The Nine Lives of ‘Law & Order’

The original Law & Order debuted in the fall of 1990, so long ago that the hot series it was scheduled against was thirtysomething, which nearly got revived last year as a show in which the kids from the original series would now be thirtysomething themselves. (Other new shows from that fall that have since in some stage of reboot, rumored or real, included The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Beverly Hills 90210, The Flash, and Parenthood.) It was so long ago that its other direct competition was a CBS movie-of-the-week franchise — not the movie-of-the-week franchise, because this was waaaaaay back in the day when many broadcast networks regularly scheduled two movies per week. The first “DUN-DUN” transition didn’t just happen in another century, but what feels like an entirely different medium.

Law & Order the mothership has been off the air for more than a decade, but Law & Order as a brand lives on to this day. Law & Order: Special Victims Unit is nearing the end of its 22nd season (two more, and counting, than its parent series got). And Law & Order: Organized Crime — which features the return of original SVU star Christopher Meloni as Elliot Stabler, nearly 10 years after he last played the role — premieres Thursday, as part of a two-hour crossover with SVU.

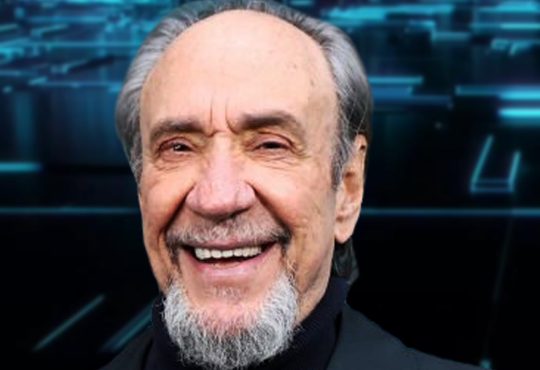

Law & Order was the brainchild of Dick Wolf, who was a copy writer for an advertising agency before writing for classic Eighties cop shows Hill Street Blues and Miami Vice. He’s always been as much a businessman as a creative type, if not more, and Law & Order was born of bottom-line concerns. In the late Eighties, the real money in television came not from a show’s original network run, but from having repeats sold into syndication, to be aired at all hours of the day and night on local TV stations around the country. But Wolf was a drama writer; networks wanted dramas to run an hour, and syndicators preferred half-hour shows. So he dreamed up a new format: a crime procedural whose episodes could be split cleanly in two, allowing a broadcast network to air them together, while a syndicator could air the first half one day and the second half the next.

As it turned out, Wolf’s Don Draper-style plan to repackage a familiar product for a new market proved unnecessary. Law & Order did eventually sell into syndication, but at its original length. Nobody cared to see the half about the police who investigate crimes separately from the half about the district attorneys who prosecute the offenders. Instead, the flexibility — and the money — came from how Wolf and his collaborators were able to expand from the original show to spinoff after spinoff.

First came 1999’s Law & Order: SVU, which had a more specific focus on crimes related to sexual assault, a reduced role for the DA’s office, and more insight into the personal lives of Stabler and Mariska Hargitay’s Olivia Benson than the mothership generally provided. Two years later, there was Law & Order: Criminal Intent, with Vincent D’Onofrio’s master interrogator Robert Goren struggling to master his inner demons. (Later seasons began a time-sharing arrangement involving Jeff Goldblum and/or original Law & Order cast member Chris Noth, but their episodes were also star vehicles.)

The franchise’s potential to expand didn’t prove infinite. In 2005, Law & Order: Trial By Jury tried to invert the prosecutors-to-cops ratio of the other spinoffs, but it couldn’t catch on, despite a cast led by Bebe Neuwirth — and, briefly, beloved L&O alum Jerry Orbach, who died after filming a handful of episodes. The following year, Wolf tried ditching the brand name altogether for Conviction, a slightly soapier drama about hot young prosecutors, fronted by Stephanie March from SVU; it lasted 13 episodes. And when NBC decided L&O was too expensive after 20 seasons, Wolf replaced it instantly with Law & Order: LA. But leaving the five boroughs proved a bridge or tunnel too far for viewers, who rejected the show despite a stacked cast featuring Alfred Molina, Terence Howard, Corey Stoll, Regina Hall, and Megan Boone.

For a decade, SVU was the last Law & Order standing (unless you count the attempt to launch a Law & Order: True Crime anthology series, whose one season, about the Menendez murders, had little in common with the franchise other than Wolf and some of his collaborators). In the meantime, Wolf built smaller empires elsewhere, including NBC’s three Chicago-set dramas (which take place in the Law & Order universe, with occasional crossover), and CBS’ rapidly-multiplying F.B.I. franchise.

But now we’re back up to two different shows under the same brand umbrella, and it’s hard not to notice that they’re built around the two original stars of SVU — a.k.a. the two characters whom L&O fans arguably know the best.

Wolf and other L&O producers, like Rene Balcer, liked to boast that there were two stars of the original series: the format, and New York City. This was perhaps yet another business-focused choice, since neither a city nor a format can demand a raise after Season Four if their Q Score gets high enough. But the original show mostly stuck to that no-nonsense brief. There was one season, the sixth, that began offering greater hints of what our heroes did away from the job; but even there, you mostly had to read between the lines to understand that, say, assistant district attorney Jack McCoy and his second-in-command Claire Kincaid were sleeping together. That season ended with an episode without a case to be solved, just the regulars exorcising various personal demons in the aftermath of witnessing a prisoner’s execution. (Most notably, Claire is struck and killed by a drunk driver while giving Lennie Briscoe a lift home from a bar.) Fan reaction to that season was mixed (the online TV forums I hung out on at the time were full of people dismissing it as a misguided attempt to copy the more popular NYPD Blue), and you could tell that the creative team didn’t feel comfortable doing it. They immediately went back into buttoned-down, “just the facts, ma’am” mode. You would learn non-work details about the leads, but usually just in passing, or at most to explain why they might be taking a particular case more seriously than usual. The deeper personal information would have to wait for the spinoffs, Special Victims Unit in particular.

Where the mothership had to very gradually immerse itself in the idea of doing more than alluding to non-work stories, SVU jumped in with both feet. Its pilot makes a conscious choice to introduce not just its heroes, but their families. With Stabler, it’s a relatively innocuous stop home so he can fix the kitchen sink, so we can see he has a happy marriage and kids. Benson, on the other hand, has dinner with her mother Serena (Elizabeth Ashley), and their conversation explains that Olivia’s biological father is the man who raped Serena. This makes every sexual assault case personal on some level for her, a fact clear to viewers even in episodes that didn’t explicitly talk about her past. In later seasons, Benson is herself assaulted, and eventually adopts a son who, like her, was the product of rape. Her job and her life are inextricably linked, and the audience knows it.

Stabler, meanwhile, suffered many physical and emotional wounds during his tenure on the show, including the temporary dissolution of that happy marriage, and big problems with his kids as they grew up. We know so much more about both of them than we did about Mike Logan or Abbie Carmichael or anyone from the original show, or even Bobby Goren from Criminal Intent. The audience not only didn’t reject SVU for getting more personal, they embraced it, keeping it on the air past the age at which NBC canceled the mothership.

Revealing more about the characters doesn’t just make the audience more loyal, but the actors. Some Law & Order cast members were fired over the years to liven things up, but others simply quit because they didn’t find enough depth in their part to keep doing it season after season. If Hargitay had grown similarly tired of playing Benson when, say, SVU was old enough to be bat mitzvah’ed, the show likely would have ended right then and there. She simply is SVU at this stage, and vice versa. And while it can survive her occasional maternity leave, it needs her over the long haul. Similarly, even after so many years away, Stabler remains a meaty enough role to provide reasons beyond a presumably hefty salary for Meloni to return after so many years of other kinds of parts (many of them opportunities to show off his prodigious comic talent).

NBC hasn’t provided screeners of either half of the crossover, nor of a “regular” episode of Organized Crime. So I don’t know what Stabler is like a decade later, or even whether the new show is any good. But it’s safe to assume that Meloni will get to bust out his trademark glower early and often, and that we’ll get more than vague hints about all the things that have been happening in Stabler’s life since he last worked with Benson.

As the narrator says at the start of each episode, “These are their stories.” SVU just puts the emphasis on their.