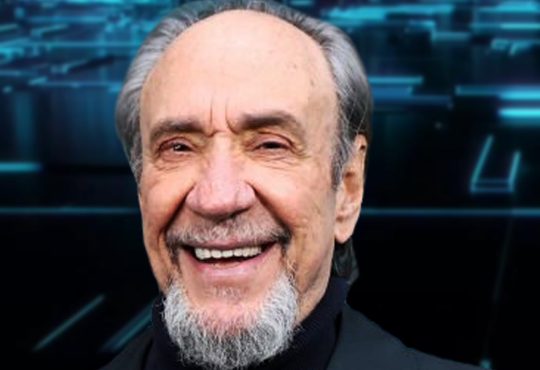

Ed Asner: A Working-Class Hollywood Hero

For nearly 40 years, Ed Asner was the answer to a great TV trivia question: Who is the only actor to win both drama and comedy acting Emmys for playing the same character? The legendary actor, who died Sunday at the age of 91, won three Emmys in the Seventies for playing curmudgeonly newsman Lou Grant on the classic workplace comedy The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and another two for translating the role into its acclaimed one-hour drama spinoff Lou Grant. Even when Orange Is the New Black‘s Uzo Aduba recently accomplished the feat, it was due to a quirk in eligibility for the same show — meaning that for the length of his impressive career, Asner was essentially a category of one.

Asner’s ability to translate Lou Grant from a multicamera sitcom to a gritty, issue-oriented drama — to make the character recognizably the same man in both formats, despite such wildly different tones — stood out because of the era in which he did it. Today, genre lines are so blurred that a show like Orange could plausibly be considered either a drama or a comedy; performers like Barry‘s Bill Hader win comedy acting awards for largely serious work on half-hour shows. But turning Lou from sitcom sidekick into dramatic lead simply wasn’t done back then. And that unprecedented transition beautifully sums up Asner’s entire body of work.

Asner’s look barely changed over a career that spanned eight decades — he was one of those actors who seemed to have been born old, and, on the surface, looked like a guy you didn’t want to run into in a dark alley at midnight (or a bowling alley, anyway). Yet he was able to play a wide range of characters, from monstrous villains to Santa Claus (a role he assumed more than a half-dozen times over the years), from a slave ship captain in Roots to the charmingly cranky widower Up. And while Asner could toss off some of the most iconic laugh lines in TV history in his landmark role (“You’ve got spunk,” Lou tells Mary Richards at the end of their first meeting, growling after a beat, “I hate spunk!”), he was also a serious political activist and labor leader behind the scenes, particularly as a two-term president of the Screen Actors Guild.

Raised by immigrant Jewish parents in Kansas City, Missouri (his mother was a housewife, his father ran a junkyard), Asner had already packed in a lot of living by the time he became a working TV actor in the late Fifties, at the tail end of the medium’s first golden age. He’d worked on a General Motors assembly line for a while, served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps for a few years, and was a founding member of Chicago’s Playwrights Theatre Company, which would eventually become the improv comedy institution The Second City. Those early jobs gave him a better appreciation for the travails of the working man, a legacy that deeply informed his SAG leadership in the Eighties. (He would later blame the cancellation of Lou Grant, a hit show and awards player, on his political and union work earning the disapproval of CBS boss William H. Paley.)

Asner worked steadily but mostly anonymously throughout the Sixties: two Gunsmoke episodes here, three Fugitive episodes there, even small roles in a couple of Elvis movies (the latter of which, Change of Habit, co-starred Mary Tyler Moore, though they didn’t work together in it), usually playing cops or other tough-guy parts. Every now and then a more prominent job would present itself, like playing the heavy opposite John Wayne in 1966’s El Dorado, but for the most part, Asner was a vaguely familiar character actor, for whom stardom seemed impossible.

His unlikely big break on Mary Tyler Moore came in 1969, as he was turning 40 and shopping a resume light on comedy. As he told The Hollywood Reporter’s Scott Feinberg in an interview conducted earlier this month, his audition did not begin well. “I plodded through the reading,” he said, “and Jim Brooks said, ‘That was a very intelligent reading.’ And I mumbled, ‘Yeah, but it wasn’t funny.’ They said, ‘Why don’t we have you back to read with Mary? We want you to read it all-out, like a crazy, wild, meshuga, nutso.’ So I said, ‘Well, why don’t you let me read it that way now, and if I don’t do well, don’t have me back?’ That’s a revolutionary statement. He said, ‘All right, we’ll try it.’ So I read it that way, like a meshuga, and they laughed. Jim said, ‘Read it just like that when you come back with Mary.’”

From that meshuga reading, TV history was made. The Mary Tyler Moore Show boasted one of the best and deepest ensembles any sitcom has ever had, both at the WJM TV newsroom where Mary Richards and Lou worked, and back at Mary’s apartment building (which launched two other spinoffs, Rhoda and Phyllis). You could put any two actors on that show together and get huge laughs, and even the occasional pathos. But its most important relationship — both creatively and sociologically — was the one between Mary and Lou. He was a familiar character type — the sort of authority figure people might describe as “crusty but benign” — but played so well that almost every comedy boss after would be compared to him. She, meanwhile, was a revolutionary for television, as a single woman far more focused on her career than finding a man. Moore was already beloved by audiences from her days on The Dick Van Dyke Show, but Mary Richards was still something new for them, and Lou’s grudging acceptance of her place in the office, and his life, made him an appealing viewer surrogate. If a man with Lou’s gruff disposition couldn’t help being impressed by Mary, then the rest of us were powerless to resist. As other characters came and went, their friendship(*) remained the foundation that made the rest of the series work

(*) Other shows might have tried pairing them off romantically after Lou got divorced a few seasons in. Instead, they remained platonic pals until the series’ penultimate episode, when Georgette Baxter suggested Mary ask Lou out after yet another date gone awry. The story ends as it should have: Mary and Lou’s first and only kiss gives both of them the giggles as they realize they’re not meant to be a couple.

Though Asner became famous for hurling zingers and withering glances, he still kept a hand in the dramatic world in which he had toiled in obscurity for so long. He won Emmys for supporting roles in two of the Seventies’ defining TV events: 1976’s Rich Man, Poor Man, which essentially kicked off the miniseries boom that would be the medium’s prestige category for the next 20 years or so; and 1977’s Roots, the national sensation about America’s shameful history of slavery. The latter role, as a slave ship captain who finds the work reprehensible but does it nonetheless, could have been played as a sop to the majority white audience watching broadcast TV at the time — one vaguely sympathetic man in a project where every other white character was outright villainous. Asner, though, looked at Captain Davies as a “good German” — a man who thinks of himself as good but goes along with evil because he’s ultimately too weak not to — making his performance in many ways more chilling than that of his co-stars playing plantation owners, overseers, and other instruments of oppression.

Roots aired a few months before The Mary Tyler Moore Show concluded. MTM co-creators James L. Brooks and Allan Burns had a deal to make another show with Asner, and these recent reminders of his dramatic bonafides no doubt influenced their decision to have him continue playing Lou Grant, but in a serious setting. Lou was fired by WJM in the MTM finale, leaving him free to go back to his first love of newspapers, as city editor of the fictional Los Angeles Tribune. This version of Lou was a bit less clumsy and voluble than the version viewers knew and loved, but he was tough and firm in the same way, and Asner provided essential gravitas to a series dealing with hot-button issues like sexual assault, gay rights, child abuse, and more. It ran for five successful seasons, and could have had more if not for Paley’s alleged distaste for Asner’s political activism. (The year before, for instance, Asner had publicly thrown his support behind striking air traffic controllers.)

Lou Grant‘s cancellation signaled the end of the improbable stardom phase of Asner’s career. He was never at a loss for work, though he often wound up in short-lived shows playing watered-down versions of Lou (a sitcom called Off the Rack; a high school drama called The Bronx Zoo). In the Nineties, he found a new side career as an in-demand voice actor, most prominently trying on a Scottish burr as the voice of aging warrior Hudson in Gargoyles. Eventually, this led to the other signature role of his career, as the heartbroken, cantankerous widower Carl Fredricksen in Pixar’s 2009 classic Up. The movie made Asner beloved by a new generation and led to even more voice work, including a reprise of Carl in Disney+’s upcoming spinoff series Dug Days, premiering later this week.

Asner kept working at such an advanced age, he told THR, because he was “just ensuring that I’ve left enough for the family.” But he very obviously loved the job, too. The Asner who played Carl didn’t feel that different from the one who first played Lou: Both claimed in their way to hate spunk, yet both were full of it. And their lovable scowls gave us years of laughter and tears.