braids, I felt like I had met myself for the first time. I felt so connected. But when I returned from my trip, I received unsolicited counsel, by many well-meaning people, that I could not run for Congress and keep my twists. I told everyone, “These took hours. The vacation’s over, but I’m not taking them out. You’ll have to live with them.” Then I created this ethnic chignon with my braids, and young women started mimicking the style and sending me photos. I’ll never forget this young woman who posted on social media: “I received a call back for an interview for my dream job, but I just got box braids yesterday.” She then said, “I was going to take it out, but then I thought of Councilor Pressley.”

I went bald the night before the first impeachment [of former President Donald Trump]. At six in the morning, the day of the impeachment, I was getting a custom wig made because we were fearful that if I just showed up on the House floor on impeachment day with a bald head, the assumption would be that I was seeking to make a statement. Really, all I wanted to do was hide and heal.

I filmed my alopecia reveal video with The Root, and it was a very emotional day. There were a lot of tears. Without your hair, there’s such a vulnerability. You’re completely exposed in every way. I remember the first time I was taking photos without hair, and I instinctively went to pull my hair around my shoulder or to push a bang back. Losing my hair was such a traumatic thing because it was a transformation not of my choosing. And it was something I was going to have to do on a world stage.

What Donyelle did for me on that day—how she styled me—was so special. It set me on a pathway to healing. I felt peace. She restored something for me that I hadn’t felt up until that moment; she restored myself. But even after all that emotional labor and logistical labor to get that video done, I said to my team, “What if we release it and no one cares?” Imagine my complete surprise that it resonated with so many people around the globe. I was not prepared at all.

I had come to appreciate the power of representation as a Black woman with Senegalese twists, but I had not fully understood that I was also offering representation for those who have suffered traumatic hair loss. A dear friend of mine told me, “Your territory has been enlarged,” and at first, I didn’t understand what that meant. But there are seven million people living with alopecia. There are people who suffer traumatic hair loss because of other autoimmune diseases or because of cancer treatment or because it’s hereditary. One woman came up to me and said, “I suffer from female pattern baldness. Thank you for how you show up in the world every day. It means a lot to a lot of people.” The disability community embraced me immediately. Various advocates have shared their stories with me since the day that video hit. How many of them were DMing each other and tweeting at each other and texting, “Have you seen it? Have you seen it? Have you seen it?” I can look back now and say that it was a tremendous blessing.

Before losing my hair, I had never felt so secure about my aesthetic expression of my Blackness, of my womanhood. To be fully transparent, I haven’t gotten back to that place yet. I’m still very much on that journey. But I’m aware that how I show up in the world is disruptive. How I present myself is intentional, and it’s political. It’s political because I’m a woman. It’s political because I’m a Black woman. It’s political because I’m a Black bald woman. I’m not seeking to make people uncomfortable, but I’m also okay with that in the aim of progress. How I present challenges conventional norms and standards for what is beautiful, for what is professional, for what is appropriate.

What I seek to do at these specific inflection points in my advocacy or my life is to be unapologetic. To me, that means to be fully and authentically you, without pivoting or equivocating in order to make other people comfortable. Yes, I have hips and thighs along with these cheekbones and brown almond-shaped eyes. I have my father’s nose and this melanated alopecia crown. I’ve earned the right to show up authentically as myself, and I’ve been rewarded for it. If I were having struggles in advancing a policy agenda, in earning the trust of the electorate, perhaps I’d second-guess myself. But I’d like to think I wouldn’t. I’m 47 years old. I know who I am, and I stand in that firmly.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io