Malcolm & Marie Isn’t a Story About Love. It’s a Story About Power.

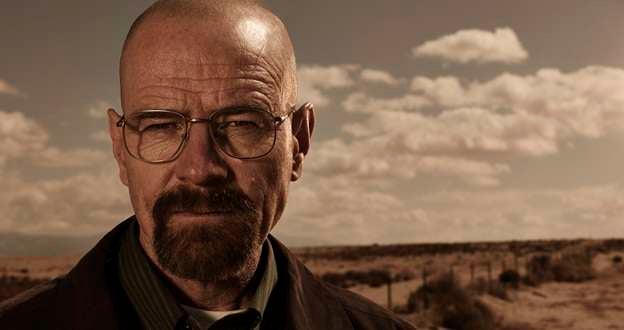

“This is not a love story. This is the story of love.” The bare-bones black-and-white trailer for Malcolm & Marie prepares its audience for a dish-smashing, insult-hurling, love-making saga familiar to any couple with unresolved issues stuck together in quarantine. And the movie certainly delivers on that front. But it’s the specificities of this couple—a Black director (John David Washington) basking in recent success and his gorgeous, professionally stunted younger girlfriend (Zendaya)—that sets this movie apart from, say, Revolutionary Road. This is a story about power and powerlessness.

Malcolm & Marie opens with Malcolm practically skipping into the beautiful rental home provided by his producers in a dapper suit, chest puffed out and raving about the success of his film’s premiere that night. James Brown’s lively “Down & Out in New York City” plays as Marie, reticent in a shiny cutout gown baring her flat stomach, aggressively fixes his supper from an unceremonious box of Kraft macaroni and cheese. It’s clear she’s upset about something, but his dinner cannot go unmade. Besides, he’s not done boasting.

Writer-director Sam Levinson drops us inside a moment between two people we rarely see behind closed doors—the successful older man and the so-called “love” of his life—and forces them to reckon with how they’ve used, or misused, each other. What may be considered a minor offense to some is the impetus of an argument that lasts the entire film: Malcolm forgot to thank Marie in his speech during the event. While it could be an innocuous omission, it suggests a general lack of appreciation for the role she’s played in his life. That’s especially true when it comes to the trophy girlfriend dynamic, where power and appearances are of the utmost importance, and that’s exactly where Malcolm & Marie sits.

It’s not pretty. It gets loud. Expletives explode out of their mouths. Feelings are hurt between bouts of affection, as songs like Duke Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood” play. The camera painstakingly tracks each exasperated eye-roll, scream, caress, and angry pace along the plush carpet.

“I didn’t realize what I was to you, a fucking movie,” Marie tells Malcolm in a moment that crystallizes her disappointment. His film centers a struggling female artist and recovering addict—just like Marie—and she knows he couldn’t have made it without her. In fact, she auditioned for the role and he rejected her; she reminds him by reenacting a scene with flawless precision, scraping a knife across the floor as she recites his lines about refusing to get well and sleeping with his friends. The scope of Zendaya’s performance is evident as Marie pivots, in an instant, from this jarring portrayal to her real, wounded self. Hugging her feet on the floor, she says in a small voice, “You fought to get the movie made. Why didn’t you fight for me?”

It’s simple to call Marie desperate for her partner’s validation—and she surely is, as anyone in a relationship in which they’re patronized and devalued might be—but Malcolm also needs her. She feeds his ego, calling his work brilliant (later, when they return to sparring, she tells him he’s just mediocre), and grounds him when he goes off about elitists—though he in fact is one. He’s so absorbed with himself and how other people feel about him and his work that he explodes when one journalist writes about his film precisely through the lens he doesn’t want it to be seen: political. “Cinema doesn’t need to have a message. It needs to have heart!” he shouts. Malcolm is so enraged, he needs Marie to find his phone so he can finish reading the review.

In an effort to assert some of her own power in their relationship, Marie offers a worthy critique of Malcolm’s film and explains how his heroine is oversexualized. But Malcolm dismisses her claim because he thinks she sexualizes herself, using her see-through tank and lack of bra as evidence. But really, it’s Malcolm who objectifies her—as Levinson’s proxy and through the director’s camerawork. Should it matter what Marie’s wearing in this scene in order to take her, or even Zendaya, seriously? Perhaps that’s what Levinson wants us to wrestle with.

Because Malcolm sees Marie as nothing more than a pretty ornament he’s saved from herself. While he claims he loves her, he also tells her, “When I met you, you were a fucking pilled out-disaster! You were 20 years old!” So, why did he want to be with her? Because rescuing her made him feel like a bigger, better man—and it still does. His own insecurities and hero complex wouldn’t have it any other way. “You’re not the first broken girl I’ve known, fucked, or dated.”

Malcolm & Marie isn’t so much a story of love as it is a prototype of a stubbornly imbalanced and toxic relationship. It’s just that now, both parties know it. As much a sexual object to Malcolm as Levinson’s lens makes her to the audience, Marie would be reduced to a trinket if it weren’t for Zendaya’s thoughtful interpretation of the script.

And it’s actually Malcolm & Marie’s message, not its heart, that makes it such a searing watch. With its terrific performances, resonating dialogue, and elegant single-setting production, the film compels us to see beyond a couple clamoring across the house and acknowledge that a perpetually underestimated woman has found her voice. When Malcolm finally utters the words “thank you” by the end of the film, one song from its jazzy soundtrack lingers: Dionne Warwick’s “Get Rid of Him.”

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io