Mary Wilson on Style And Substance

Mary Wilson, the Supremes founding member who died last week at 76, may have been born in Greenville, Mississippi, but it was Detroit, where her family relocated when Wilson was three, that would propel her to icon status. The original girl group, which featured Wilson, Diana Ross, and Florence Ballard, formed in 1955 and would prove to be one of Motown Records’ biggest exports. With their boundary-breaking mix of style and talent, the trio helped pave the way for Black R&B musicians both at home and abroad.

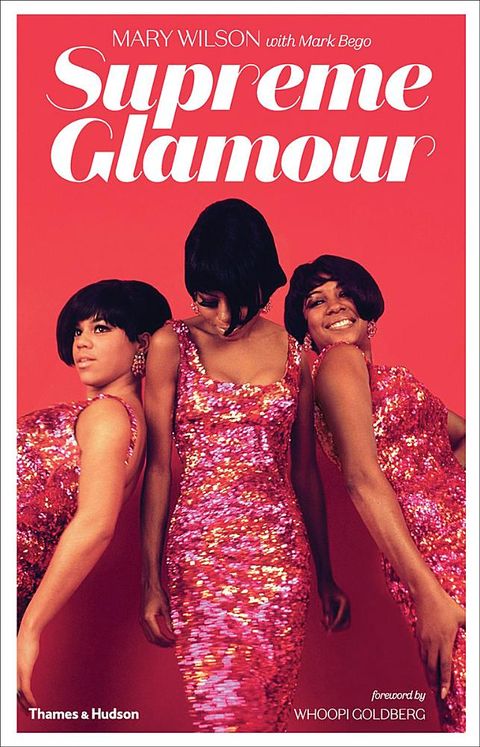

In 2019, I caught up with Wilson while she was in residence at New York’s Carlyle Hotel, performing nightly shows at Café Carlyle. It was the eve of the publication of her book, Supreme Glamour, a passion project of Wilson’s: She worked for years to track down the group’s lost costumes and establish an archive, the Mary Wilson Collection. Glamorous as ever and every bit as engaging as you’d expect, Wilson discussed everything from the early days of her career to experiences with racism in the Deep South and run-ins with royalty.

I loved reading about the early days of The Supremes and how you sewed your own clothes using Butterick patterns. Did that knowledge of sewing help you appreciate the elaborate costumes that would come later, and ultimately lead you on your quest to preserve them?

No, I don’t think it was that, I think it was our own parents. There were so many misconceptions about Black people in America at the time, that we were somehow uncouth or unsophisticated, but that’s nonsense. Our parents and aunts and uncles dressed beautifully: the hats, the suits, they were sharp. Black people knew how to dress and we really got that from our community. I can remember being in church on Sunday as a little girl and admiring the parade of these big, beautiful hats. And of course, Diana and I had Home Economics in school, so that’s where we learned to sew.

When the group started having costumes custom made, was it a collaborative process? Did you have any design input?

We didn’t but the beautiful part of that time frame was when we started doing TV. It was the height of variety shows like The Sonny & Cher Show, Ed Sullivan, and they had their own designers. We’d bought some nice gowns, I think off the rack at Saks, but when one of them showed us a sketch we were blown away. We were all wondering who was going to pay for all this intricate beading but it turned out to not be all that expensive, so we starting calling up the designers directly. Nowadays if you want a gown like that it’ll cost you $10,000-$20,000. We probably paid around $500 per gown.

You seem to be the self-appointed archivist of the group. What motivated you to try to preserve these garments?

Well, you put it nicely because my daughter says I’m a hoarder. But you can’t just toss musical history. So whenever a girl would leave, and Florence left first, she’d have to leave all the clothes for the next girl because the group was continuing on. Then Diana left so I got all of hers and so on until there I was, the keeper of the gowns.

But you didn’t quite have all of them. I heard one turned up in France recently?

It was the most incredible thing. We stored a lot of the gowns in Detroit at Motown when Motown closed and moved [and] some of the gowns went missing so now I have to buy them back. I’ve gotten calls from fans that have found them on eBay, and recently a woman in France found one at a yard sale. Now how did that get there? Others have turned up at museums as far away as Singapore.

Your struggle to get ahold of the gowns wasn’t your only struggle with Motown. You talk in the book about difficulties with contract negotiations and what ultimately led to your activism.

I’ve been involved in so many lawsuits I should have married a lawyer; it would’ve saved me a lot of money. The first was me trying to get the rights to the Supremes name because until Florence left, we all thought it belonged to us. Of course, the small print states that Motown owns the name. But all these groups were popping up and using the name, and not just our name. The Drifters, the Coasters, and several others. It’s basically identity theft, so we lobbied on Capitol Hill to get the Truth in Music legislation passed in 32 states. The next one, which I’m really proud of, is the Music Modernization Act. This particular bill protects people who recorded music before 1972 because if that music has since been streamed, you’ve not gotten paid. This will change that. President Trump actually signed it the day that Kanye West was at the White House, which is probably why the news got buried.

Technology has certainly changed the business. What are your thoughts on social media?

Look, I’ve got enough going on that I could have a reality show, but that’s not me. There’s a photo in the book though, taken around 1956. We’d just landed in England and we’ve got our little Beatles suits on and are being swarmed by photographers before the word “paparazzi” was part of everyday language. We had a lot of firsts and sometimes I hate to brag, but people don’t realize that back then a lot of these things were nascent and we were some of the ones that got it started.

Did you ever keep a journal?

I kept a diary from the time I was 17 years old and in the 11th grade, my teacher Mr. Boone said, “Ms. Wilson, I know you’re singing in this little group called the Primettes [a precursor to the Supremes], but if you don’t pass my class, you won’t graduate and you won’t be able to go out and sing with that group.” That scared me. Berry Gordy also said we had to finish school, but the truth is our parents would have killed us if we hadn’t. So I wrote a term paper for Mr. Boone about my first 17 years, which were quite interesting. I wasn’t raised by my mother but by family members who I thought were my mom and my dad, and then they told me the truth when I was about 10. It totally freaked me out and so I wrote about that. Mr. Boone was this very proper sort of Black guy and he said, “Ms. Wilson, this is fabulous! You should definitely think about becoming a writer.” All I could think about was going down to Motown and recording.

I’d go down there every day and would meet people like Marvin Gaye, Sam Cooke, Stevie Wonder, so I started keeping a little journal up until about 10 years ago, when I was just too busy. I never really went back and read them but because I had put pen to paper, I had the recall, down to the color of the walls. And I tell everyone to do the same because you can pass it down to your child. I wish I’d had that kind of insight into my own mother as a young woman, but I’ll never know.

At several points in the book, you recount stories that made you feel as though your career path was almost preordained, like your etiquette coach at Motown who said that one day you’d be singing for kings and queens.

Mrs. Powell said some of the most wonderful things to us, such as “you are diamonds in the rough and we are just here to polish you.” The impact of saying that to a young person is just immeasurable. She was such an elegant woman and I always felt good when we were able to honor her. Motown artists always stood out, wherever we went.

So, when we were in London, her prediction came true, and after the show we met Princess Margaret, who had the nerve to ask if our hairdos were wigs. It wasn’t the question but how openly she asked it. I couldn’t believe how uncouth she was and thought how much she reminded me of some of the people I’d grown up with in the projects in Detroit. I learned a lot from that that helped me throughout my life, and that’s that a title doesn’t make anyone better than you. And then we became friends.

As the longest-running member of the Supremes, what kept you going?

Well, I think I’m one of the fortunate ones, and I think Diana would say this too, because we started very young and we all had the same ideas about music and style and were just really in sync. I’ve always said that when I met Florence and Diana, I felt that I’d met the other parts of myself. I totally enjoyed singing and never wanted to do anything else after that. I had never thought of singing as a career; I just thought everybody woke up singing. I enjoy being up on that stage and making people smile. I’ve found what I love to do and I don’t want to do anything else, though this has led me to do other things.

Motown is synonymous with Detroit but you were actually born in Greenville, Mississippi. What was that like?

I was born in 1944 in Greenville, Mississippi. My parents had a home there, right off the levee, and we left when I was about three in that Great Migration from the South because of jobs. Many people left for Detroit as well as cities like St. Louis and Chicago. Every summer we’d either drive or take the long train ride back to Mississippi to visit family, so of course, I was aware of the racism there. Around the time I graduated from school, in 1961, my dad died and we went back for the funeral. I was downtown shopping for gloves for him to wear, as you did in those days, and one of my cousins said to me, “now Mary, you be good, okay? You don’t know these people around here.” Meanwhile, I’m from the north and I’m turning my nose up at some of the things in this shop, saying things like, “I don’t know about those socks; they look cheap.” So my cousins are whispering, “Mary, please be quiet, they’re watching” and I’m like, “Who’s watching? So what? I’m trying to get the best for my father.” So when I got up to the counter the old man says, “Yeah, I can see she’s not from around here.” And my cousin said to me, “Mary, I’ve still gotta live here, so you’d better leave that ‘up north’ stuff up north.” I definitely gained an understanding of the “southern way” though I experienced nothing like that in Detroit. It was quite eye-opening.

My mother is from Selma, Alabama and mentioned that all through high school, her older brother had photos of The Supremes plastered on his bedroom walls. I found this such an interesting image given everything that was going on there at the time.

Because the music really did transcend any racial situations. Even the radio stations of the time found a way to segregate the music, but people still found a way to listen. Bill Wyman of the Rolling Stones would talk about how sailors would come here and buy the records and carry them back to England to be played on pirate radio because the BBC would only allow certain traditional music on land. So the Beatles, the Stones, the Dave Clark Five, they were totally into the music before radio was. It was a great export for America

The Mississippi Delta has such a rich musical history. Was that at all an influence on you?

Absolutely, because of our parents, that’s all they listened to. My father had a huge collection of blues albums but at the time it wasn’t really my thing. I was speaking to Bill Wyman about how the Stones probably knew more of the blues than we did because my generation wasn’t as interested—because it was our parents’ music. But I do think it penetrated my soul and I think the same thing is happening now with music from the 1960s: Young people absorbed it in their parents’ homes and now they’re singing it.

Many people aren’t aware of what a fashion plate Whoopi Goldberg is. Is this why she was chosen to write the forward?

It actually had nothing to do with fashion but more about Whoopi as a person, and of course it didn’t hurt that she admitted to having wanted to be a Supreme as a kid! At the time, there were not a lot of Black people on television. Hattie McDaniel may have won an Oscar but only one side of the Black experience was being portrayed. Whoopi said when she first saw us on television it was like “wow, here are three glamorous, Black females.” There were well-known Black film actresses, but television changed the scope of what people allowed in their homes. So when I heard Whoopi recount that story I knew she was the first person I had to call because we felt how impactful it was, too. And there were three of us. And I know that it didn’t only inspire Black women. We broke a glass ceiling for all women. The saying for so long has been that “behind every great man, there’s a great woman.” And that’s true. But now she can just as easily be alongside him or even in front.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io