Interview With the Vampires: Inside the Making of ‘What We Do in the Shadows’ Season 3

On a dark Toronto night in the middle of a bleak pandemic winter, the cast and crew of What We Do in the Shadows are cracking themselves up with poop jokes. In the scene being filmed, the four lead vampires of the FX mockumentary series — bickering lovers Laszlo (Matt Berry) and Nadja (Natasia Demetriou), ancient warrior Nandor (Kayvan Novak), and superhumanly boring “energy vampire” Colin Robinson (Mark Proksch) — are debating what to do with Nandor’s human familiar, Guillermo (Harvey Guillén), who recently outed himself as a vampire hunter. Guillermo is being kept in a cage in the basement of the group’s Staten Island home, and Colin Robinson has been obsessively studying the contents of Guillermo’s toilet bucket.

The actors traditionally stick to the script for the first few takes before they’re unleashed to improvise — a power even more potent than their vampire alter egos’ gifts of flight or hypnosis. On the spot, Novak has Nandor tell Colin Robinson, “You’ve been sliding to his BMs,” and any pretense of staying in character is gone. As his colleagues try to control their breathing, Novak realizes he got the phrasing wrong: “It should be ‘sliding into his BMs,’ ” he acknowledges, to even more laughter. After a few minutes, everyone remains composed enough to film several takes with the new joke.

Viewers of Shadows’ Season Three premiere (September 2nd) won’t hear the “sliding into his BMs” punchline. The vampires’ difficulty grasping the modern world is a core part of the series’ humor, and the producers ultimately decided Nandor wouldn’t get social media well enough to make that joke. This would be the best gag in a given episode of tons of contemporary sitcoms, but it’s not quite good enough to make the Shadows cut.

“This is something that often happens with us,” says Shadows writer-producer Stefani Robinson. “That’s the biggest bummer. We do a lot of laughing, and we end up having to pick one or two to keep.”

Kristen Schaal shares a laugh with Novak and Guillén on set.

Russ Martin/FX

It’s the kind of high-class problem that comes from making the funniest show on television. Based on the 2014 film of the same name — written and directed by Jemaine Clement and Taika Waititi, and centered on vampires sharing a house in the Wellington suburbs of the creators’ native New Zealand — the TV version of Shadows transposes the action (or lack of it) to the U.S. with a fresh cast. Following its March 2019 debut, the first two seasons received critical acclaim and fan adoration for a supply of jokes as inexhaustible as its vampires’ appetites for blood.

And what makes viewers howl is often only a fraction of what could. Guillén and Novak bust up while recalling an unbroken, largely improvised 22-minute take from the first season where the five characters keep missing each other as they move from room to room through the house; maybe eight seconds made it to air. Shadows showrunner Paul Simms suggests that when he and editor-director Yana Gorskaya first start looking at raw footage, “There are so many good options, we could release a second version of each episode that has the exact same story and entirely different dialogue.”

The version we get is more than enough, thankfully. In an era when too many TV comedies are just half-hour dramas with occasional jokes, Shadows is an unparalleled laugh-making machine. Every kind of humor is fair game, from the slapstick of Laszlo repeatedly injuring himself while wearing a cursed witch’s hat to the relationship antics of Nandor and Guillermo. It is a dumb show about dumb monsters, made by some of today’s smartest comedy minds.

“It immediately became one of my all-time favorite comedies I’ve ever seen on television,” says the show’s most prominent celebrity fan, Mark Hamill, who memorably guest-starred in Season Two. “Taking the mythology of vampires and burrowing down into the mundane qualities of their lives? I’m a longtime horror fan, and I just can’t praise it enough.”

Clement and Waititi, friends and frequent collaborators, originated the idea in a stage show years before the movie came into being. They played bickering vamps, with Waititi as an undead comedian whose entire act was about being a vampire and Clement a heckler who’d been following him from gig to gig for 300 years. “Then we wanted to make a film,” says Clement. “Taika wanted to make a mockumentary, and I wanted to do something about vampires, and we just put it together.”

As they were working on the movie, “a lot of people in the crew said, ‘This feels like a sitcom,’ ” Clement says, “so the idea was already there. And we had joked that it could be like Real Housewives. We could have different cities with different roommates.” (Eventually, they wound up doing exactly that, in the States with Shadows, and back home with Wellington Paranormal, an X-Files satire featuring a pair of cops from the movie.)

The film featured three male vampire roommates, while their familiar, Jackie, hung around on the periphery of the story. In expanding the idea into a series, Clement, who largely developed the TV incarnation while Waititi has focused on movies, tweaked the formula. He added a female vamp in Nadja, making sure she would be just as inane as the guys, plus Colin Robinson, who gains strength through the power of tedious office chitchat and internet trolling. Clement also realized in revisiting the film that Jackie “had the most at stake.” With the character of Guillermo, he decided to delve deeper into how a familiar would feel about his or her master.

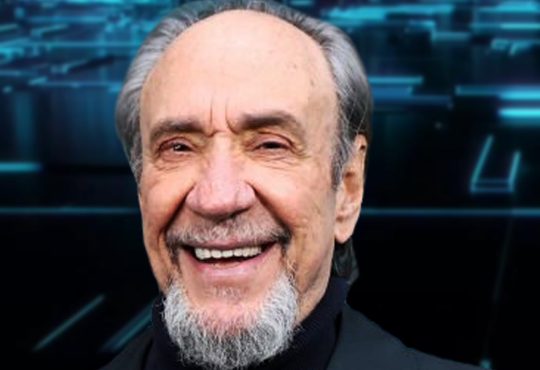

Berry, center, as Laszlo

Russ Martin/FX

Clement wrote the pompous, sexually adventurous Laszlo with Berry’s voice in his head, having long been an admirer of the English comic actor (Toast of London, The IT Crowd). The other characters really came into focus after casting. Guillermo was originally written to be an old man still holding out hope that Nandor will one day make him an immortal vampire. When the far-younger Guillén nailed his audition, the familiar became a millennial whose optimism hadn’t yet been drummed out of him. Novak, meanwhile, viewed Nandor as a blend of Clement and Waititi’s characters from the film (“He’s a warrior, like Jemaine, but he’s also a pedantic, neurotic head of the house, like Taika”), and had to figure out a comic dialect — “a slight Eastern European flat-pancake voice” that contrasts amusingly with words like “pillaging” and “killing” — as a way into the role.

Both Demetriou and her character, Nadja, have Greek ancestry, which the writers began leaning into in a way that made Clement — whose own wife (actor-playwright Miranda Manasiadis) is also of Greek descent — belatedly realize he had created a show “about being married to a Greek woman for a long time.” But Berry argues the fictional relationship is a healthy one, calling it “one of the only sort of positive things going on in the house. They are there because they want to be with each other. And they’re still as sexually active as they were on that first night.”

Those two may not be the show’s only case of true romance. Initially, Guillén struggled with the idea of Guillermo just being Nandor’s slave, but he found an emotional center to the character that made sense to him. “What I brought to that relationship is the love that he has for Nandor, and the love they have for each other,” he explains. “What kind of love is that? Is it sadomasochist, a passionate obsession, or a borderline lover-father figure? It’s all these elements, where it’s, ‘What is going on with them?’ But I like that we’re on a tightrope about it.” (Novak, for his part, says he pulls from dysfunctional relationships from his own past to inform scenes with Guillén.)

The actors don’t just take their characters’ connections seriously, but the entire ludicrous world of Shadows, an attitude crucial to making the show as riotous as it is. “I have never been interested in comedy from people that are aware that they’re being funny,” says Berry. “It’s got to look as if you don’t think what you’re doing is ridiculous in any way at all.” Proksch, who compares the show to high-concept Sixties sitcoms like The Munsters or The Addams Family, agrees: “Otherwise, it’ll just come off as a wink and a nudge, and that is never funny. It’s always embarrassing to watch that type of comedy.”

The actors find ways to goof around on set when they can — Demetriou laments that when she and Berry film talking-head interview segments in character, he often starts off by snapping, “That’s what she said!” just to make her break character — but even the improv on set is serious business. “It’s not your typical ‘yes, and’ type of comedy,” explains Proksch. “We’re actually acting in character and listening as those characters would.” Nonetheless, the ad-libbing provides all involved with so much joy that it can be hard to stop coming up with new jokes. “It’s like playing hot potato with these actors,” says Guillén, “and no one ever drops the potato.”

There is genuine danger from too much improvising or flubbing of takes, especially on a show that films at night in the dead of Toronto winter: “When you’re outside and Mark [Proksch] is in a grave and it’s minus-15, you’ve got to get through it, or someone might die,” says Demetriou, exaggerating only slightly. “This show is life-or-death in many ways.” Mostly, though, the fear is simply having too much of a good thing. FX gives its producers leeway on running time, but Simms — whose résumé includes The Larry Sanders Show, NewsRadio, and Atlanta — says he tends to get antsy around minute 23 of most sitcom episodes, and would rather leave the audience wanting more. “It is hard,” he says, “because there’s so much funny stuff. There’s just no way to fit it all in without making each episode 55 minutes long.”

Jokes that don’t advance the story, or that defy our understanding of these characters, are often the first to go. A Season Two subplot where Laszlo and Nadja perform songs at a bar originally featured a long sequence where they invited Colin Robinson onstage with them — “It was one of the most disgusting things I’ve ever seen, watching Mark Proksch move his body [to music],” Demetriou says, cackling — but Simms cut it because it conflicted with earlier scenes that had Colin rooting for his housemates to flop in front of an audience.

A lot of decisions on what jokes to keep come down to a hard-to-quantify sixth sense the creative team has developed over the years. As Stefani Robinson explains, “It’s dirty but it’s not too dirty. There’s poop jokes, but we don’t want to see the poop. There’s puns, but not too many puns. Cultural references, but not too many. It’s this weird balance we’ve had to strike.”

The biggest question, particularly for a show whose characters are as stupid as they are powerful, is figuring out when things have gotten too stupid even for Shadows. And that line seems to be shifting all the time. During Season Two, Clement pitched the idea of Laszlo fleeing town to avoid an old foe. Robinson fleshed it out to write the show’s comic high point to date: “On the Run,” where Laszlo finds himself tending bar in a small town in Pennsylvania, with only a pair of dungarees, a toothpick, and the name Jackie Daytona as his disguise. Hamill played Laszlo’s nemesis Jim the Vampire, who is completely fooled by the costume, only recognizing Laszlo when he takes the toothpick out of his mouth.

“When I read it,” Clement admits of the toothpick scene, “I said, ‘We haven’t gone this dumb before.’ ” But it played spectacularly well, as did all of the episode’s jokes about “Jackie” inspiring the local girls’ volleyball team to newfound success (all involved insist that Laszlo did not use his powers to aid them in their pursuit of a championship) and playing Robert Palmer’s “Simply Irresistible” on the bar jukebox. Another show might have consigned Jackie to a third-string subplot; Shadows made him the centerpiece of a whole episode.

Simms compares Jackie Daytona’s genesis to his days writing with Clement and Bret McKenzie on the HBO musical-comedy Flight of the Conchords. “Those episodes often started out from the songs they had,” he says, “which is a completely backwards way of working: ‘How do we build an episode where this song makes sense here?’ That’s how it’ll be with Jemaine: ‘I thought of a really funny scene, and that’s how you get there.’ It violates everything I would tell anyone about how to structure a story. But on a show this silly, we find a way to make it work.”

The cast and crew were largely awestruck by the presence of Luke Skywalker himself. Novak was so nervous to talk to Hamill that he sent Guillén over in his stead, only to feel jealous when the two quickly hit it off without him. But it turned out that Hamill was just as giddy to meet everyone on Team Shadows. He’d become a huge fan of the whole franchise after his kids first showed him the movie, and encouraged his Twitter followers to watch Season One because every new show he likes gets canceled quickly, and he wanted Shadows to avoid the same fate. (Hamill needn’t have worried: While the show started out as a solid ratings performer for FX, its overall viewership actually jumped 100 percent in its second year, which basically doesn’t happen anymore. Season Four goes into production this fall.)

“Out of all the people I’ve met, even at Comic-Con, none of them was as excited about the show as Mark Hamill,” says Clement. “One time, I was at Skywalker Ranch, and they have a lightsaber there. And I was so excited to see this lightsaber. Our costume designer, Amanda Neale, gave Mark the ring I wore in the film, and he was as excited to have that as I was about the lightsaber, which blew me away.”

For Hamill, the hardest part was not laughing constantly while surrounded by his comic heroes. “Matt Berry ad-libs like crazy,” he says. “You have to stay in character, because my character doesn’t think he’s funny, but Mark Hamill thinks he’s hilarious.”

Demetriou, center, gets a touch-up.

Russ Martin/FX

Season Two debuted in the early days of the pandemic, which only made the show’s brand of unapologetic goofiness even more appealing. As the cast and crew reassembled in Toronto at the start of this year to film new episodes under strict Covid protocols (this story was reported entirely via Zoom and phone), the most important thing on everyone’s mind, Demetriou says, was, “How can we make this scene the funniest it can be, how stupid can we take this? That’s a rare thing at the moment. Because everything’s quite serious in the world.”

Season Three deals with the fallout from the vampires discovering Guillermo’s secret and the power vacuum he created by killing so many elite vampires, plus Colin Robinson exploring his own cloudy origins. What it will not deal with is the pandemic, which is far too weighty a subject for this show. But Shadows’ premise turns out to be oddly perfect for a world emerging from quarantine. “It’s always about creating situations where they have to go out into a world they’re not familiar with,” says Simms. “They haven’t had to interact with it, and they just sat around doing nothing.” For as much havoc as Laszlo and friends wreak upon the neighborhood around them, he and his housemates are almost performing a public service, both for the people who watch their misadventures and the people who make them.

“I hear this all the time from friends who watch the show, especially when Season Two came out during the pandemic,” says Robinson. “It ended up being a light for some people. It was a way to detach from more difficult things that were happening in the world and watch something that felt like it was purely silly and comedic and comforting in a very specific way.”

Not bad for a project that began with Taika Waititi in a theater telling corny vampire jokes like, “I just flew in from Transylvania — boy, are my arms tired!” What We Do in the Shadows has gotten (slightly) more sophisticated since then, but the end goal is the same: Make the audience laugh till it hurts, then, like Guillermo, beg for more pain.