The Oral History of ‘WandaVision’

It was the monoculture all along. Marvel’s WandaVision debuted on Disney+ on January 16th, timed perfectly for a pandemic-pummeled nation fresh from an assault on its Capitol so outlandish it could’ve been pulled from MCU outtakes. WandaVision was a turducken of cultural comfort food, a loving tribute to sitcom history with supernatural mystery and superheroics bubbling underneath: “a combination of Nick at Nite and Marvel,” in the words of series director Matt Shakman, all of it driven by themes of grief and loss that also fit its era all too well.

With Elizabeth Olsen and Paul Bettany reprising their movie roles as Wanda Maximoff and Vision, fiction’s only witch-synthezoid couple, the show was also the first Marvel Studios TV venture to truly connect to its culture-conquering movies (not to mention the first Marvel project after a lengthy break, since Spider-Man: Far From Home in 2019).

In a major vindication of Disney’s retro, anti-Netflix, once-a-week release schedule, WandaVision topped streaming charts, which, in a stay-at-home-and-stream moment, made it feel like everyone was watching. In the process, it even spawned a hit song of sorts, with “Agatha All Along,” the theme for the show’s villain, Kathryn Hahn’s brassy Agatha Harkness. Here’s a look back at how they pulled it all off.

In 1964, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby created Wanda Maximoff, known from the start in the comic books as the Scarlet Witch. Originally, she was a sort-of villain in the X-Men comics, and later embraced heroism and joined the Avengers. By 1968, Lee’s protégé, Roy Thomas, was writing The Avengers, and needed more members for the team. Thomas (with artist John Buscema) came up with the Vision, loosely inspired by a 1940s character with the same name, and soon began developing a Scarlet Witch-Vision romance.

Roy Thomas: Stan said, “I want the new Avenger to be an android.” So I made up a new Vision, and made him an android. I swiped the diamond symbol on his chest from an old 1940s character I liked called Spy Smasher. John [Buscema] added the jewel on his forehead, which was initially just a design element. I guess in the movies, they made it an Infinity Stone. Somehow it was just natural to have Vision and Scarlet Witch attracted to each other. The whole idea was he was supposed to be a very human robot — in his second appearance I had him shedding tears. So it made sense for him to have a romance. But we didn’t have a lot of women around to have a romance with. Black Widow was taken. The Wasp was taken. And there was the Scarlet Witch, the extra girl at the dance! It worked out well, but it was pretty much luck that it happened. A romance of convenience.

In the comic books over the years, the Scarlet Witch became more and more powerful, and developed a complex relationship with a witch named Agatha Harkness, who tutored her in magic. In the Eighties, Scarlet Witch and Vision tried to settle down in suburbia, and had kids who later turned out to be mystical creations with souls borrowed from a demon. (It happens.) In 2016, the comic-book Vision returned to the suburbs, building a different, robotic family, in a surreal series from writer Tom King and artist Gabriel Hernandez Walta.

In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Vision, played by Paul Bettany, and Wanda Maximoff, played by Elizabeth Olsen, both debuted in 2015’s Avengers: Age of Ultron. Bettany had earlier started his MCU life as a glorified Siri, the disembodied voice of Tony Stark’s digital assistant, Jarvis — he first pops up delivering a weather report in 2008’s Iron Man.

Despite limited screen time in the films, Olsen and Bettany managed to make Wanda and Vision’s love story feel real.

Paul Bettany: You’re helped in that endeavor by the fact that there’s nobody else swimming in that lane. And tonally, the films needed that. They need a beating heart of a romantic story. [The filmmakers] didn’t want to give too much screen time to it, but they still wanted it to pack a punch.

At the same time, though, the movies moved too fast to linger on Wanda’s emotions about it all. Her story was one of unrelenting loss and trauma: she was orphaned as a child; her brother Pietro (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) died in Age of Ultron; she was responsible for the accidental deaths of civilians in Captain America: Civil War; and then Vision died (twice, technically) in Avengers: Infinity War.

Kevin Feige, Marvel Studios President: Post-Endgame, we knew we wanted to see more of Vision, [even though he was] dead at that point, and see more of Lizzie’s character. Comics fans knew forever that she’s an amazing character with boundless potential, both in terms of her powers and the conflicts and drama. We wanted to delve into the Scarlet Witch, which was a name that we’d never said in her multiple, multiple appearances — superhero names don’t always come up in the films.

And the [2016] Vision comics series was on my desk for a long time. I just loved the white picket fence, the mailbox that says “Visions” on it, and the image of Vision and his android family in this suburban home. At the time, we were under a lot of pressure finishing Infinity War and Endgame. And while we were in Atlanta shooting those two films together, there was a cable channel in the hotel where I was staying that every morning had Leave it to Beaver and My Three Sons. Rather than watching the news in the morning, I just had that on.

I found great comfort in old sitcoms. I found it so soothing. The way those people had a problem and got to figure it out, man, you think “everything will be OK today,” as we head out to whatever production issue we were having. I also started showing my kids The Brady Bunch. So I started to become fascinated with the idea of being able to play with that genre in a way that could both subvert what we do at Marvel and subvert what those shows were.

Around that same time, [then-CEO of Disney] Bob Iger told us about Disney+, and said, “We want Marvel Studios to start doing programs.” And I thought, “Oh, so now I have an opportunity to not just have this stuff rattle around my head. We could actually turn this into something.” We pitched it to Paul and Lizzie. We started working with a creative exec at Marvel named Brian Chapek, and then [executive producer] Mary Livanos took it on, just trying to flesh it out: “Could this be something?” Then Mary brought in [head writer] Jac Schaeffer, and we hired [director] Matt Shakman, and the rest is history.

But it really started with this idea of the love of television and the comfort that television brings, which is kind of a false comfort, we all have to admit. But in the show, it’s a way of dealing with grief. When you go down the line and explain to somebody what Wanda has been through, it is as traumatic as it gets, in a way that I think people don’t quite understand. You know, the death of Pietro, it’s just one of 1,000 things that happens in Age of Ultron. The death of Vision is the culminating event of Infinity War, but then half the population of reality disappears. So there’s always other things happening in each individual movie, but when you just look from this woman’s point of view, how does that grief manifest itself?

Elizabeth Olsen: What I was told at the beginning was that Kevin thought there would be a way to have Wanda transform the reality she was in into a sitcom. I kept thinking about one of the bits in the Twilight Zone movie, with the boy who has the bunny rabbit come out of the TV. So in my head, what we were making was this twisted relationship with television. It was a pretty solid start [laughs], from his concept to what we ended up making.

Mary Livanos, co-executive producer: I came on the project in the summer of 2018. I tried to read all the comics available. I went through all these old suburban family sitcoms, studied the episode setups, studied episode titles, watched everything that we could. Once Jac was on board, everything started to solidify very quickly.

Jac Schaeffer: Our early conversations were about Wanda not having time to process what’s happened to her in the movies, having to continually just move forward into these action-packed scenarios. We talked about how isolated she is, that she loses her brother and then moves to a new country, and then makes this horrendous mistake in Lagos. And then she loses Vision, the one connection she had. My original pitch was mapped out to the stages of grief. And that would be tied to the sitcoms and tied to her performance and her motivation and a given episode. So the finale was always, like, ramping toward acceptance.

In my original pitch, there was the idea that we would start in the sitcoms, that we would have several episodes in a row that were very entrenched in the world and the tone, but that the truth of the scenario would sort of be fraying at the edges… And the feeling of “very special episodes” was something I was chasing from Day One. With a sitcom, with comedies, the creators make a pact with the audience that you’re in a safe space. Everything’s going to be resolved. And these episodes break from that and violate that agreement. I remember them in my body. I remember the sick feeling that I would have.

The one I always go to in my mind is when Carol Seaver’s boyfriend died on Growing Pains — it was Matthew Perry, actually, that played him… And it was so shocking and wrong and such a betrayal of the agreement that the show has with the audience. I was like, “That’s what I want to do! I want to chase that feeling with intention. I want to violate our agreement with the audience and give them that freaky, sick feeling, because that’s what Wanda is experiencing.”

Olsen: I felt like it was the first time a writer really understood the 360 of this woman’s inner and exterior world. For instance, I usually have to tell writers, “Just remember that English isn’t Wanda’s first language.” So when she is not in sitcom land, there has to be a different kind of rhythm to how she says things. And Jac already understood that.

Wanda is from the fictional country of Sokovia, but as a joke in WandaVision acknowledges, her Eastern European accent had been disappearing in the movies, and vanishes entirely in the sitcom world.

Olsen: So that started with Civil War. The Russos [directors Anthony and Joseph Russo] said, “Can she just have a softer accent, because she’s been in America, and has to have been speaking English more.” So I was like, sure. I do have to say that in [Wanda’s next appearance, in 2022’s] Dr. Strange [in the Multiverse of Madness], after the experience she has in WandaVision, she goes back to an accent that’s more true to her. Now that I feel a little bit more ownership of the character, I feel like she does retreat back to having this more honest expression. The sitcom part was totally different, because she’s trying to hold on to an American sitcom world and play the part the best she can.

Matt Shakman, director: One of the first things I talked to Kevin Feige about when I was coming on board was whether one director could do all the episodes. And I said, “Yes, of course, absolutely.” I am really glad that I did. But also some days it was very hard, and maybe I shouldn’t have been so quick to say yes. He wanted to run it the way that they had been running their films, where they had a single filmmaker that they worked with. But at the same time, it was similar in some ways to a more traditional television process, because they had hired Jac as the head writer. It was going to be this pretty interesting experiment with style and structure that was going to start in a sitcom world. If you’re gonna play around with different tones and styles and genres, you have to have a good reason to do it. And the spine of this show was such a strong emotional one, and the thematics were so clean, that it allowed us to do some pretty amazing, wacky stuff.

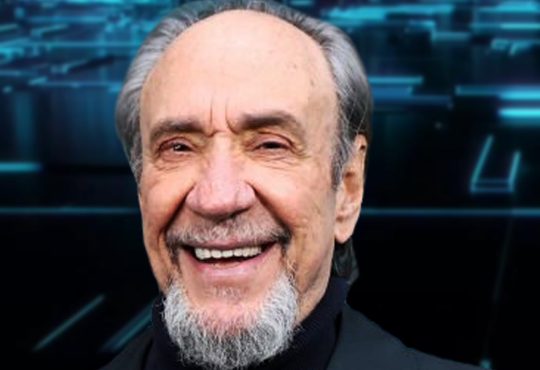

Bettany (seated at desk) and Shakman (crouching) on the set

Chuck Zlotnick/Marvel Studios

Schaeffer: Moving through decades really ended up dovetailing so beautifully with the grief arc. We start in the 1950s, postwar sitcoms, where it’s all about optimism, and it’s all about appearances, and everything is upbeat, and it feels like possibilities are limitless. It’s also very contrived and constructed and performative. And then as we move forward, things get looser and more authentic and more sincere, and then they get into the Malcolm in the Middle era, and the Nineties and 2000s, where things get downright rough around the edges. Then when we got to the era of confessional sitcoms, of breaking the fourth wall and sitting down for interviews, which was so perfect for the depression piece. We played into the comedy of her wardrobe and eating cereal and watching TV and not wanting to take care of your kids, but the actual spine of it is genuine depression.

Olsen: When I learned that it was Fifties, Sixties, Seventies, and that was how they’re breaking down the episodes, I was thinking, “This is going to be so hard!” For the Fifties and Sixties, I drew on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, The Dick Van Dyke Show, Bewitched. For the Seventies, I was kind of going on instinct at that point, and one of my favorite references in the world is [the 1996 movie] A Very Brady Sequel, not the actual Brady Bunch.

Feige came up with the title of the show — which is also the name of the show-within-the-show that Wanda creates — thanks to an unexpected inspiration.

Feige: I didn’t want to call the show Wanda and Vision or The Scarlet Witch and Vision. I was at the AFI [American Film Institute] luncheon in 2018 and I remember looking at the board where it listed the top 10 films and seeing BlacKkKlansman. I remember thinking, “How cool is that? They just mushed those two words together and the audience just accepts that as a title.” So I thank Spike Lee for making BlacKkKlansman. I know that’s the weirdest connection ever, but that’s how it came about.

The central premise of the show is that Wanda has hexed an entire New Jersey town into an ever-shifting sitcom world — and is actually broadcasting a show over TV airwaves, for reasons never explicitly stated.

Schaeffer: In my mind, Wanda is broadcasting for two reasons. One, she’s curating her experience. She is creating the full picture of her idealized world. So she’s editing and adding a score and adding commercials, and she’s making the completed piece that is verification of her perfect life. Second to that, I think she’s looking for a witness. It’s a call for help. It’s reaching out. The broadcast ends and cuts out after the hex expansion at the end of Episode Seven. And that’s because she’s done with the outside world.

Episode One was a radical challenge. They shot it in front of an actual live studio audience, and used the oldest of old-school special effects — wires to make objects float — to pull off Wanda’s powers live on camera.

Shakman: My respect for the filmmakers who made I Dream of Jeannie and Bewitched increased dramatically throughout the process. Doing stuff on a wire can actually be a lot harder than doing contemporary stuff in front of green screens. It’s like remembering how to play a forgotten musical instrument. But we were very, very lucky because Dan Sudick, who was our special effects coordinator, and who worked on many Marvel movies, came up under the people who did Bewitched and I Dream of Jeannie. So he actually had direct experience with that style of work, working under the people who had done it. We had to train a bunch of his technicians in a new art; they had to hang on the rafters with monofilament lines and hide under kitchen islands and pop out of cabinets and do all sorts of crazy stuff. But it was a great deal of fun.

Feige and Shakman also had lunch at Disneyland with Dick Van Dyke, whose show was a model for Episode One.

Shakman: Kevin Feige and I had lunch with him at [the members-only] Club 33, above Pirates of the Caribbean. So it was the most amazing Disney lunch of all time. It was hugely helpful. I wanted to talk to him about the special sauce — how do you do something that’s grounded and silly at the same time? — and there’s really no one better at that than Dick Van Dyke, so hearing his wisdom was really helpful in terms of setting tone. He said something very simple that I will take with me the rest of my life, something I think that Carl Reiner had actually said, which is: If it can’t happen in real life, it can’t happen on our show.

Bettany: I hated the idea of a live show at first. I really pushed back. I really tried to squash that idea. I hadn’t been in front of an audience in 25 years or something, now I’m gonna be a robot in a 1950s sitcom? Are you kidding? But Matt, who was so smart about so many things, really was right about how it would give you that performative quality that shows during that time had. It felt like there was an audience in their bedroom, and I’m not sure we would have been clever enough to get that without just actually having an audience. And in the end I just loved it, because I’m super-shallow and everybody was laughing, and it gives you such a buzz.

The first hint of the darker twists awaiting came in the creepy scene where Mr. Hart (Fred Melamed) begins to choke at dinner.

Shakman: One of the things I talked about a lot was how to transition from that multicam, proscenium, Dick Van Dyke, I Love Lucy-style of shooting into something that would be much more psychologically interesting, and would touch that undercurrent of dread that’s running and throughout the whole show. There are a lot of moments like that in the show. We talk about them as Get Out moments, where you can see beneath the veneer.

Olsen: The “why” of the changes from each sitcom to the next is that the moment something goes wrong, the moment something isn’t going as planned in the construct of the rules of this decade, she has to change the decade, because it’s not working here. And it’s subconscious at first, until it becomes a choice that she makes.

Schaeffer: That idea was in my original pitch, but it was far too literal. In the beginning, we were thinking we would explore the issue of xenophobia, which is very present in some of the older comics. So the mechanism that would propel them into the next episode was a little bit more dramatic, almost cataclysmic. There’s the couple in the comics that make their lives kind of hard; they’re neighbors who like them because he’s a robot, and she’s Sokovian. And so the world would kind of fall apart, and those people would turn a little bit aggressive, and Wanda and Vision would be chased out of town. So the idea of “it’s not going her way, and that’s why she moves forward,” was far more literalized in the beginning. And then it became increasingly subtle and creepier and more based in psychological horror as we moved forward.

The show shot at more than triple the pace of a typical Marvel film.

Olsen: A lot of my memories of it have to do with, like, total chaos and exhaustion. Usually on a Marvel movie, you shoot like a page to two pages a day [of script]. And on our show, we’re shooting seven. The speed of everything was just a totally different level. A lot of chaos started to happen. Paul and I were doing reshoots during Covid of one of the last scenes in the Sixties. We had no time to film the scene that happens backstage right after we do the magic show — I’m asking him what’s going on and he tells me he swallowed gum and that whole bit. It was so hammy and so ridiculous and we just could not hold it together. We could not stop laughing.

Bettany was particularly nervous about having to act drunk as the Vision in that sequence in Episode Two, after he swallows a piece of gum.

Bettany: We kept putting it off. It was an exterior, so we were going to shoot it last in L.A., and we knew we weren’t gonna get to that for four months, after we shot the interiors. And then Covid happened and eight months passed. When you start rewatching The Dick Van Dyke Show, his skill is extraordinary, and when he does drunk acting in it, it’s amazing and balletic and so over-the-top. And I just went, “Oh my god. I have no idea how I’m going to do it.” Then the day happened, and I just was like, “Well, I guess I’m gonna go down swinging.” There was some Dudley Moore, some [British comedian] Rik Mayall, some John Cleese in there. I trusted Matt to tell me when it was too much.

It was really funny because there was one time where Lizzie and I were sneaking out after the magic show went wrong. And then Matt came over and Lizzie was like, “Oh, God. He’s finally gonna come and tell us we’ve done too much.” He came over and said, “I love the sneaking. Could you also do a double take?” [Laughs.] I’m surprised we don’t have a spit take in that show.

The idea of using the comic-book character Agatha Harkness, who would initially be disguised as a neighbor named Agnes, came early on, as did the series-making idea of casting Kathryn Hahn.

Livanos: Agatha is an awesome character from the comics. She’s really central to Wanda’s evolution as a witch. We wanted someone to be messing with Wanda, to be making Wanda emotionally second-guess herself and to propel Wanda into the world of magic. Agatha felt like the best, coolest option. Once we knew we had Kathryn Hahn, I mean — the character was designed to be brassy from the get-go, but my gosh, Kathryn adds a whole new depth that I don’t think we could ever have imagined. Casting her was a literal miracle. We were banging our heads against the wall trying to figure out who could possibly be Agatha, and Kathryn came in just for a general meeting with Marvel. I think it was the fastest turnaround from a regular meeting into casting of our prime villain that Marvel has ever had.

Kathryn Hahn: I just love the idea of a dangerous woman. The word “witch” has such a connotation. Just historically speaking, it’s been a way to categorize or shut up a woman that is loud or unexplainable or complicated or dangerous or messy, or whatever it is. Agatha is an ancient and very, very powerful witch. She can be a mentor and be an antagonist, and be 100 years old and still look kind of fabulous! Mary Livanos made a binder, and inside it was basically every single time that Agatha has appeared in the comics, since [1970]. So I had something really concrete to start with. And of course the show is a lot of the comics smushed together, metaphorically. I was definitely able to use those backbones.

Wanda (Olsen) uses her powers to create a new Vision.

Courtesy of Marvel Studios

More than any character on the show, Agatha, who first appears in the guise of a neighbor named Agnes, is always operating on more than one level. When she asks Wanda questions — “So, what’s a single gal like you doing rattling around this big house?” — she’s actually fishing for information on the magical event she knew Wanda perpetrated in the fictional town of Westview, New Jersey.

Hahn: It would be fun to go back and watch from the beginning again, because it’s all in there, all those questions and queries. We knew how to layer in all those different levels and still play on the top of it. Agatha certainly knew a lot of what was going on, and she lingered in the sitcom world longer than she had anticipated, just because she started having a good time. But it was a fine line. You had to really play in the world, because you didn’t want to tip anything to the audience, who are very savvy anyway, especially the people that know Marvel really, really well.

Olsen: I felt like Kathryn and I got to tap into this child-performer space, where we could perform without fear of coming across as too much or unrealistic. It was really freeing. I’ve never done a sitcom. The closest thing I’ve ever done was a screwball comedy class in college. And while I was in that class, I was kind of frustrated to be doing it, like, “No one does this anymore.” Kathryn and I had this amazing thing where we still had the same vocal warm-up, no matter what the decade was, until we were out of sitcom land. Because people in the sitcoms in those decades used so much more of their vocal range. And we would always warm up just going [campily, almost singing], “why, why, why, my, my.” That shoved us into sitcom land.

Hahn: Courtney Young was our amazing dialect coach, and she would say, with women in the Fifties and Sixties, you can hear vocally the change in the way that women are allowed to exist and take up space and make noise. Women were speaking in such higher pitches, and always kind of ended with question marks. There was never like a period. Like, they were never allowed to have an opinion, so they always ended their sentences on this [singing] “oh?” It was just so wild.

Schaeffer: In the original conception, Agatha’s character was more in the mentor and magic-expert space. One of the things that never changed was that in the finale, Wanda would have to say goodbye to Vision. In my original notion of it, that goodbye was like a final binding spell that she had to do. And it was tied to a spell that Agatha had taught her early in the series, where a gravy tureen had shattered, and Agatha taught her this very basic binding spell. In the end, what she has to do is integrate her trauma, and she has to bind Vision back to herself with that spell. Agatha ended up becoming more of an antagonistic force, because we needed that in the series.

There was more dissection of the idea of chaos magic [the source of Wanda’s powers] in the [writers] room, too. When we hired Matt, there was a long period where we were trying to design a chaos dimension, which ended up not serving us and wasn’t necessary.

Hahn: The relationship is complicated to me. It is kind of like an Amadeus-Salieri relationship. Even though she does come across as an antagonist in this series, I think there’s a reason Wanda was able to give up so much of her personal history to this woman. I’d like to believe there was a connection.

Olsen gave Hahn some tips on how to fly in a harness and other MCU-specific acting challenges.

Hahn: It was mostly about trying not to overthink it and trying to keep it on a scale of person-to-person. And there was a lot of discussion of how to tip your pelvis while you’re in a certain harness so that you wouldn’t tweak your back. Also, I had to really carefully plot out my bathroom trips because it was a 45-minute process. I’m not kidding you. With the fingernails, the costume, with everything, to go to the bathroom took about 45 minutes. I have such gratitude to Beth, my wardrobe assistant. We’re in the 100-degree heat with this person trying to lift up gazillions of skirts.

Another early addition to WandaVision was an adult version of Monica Rambeau, first seen in the MCU as a child, the daughter of Carol Danvers’ best friend, in 2019’s Captain Marvel (which was set in the Nineties). In the comics, Rambeau was one of Marvel’s first black female superheroes, first using the name Captain Marvel herself and then becoming Spectrum.

Livanos: The notion that Monica Rambeau would be a part of the story was an early discovery in the writers room. The idea that Monica was an especially empathetic character was intriguing to us, and it presented the opportunity to introduce her as a hero in her own right in this show.

Actress Teyonah Parris, who had appeared in 2014’s Dear White People and on Mad Men, knew about Rambeau character even before the character appeared in Captain Marvel, thanks to tweets from fans suggesting she’d be perfect in the part.

Teyonah Parris: I looked her up, and I was like, “Wow, she is amazing, and has a really rich history in the comics.” But to be honest, she’s a black woman. So the likelihood that we would see her in the movies, in my opinion, at that time, was very slim… Then she showed up as a young girl in Captain Marvel. I thought, “Oh, my gosh, wow. That’s the character that the fans have been talking about.” And what’s weird and crazy is that watching the movie Captain Marvel, it never dawned on me that she might grow and they might have to cast her as an adult… But essentially, it came back around, and I auditioned for a Marvel role, and then I found out it was Monica Rambeau. That was a very surreal feeling, because I’ve always wanted to be in the MCU.

I definitely went in not knowing much of anything until I sat down with Matt Shakman and Jac Schaeffer and Mary Livanos in L.A. in their war room for the show, maybe two months after I got the job. I saw the storyboards on the wall, and I see my face pre-vized [digitally pre-visualized] into images of the action stuff — that moment when Monica is going through the hex, they had that storyboarded with my face. And it was just so overwhelming that I remember bursting into tears in that room in front of them. They got me tissues, and I’m in the hall walking around, and all of a sudden I see Kevin Feige, and he’s like, “What are you doing out here?” And I’m trying to compose myself.

Where did the tears come from? I was thinking about my parents, their love, their encouragement, the low times where maybe you don’t book anything for a year and a half and you have no money. So I was just feeling the support and the love, and how there were so many people that got me to this moment. This was an actual dream, to be a Marvel superhero, and I’m here. I think it was also knowing that to be a woman and to be a black woman in this superhero space, it’s not very often we get to have that. So now I get to add to that narrative, to that representation, and to be a part of the imagery I wanted to see more of as a young girl.

When Monica is sucked into Wanda’s TV-show reality, transforming into a neighbor named Geraldine, Parris had a specific approach to the character, particularly in the Seventies episode.

Parris: I felt that Monica would pull from someone like a Willona from Good Times. And if you’re going to go through the decades of American sitcoms, and you have people of color, you have to acknowledge where they were not in that space. That character didn’t necessarily belong in that Brady Bunch space. And then you have Geraldine, who doesn’t belong in Wanda’s fake world.

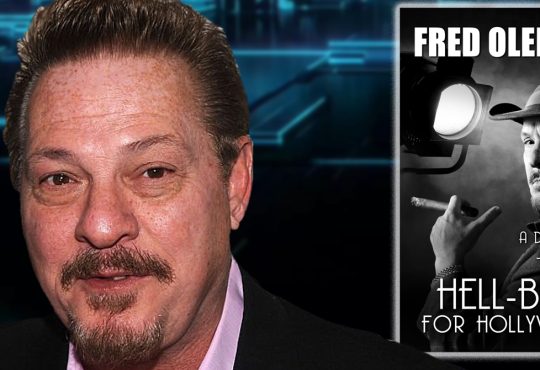

Olsen and Hahn

Courtesy of Marvel Studios

Introducing Evan Peters, who played a version of Wanda’s brother Pietro in the separate, 20th Century Fox-produced universe of the X-Men movies, to appear as what seemed to be a revived, “recast” version of her brother (played by Aaron Taylor-Johnson in the MCU), drove fans wild — probably too wild. Suddenly, online speculation suggested Hugh Jackman might appear as Wolverine or Ian McKellen as Magneto or Patrick Stewart as Professor Charles Xavier. It didn’t help that Bettany jokingly said he would soon be working on the show with an actor he’d always admired (he was referring to himself, playing the white-colored, emotionless version of the Vision).

Bettany: I did not know what I was doing [when I said that]. Felt slightly stupid about it. Initially, I was like, that’s a funny joke! And then I started to get frightened because I was like, fuck, actually, it’s a great idea. I want Patrick Stewart to be in it now! And it’s gonna just be me.

Schaeffer: I was never interested in driving anyone insane. I wanted to blow people’s minds. Mary and I had the idea really early on, and my connection to it was the meta element, that we’re making a show that’s about television, we’re using that language of “recasting.” But yeah, it did seem to escalate. The scope of the show is surprisingly small, which was one of the reasons I felt suited to it, so when people started theorizing about Magneto and all these other things, I kept being like, “No, look at the show — like, the show is small! You all have been deprived of Marvel content for a year, so your brains are going to these stratospheric places, but the actual show is not making that promise.” At the end of the day this will continue to be about Wanda and her journey.

WandaVision’s most unexpected pleasures came from bringing together Jimmy Woo, the F.B.I. agent last seen in Ant-Man and the Wasp (Randall Park), and the sardonic intern Darcy Lewis (Kat Dennings), who popped up in 2013’s Thor: The Dark World (and had since, the writers decided, become a scientist with a Ph.D.).

Feige: A lot of it came down to, we needed a character with a science background and a character with a law enforcement background to be on the outside of the hex. There were always discussions of who that would be. But if you’re gonna cut away from WandaVision, you’ve got to have some pretty great, fascinating characters. So it was amazing to say, well, gosh, Darcy Lewis, wouldn’t she be fun to come back to? Do you think Kat would do it? Randall Park is amazing. We’d watch him do anything. Do you think he would do it?

Schaeffer: In earlier drafts, there was more of Darcy before she gets to the hex. And as the project coalesced it made more sense to keep everything base-centric, except for S.W.O.R.D. headquarters. So we lost some of that other stuff. But it was really fun to write for Kat and to see a little bit more [of] what’s been going on with Darcy. We had this idea that Darcy didn’t blip, but her grandmother did. And now her grandmother’s back and Darcy had pawned her old TV, so she has to go get the TV back. And when she plugs it in, Episode One pops up, and that’s how the broadcast is discovered. It was silly, it was too much of a detour. But that writing infused all the later writing for Darcy. We also jumped all over the opportunity to have her be a Ph.D. now. That was just delightful to write.

Kat Dennings: I don’t usually get to play the smartest person in the room, in life or in casting, so I totally enjoyed that. There’s something really fun about correcting somebody who doesn’t address you as “Doctor,” if you’re a doctor.

Dennings’ first appearance on the show is actually at the beginning of Episode One, when you see her hands taking notes in front of a monitor showing Wanda’s broadcast.

Dennings: Yes, that is my hand! And it’s so funny, only my mom spotted that, and one of my friends. It had been eight years since I was in the MCU, so I never expected to come back. I said yes, obviously, before they could say three sentences. “I’ll do it!”

Park, who’s attached enough to Jimmy Woo to have the comic book where the character first appeared on his wall, first shows up in WandaVision in Episode Two, as a disembodied voice on the radio, asking “Who’s doing this to you, Wanda?” A surprising number of viewers figured out who was talking.

Randall Park: I have a pretty recognizable voice, I guess. I’ve been recognized wearing a mask on the street when I start talking.

Both Jimmy Woo and Darcy are direct audience surrogates, literally watching the WandaVision show on TV.

Park: It was fun to do those scenes where we were staring at all those old TVs. We were actually watching a blank screen with some green tape on it for post-production purposes.

Dennings: We didn’t really know what we were watching, but I think it ended up helping the performances because we both were clueless as to what was going on, just like the characters were… It was so gratifying to see that all happen, ’cause Darcy says, “I’ve been watching WandaVision.” And I didn’t think of it at all when I was saying the line. But when you see it, it’s like, oh my God, this is so much fun. It couldn’t be more meta. It’s her favorite show and she gets to go in it.

Park particularly enjoyed Woo’s first action scene, where he gets to throw a punch.

Park: I learned how much goes into an action sequence at Marvel. They have the greatest stunt coordinators. And they have, at Pinewood Studios, a gym and a facility where you work out the fight scenes. It was weeks and weeks of choreography. So by the time we get on set, it’s kind of automatic. That was really thrilling for me.

Mastering Ant-Man’s card trick was another highlight.

Park: I love that they reference the card tricks [from Ant-Man and the Wasp]. It also was a sign of his evolution that he’d gotten good at some of these tricks. It’s a subtle thing, and a silly thing, but it was revealing of character that he was fascinated by those card tricks and really wanted to learn… My hope is that Jimmy Woo will come back. I just love this character and I could play him forever.

One mystery lingers: Woo is said to have arrived at Westview in search of a missing person. That person’s identity is never mentioned in the show — and it may still have significance.

Schaeffer: I think it’s great to wonder about that. There’s not a lot I can say about it. I wish I could say something printable. But I love that people are speculating about that.

One of the show’s innovations was to introduce a memorable series of in-universe commercials.

Shakman: Well, we were creating TV shows, so we always knew we wanted to have commercials. So then the question was, well, what are the commercials? We talked about whether we wanted to have multiple commercials, but ultimately we have so much narrative to juggle that we really only had room for one commercial per show. And we wanted it to be an opportunity to have some of the larger thematics of the show trickling in, and also some of the history of Wanda — that they were a way for her unconscious to be manifesting. To that end, we picked the same two actors, two Westview residents, who had been assigned a job. They were just cast as the commercial people. Wanda put them in every single commercial, and the kids were also the same.

Schaeffer: There was a version of the commercials where it was Dr. Strange trying to reach out to her, that he was actually behind the commercials, and we moved off of that idea.

Feige: I haven’t talked about this before, but we had a deal with Benedict [Cumberbatch] to pop up at the end of WandaVision, or somewhere in WandaVision. Because we knew we wanted to connect them [Wanda’s next appearance is in the second Dr. Strange movie, next year’s Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness], and wouldn’t it be great. But as we worked on the show, and on the movie, we realized there was no reason to really do that.

Schaeffer: One of my favorite ideas was that in the Nexus commercial [in Episode Seven], it would kind of be a blink-and-you-miss-it cameo, a quick image of Dr. Strange as the pharmacist in the background. I was very inspired by Fight Club, when Brad Pitt’s character is on the TV in the hotel — like, if you’re looking closely you’d see it for just a second. We were like, “The Nexus commercial is her subconscious. What if Strange is in the background and trying to reach her?” But ultimately we decided in favor of Wanda’s own story.

Everyone’s favorite was the Claymation ad in Episode Six, which warned of someone (Agatha, it turned out) trying to “snack” on Wanda’s magic. It didn’t quite fit among the other commercials’ manifestations of Wanda’s subconscious, but they kept it anyway.

Schaeffer: Kevin loved it so much, and we’d changed it in a draft, and he was like, “No, no, go back to the version where the kid withers on the beach.” So the idea of having a Claymation one was just so exciting and so right for the era. It didn’t change when we moved away from the Dr. Strange idea, so it feels like an outlier, I think.

The MCU has never been known for its original songs, but that changed with the arrival of Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez, the married songwriting team behind the indelible songs from Disney’s Frozen movies. They were tasked with coming up with a theme song for each era of Wanda’s sitcom — as well as a bonus song for the reveal of Agatha Harkness, which became “Agatha All Along.”

Kristen Anderson-Lopez: This was such a big swing.

Robert Lopez: We were so weirded out that Marvel was calling us in the first place.

So the point of a theme song is to provide continuity between episodes, but what they [were] asking us to do was to write six or seven different theme songs which would have done the opposite. We thought musically it would make sense to brand them all in some way, so we invented the four-note theme around the title. “Wanda” is such a musical word, and it sort of slides down the octave in a great way. The interval is a tritone. There’s a long tradition of the tritone in TV themes, like The Simpsons and The Jetsons.

Kristen was particularly excited about doing the Seventies version — as a kid, whenever she prayed to God in church, she’d throw in, like, “And please let The Brady Bunch be a musical episode today.”

Anderson-Lopez: So here was this chance to write a song like that. But the Eighties one was our absolute favorite one to do. My favorite song from first grade on was “Believe It or Not” from The Greatest American Hero, and I tried to flavor it a little bit with those kinds of chords.

For Episode Eight, which had a Malcolm in the Middle feel, they brought in Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna to sing a punk-inspired theme.

Lopez: She did it a zillion times, a zillion different ways. Sometimes she sang the note, sometimes she just kind of screamed it, and we tried to strike a balance of that. But she brought this authenticity to it because she’s the original goods.

Anderson-Lopez: She’s the one who wrote “Kurt Cobain smells like teen spirit” on the wall!

Hahn herself sang “Agatha All Along,” which arrives at the end of Episode Seven, after Agatha reveals her true identity to Wanda.

Hahn: When I heard the demo, I immediately thought of The Munsters, which is something that I grew up with. I was so delighted by it. They’re such geniuses, clearly, and as someone who’s been married for a long time myself, I still don’t understand the fact that they work so well together. But they wrote something so delicious. They Zoomed in, and we kind of banged it out in half an hour, and we just made each other laugh. They kept pushing. I just remember Kristen kept being like, “Let’s pretend you’re doing karaoke, and I’m just gonna say, like, ‘Pat Benatar’ or ‘Heart’ or whatever.” It was half an hour of just, like, joy.

Anderson-Lopez: A lot of that song was the bari sax. It’s this sound that forces you to get into a more fun place in yourself.

Lopez: I was just laughing the whole time. And Kathryn knew the tone of the show more than we did. She had been on the set, she knew the story. She was one of the storytellers more so than us. We knew about Agatha and Agnes, and we knew what kind of song it needed, but she knew how far it should go.

At the end of the song, Agatha gleefully confesses to the murder of Wanda and Vision’s dog, Sparky.

Hahn: I don’t know how I got away with it. My daughter is certainly mad at me. But then I had to tell her, “Listen, who knows if Sparky really existed?”

After watching the series and seeing the impact of “Agatha All Along,” Anderson-Lopez belatedly came up with one more song idea.

Anderson-Lopez: Looking back, I really wish we had pitched that when Agatha had control of the whole town, she made them do some sort of “Thriller” moment. If we had known the way the songs were going to hit, I think we would have wanted to have a big finale. But we had absolutely no idea.

Getting the right take of the moment where Agatha reveals herself (“The name’s Agatha Harkness. Lovely to finally meet you, dear.”) took some work.

Hahn: Man, we did that a bunch of times. Also, “that makes you the Scarlet Witch” [the reveal in Episode Nine] we did a bunch of times, too, just because those are two landing moments, two reveal moments. And I know Matt wanted to have a bazillion choices. And he did say before one of the takes — and it was such a good direction, I think it’s one that he ended up using — he was like, “You should just be really, truly excited about finally meeting her. After all this time, you can let go and finally ask her everything.” In the complexity of the relationship that Jac wrote, there was always a possibility, I felt, for them to have become friends. Certainly from Agatha’s point of view.

L-R: Parris as Monica Rambeau; (foreground:) Dennings as Darcy Lewis and Park as Jimmy Woo.

Marvel Studios

The flashback-heavy structure of Episode Eight, where we get a sense of the impact of Wanda’s trauma, was in Schaeffer’s original pitch.

Schaeffer: At the time, I was really enamored of [the 2018 Showtime drama] Escape at Dannemora. And that series’ second-to-last episode shows you the crimes the characters committed, after they built all this empathy and connection with these characters. So there’s this massive trick, where you see why they’re in prison, and it changes and fills in so much. So this was the sort of reverse of that. This was about building empathy for the character and understanding her mind space. And then the finale was always going to be this big MCU spectacular.

Olsen thought a lot about the scene where we finally see the moment a distraught Wanda created the sitcom world, along with the version of the Vision we see throughout the show.

Bettany: It reminded me a little bit of that job I had to do in A Beautiful Mind, where you’re the imaginary best friend. She has made him the perfect fit, and what might that mean? I’m Kelly LeBrock [in Weird Science] in this situation!

Olsen: That day was terrifying. We called it “the grief bomb.” You’re relying on that moment to build this entire show. So that feels like a lot of pressure. And it’s also an unnatural thing that you’re doing. Because I’m wired, I’m in a harness, and then I lift up and I’m floating on a wire while I’m wailing. So there’s a lot of things that just seem so unnatural to it. But it’s so funny, because in these Marvel movies, I’m always in this position, where there’s a big emotional moment while crazy things are happening. So since doing Age of Ultron, I feel like I’ve figured out how to have those kinds of big, emotional moments and not be too uncomfortable with the fact there’s, like, 300 people doing their job around me.

The most quoted (and memed, and mocked) line in WandaVision was the Vision’s take on mourning in Episode Eight: “What is grief if not love persevering?”

Bettany: We were all sitting down talking about the scene and feeling that it was not quite there yet. If I’m giving notes to a writer, I don’t like to be very prescriptive, because I think it’s not very helpful. And so my note was, “I think it needs to be delivered from an ingenue who’s working it out and going, ‘But grief has to have a purpose,’ because that way it won’t feel preachy.” And Jac found a line which was something like, “What is grief if not love surviving?” And then Jac’s assistant went, “persevering.” When Jac sent me that I was like, [claps] “We’re done! Pack up and go home!” Yeah, it was a really good line.

The biggest post-Covid change to the finale came with a rewrite of the scene where the townspeople swarm Wanda.

Schaeffer: In the episode, they kind of come at Wanda with their words, but initially there was a sequence where that was more of a fight. We moved away from that for Covid reasons, so I then had to write all that dialogue for them. And they’re all tremendous actors, so I think that was a win. Matt had these really amazing boards made where it was kind of like a zombie battle, and we were all enamored of that idea cinematically, but I think it ended up being more psychologically revelatory to hear them give voice to what their experience had been.

Olsen: It’s the first time that she recognizes the pain in that world, and I think she feels terrible for what she’s doing to these people. But that sequence was so fun to film.

Bettany: [White Vision] was something Kevin and I had talked about over the years.

Feige: It all starts with, “Wouldn’t it be cool?” That’s 90 percent of the discussions we have every day on set or in a development room. Disney Imagineering calls it “blue-skying.” I mean, we were on the set of Avengers one, talking about, “Wouldn’t it be cool if Paul Bettany could get out of the sound booth and onto the set as a character, and Jarvis could become Vision?” Because we knew all along that we had Paul Bettany do the voice of Jarvis, and he also would happen to be the greatest Vision. It was step by step.

Bettany: You do think, how can I do it and not just be a Terminator? I seem to mostly remember being very worried about getting white makeup on Lizzie [in the scene where white Vision attacks Wanda]. Our relationship together has been about me either getting purple makeup on her or white makeup on her. In that scene, I gave Matt lots of choices, sort of modulating. How much anger was there? Or how much sort of coldness? Because why would he feel animosity? He’s just got a job to do. And is he intrigued by her?

The Vision’s battle with himself is resolved when Wanda’s version of the Vision brings up the thought experiment known as the Ship of Theseus, which gets white Vision to question both of their identities. (“The Ship of Theseus” is an artifact in a museum. Over time, its planks of wood rot and are replaced with new planks. When no original plank remains, is it still the Ship of Theseus? Secondly, if those removed planks are restored and reassembled, free of the rot, is that the Ship of Theseus?)

Schaeffer: We knew that it would ultimately be a game of tic-tac-toe. I think it’s actually written in the script that it’s like [the end of] WarGames. We knew it was going to be resolved with a logic battle, and we put a pin in that. And then as we moved on, it was like, “Anyone have any ideas about what the heck this logic battle could be? How the hell do you write for an omniscient synthezoid?” It was Meghan McDonnell, who is the writer on Captain Marvel 2 [since announced as The Marvels], who stumbled upon this Ship of Theseus thing. And then Matt came up with the idea of putting it in the library, a palace of knowledge, which was genius, and having them spin and having the papers flutter. I was always afraid it would be the thing that would be kicked to the curb, but I do think it’s a lovely moment of rest and thought inside of the finale.

Bettany: My favorite meme so far has been “what is the Ship of Theseus, besides the Ship of Theseus persevering?“

Schaeffer had a sense of how she wanted to play Vision and Wanda’s goodbye from early on.

Schaeffer: There was a beauty to it. Even though it’s a goodbye, there was a coming home and an integration and an acceptance. So it just felt so clear to me that, while it was very sad and heartbreaking, it could be a peaceful experience that could stand in contrast to what Wanda and Vision had experienced in the MCU up to that point. I have always been fascinated with Paul’s performance and this notion of, “Am I a real boy?” I had his little speech in my head from the beginning of, “I’ve been these different things, what will I be next?” I did want it to feel hopeful, because as a fan I want to have my heart wrenched, but I don’t want to be dropped into the pit of an abyss. And that’s how I strive to look at life as well. There’s beauty amidst all the other things.

Wanda’s story will continue in 2022’s Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, but again, the two projects were almost linked much more directly.

Schaeffer: The plan when I came on board was that there would, at the end of the series, be a handoff, and that Dr. Strange’s participation would amount to essentially a short cameo. So early outlines had varying versions of the two of them [Wanda and Dr. Strange] kind of riding off into the sunset together. And it didn’t feel quite right. We wanted to fulfill Wanda’s agency and autonomy within this particular story. So it did feel a little tacked on. Another problem was, if Dr. Strange shows up at just the end, where was he this whole time? I did love writing variations of Dr. Strange, variations on those final beats. It was a pleasure to write for him. There were versions where she was flying past the city limits and then encountered Dr. Strange, that kind of thing.

Feige: Some people might say, “It would’ve been so cool to see Dr. Strange,” but it would have taken away from Wanda, which is what we didn’t want to do. We didn’t want the end of the show to be commoditized to go to the next movie, or, “Here’s the white guy, ‘let me show you how power works.’” That wasn’t what we wanted to say.

So that meant we had to reconceive how they meet in that movie. And now we have a better ending on WandaVision than we initially thought of, and a better storyline in Dr. Strange. And that’s usually how it works, which is to lay the chess pieces the way you want them to go in a general fashion, but always be willing and open to shifting them around to better serve each individual one.

Some version of the post-credits scene where Wanda has gone off to a peaceful retreat — while we see her astral self studying the occult book known as the Darkhold — was in the works even when Dr. Strange was in the picture, according to Schaeffer.

Schaeffer: We wanted more time to have elapsed, and that she would be somewhere isolated, somewhere where she felt protected, and on her own. Because we were trying, ultimately, to accomplish two goals. One, that she had reached some semblance of acceptance, and that she was able to be by herself comfortably; that there could be a measure of peace, and she could sit and have tea and reflect and not want to jump out of her skin and not, you know, be crying and self-medicating in any way, with her power or otherwise. And then the second goal was that what she’s learned through the course of the Westview experience, and specifically what she has learned from Agatha, would send her on this journey of wanting to know more about herself, and the Darkhold became the mechanism for that.

Critics suggested that Wanda seems to have gotten off easy for essentially enslaving a whole town, but Olsen says scenes that didn’t make the final cut made it clearer that Wanda was escaping Westview, not just leaving...

Olsen: What we filmed was that she had to get away before the people who would hold her accountable got there. And where she went is a place that no one could find her. I know that for sure. Because she knows that she is going to be held accountable, I think, and I think she has a tremendous amount of guilt, and a new amount of loss.

Benedict Cumberbatch may not have gotten to be in WandaVision, but he told Olsen on the set of the new Dr. Strange movie that he was a fan of the show.

Olsen: He had really positive things to say about how the show ended up. They showed it to him, I think, before it all aired. I didn’t really know what was happening in Dr. Strange until just before we got back to shooting [the film] during the pandemic in September. That was my first time getting to hear my role. And I was a little nervous that I wouldn’t be able to change certain things in WandaVision in order to support what’s going to happen in Dr. Strange. For any actor, that lack of control can be tough. But he said it is really this perfect journey that you watch her go through, in order to be invested in Dr. Strange, too. So that made me feel good, because I do feel that way myself. I feel we’ve managed to make it make a lot of sense.

WandaVision also made me feel more confident playing her. Working on Dr. Strange immediately after, I just feel like my instincts are right. It feels the way you want to feel all the time, which is kind of hard when you have such little screen time and everything that’s happening not on the page is in your head and not in the writer’s head. But what was really satisfying with this whole project was when Jac was pitching it to me, it was as if the the answers that I had in my head just as an actress somehow magically made it to her brain without me having to verbalize them to her.

As the show aired, its stars realized they were also fans.

Dennings: When they first explained it to me, I was like, holy shit, if this is possible, this is going to be the coolest thing I’ve ever seen, and the most unique thing that Marvel’s ever put out. And honestly, they did it. I thought it was so amazing. Like, sorry, I can say that because I’m not the lead character.

Hahn: I cried at the finale. Because I was nostalgic for the experience, which meant a surprising amount to me. It was a very deep experience for me, to be given the space to make this thing that was such a grand experiment but just happened to be about a woman’s process of grieving. I also got really choked up that the experience of watching it with my family was almost over. There’s something about that hex closing in that made me nostalgic for my kids growing up. And because so much of the show is through the sitcom lens, through this idea of family, of not wanting to let your kids go… there’s a lot to chew on. I was very moved, and I couldn’t be more proud to be a part of it. I would love to celebrate with the cast and everybody, and give them all squeezes.