Salamishah Tillet’s Love Letter To The Color Purple and the Black Women Who Came Before Us

One of my fondest childhood memories is sitting in my grandmother’s living room, watching The Color Purple. Details like the year and my exact age are hazy, but what’s crystal clear is that, despite having watched the film a hundred times before, witnessing Celie’s journey with my Granny, mama, and Aunt Mae felt like the first time. As three generations of Armstead women laughed, cried, and loudly sang, “Maybe God Is Tryin’ To Tell You Somethin’,” we shared an unbreakable bond: a spiritual connection that no one else could replicate or take away.

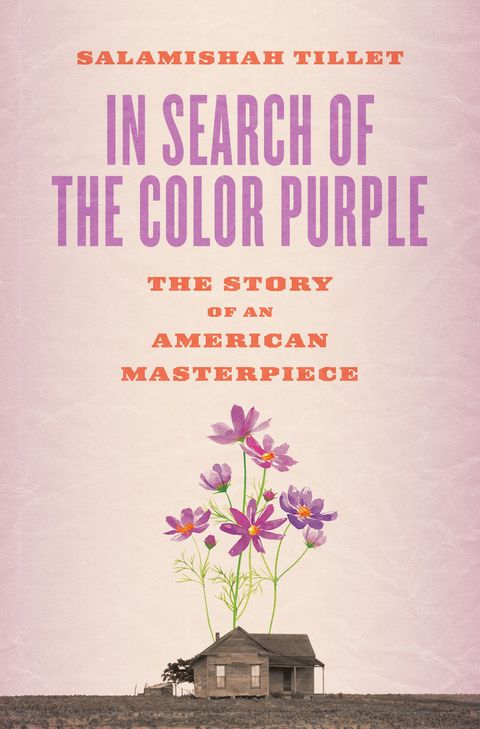

These are the exact sentiments—and much more—that author and New York Times contributing critic at large Salamishah Tillet captures in her captivating new book In Search Of The Color Purple: The Story Of An American Masterpiece. Through archival footage, interviews, and her own analysis, the Rutgers professor proves Alice Walker’s 1982 book is more than a Pulitzer-winning novel, 1985 Steven Spielberg film, or Tony-winning Broadway play. As Tillet stresses, this story of sisterhood, sexual violence, healing, and resilience is a rite of passage for many Black women, a necessary thread that connects us to those who have come before, especially our ancestors.

Tillet also pays homage to the beloved characters by dividing her book into three sections—Celie, Shug and Sofia—that take us on a journey of uncovering and rediscovering how this beautiful tale was conceived, birthed, and has thrived for nearly four decades.

Of all the Alice Walker books to love on, why The Color Purple?

First, this book is the one that she is clearly the most famous for. That and The Color Purple has had so many lives beyond what Alice believed it could have. I think it’s also the book that haunted her the most. For me, I was introduced to the book at such a pivotal age, along with Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and The Autobiography of Malcolm X, but I couldn’t have revisited those two books with the same consistency or traced who I am as a Black woman now to those other texts. There is just something about The Color Purple that makes it timeless, special, and unique. To this day, people are still obsessed with this story and have testimonies on how it helped them shape their lives and played a role in their healing. Just when it feels so old, someone will tell you they just watched the film last week. It resonates so much with Black women.

I love how you infused your personal connection to the book with all the ways the story has been imagined, anecdotes from conversations you had with Walker, and her personal journey that led her to write The Color Purple. Why this type of deep dive?

Honestly, we just don’t do this with Black books. We see this done with Woolf and Whitman and examine how they wrestle with themselves and wrestle with the work. I wanted to do that for Alice to emphasize that this work matters. For me, it was so important to take that type of critical eye and compassion to a Black woman’s work and to treat it with care.

The book is peppered with refreshing moments of vulnerability, with Walker confiding in you these stories about her family, her writing process, and more. How did you gain her trust?

To be honest, I was overly intimidated by her. I have so much respect for her, and this book has had such an impact, so to do this type of work, you have to meet that person’s intellectual curiosity. She’s been asked thousands of questions for nearly 40 years about this book, but thankfully, Gloria Steinem [who writes the forward for the book], Beverly Guy-Sheftall and Valerie Boyd, who I am close to, are friends of Alice’s too. In the best of feminist tradition, they represented for me, prepared us for this meeting, and warmed her up to me. They made sure she knew I wasn’t some person who wanted to come into her house and do weird stuff. [Laughs] I also brought my sister Scheherazade with me, and they hit it off and their immediate connection helped. It made sense because the book is about sisterhood, and the more we talked about our experiences together, she grew to support this project.

Despite being an expert on The Color Purple, did you learn anything new during your writing and research process?

Definitely. I didn’t know how intimate the characters were in Alice’s family. We usually associate Albert with her grandfather, but it’s only through reading interviews or work from her over years, or talking to her, that we learn the character Sofia was based on her mother, or that Shug was a real person who shared a husband with her grandmother, who Celie was based on. So, when all the attacks about the book came, they weren’t just attacking characters on a page—these were real people and that pain of those attacks was very real for Alice.

I also didn’t know that Black men like Quincy Jones [one of the film’s producers] and Danny Glover [who played Mister], were so committed to telling this story onscreen, committed to sharing these stories and loving these characters—and they sacrificed a lot to do so. Glover talked about how much he identified with this story, and how he saw parts of Celie in his grandmother. In all the backlash about how the film portrayed Black men [accusing them on leaning in on racial stereotypes], we don’t always remember this type of compassion. There are always going to be people who are sexist, but there are also Black men who see the power and value in Black women’s art and their voices.

Speaking of voice, there’s a passage in the book when Walker, who is in tears, shares her pain in seeing her grandmother’s voice silenced. As a Black woman, I often wonder how silenced my Granny was and the sacrifices my mother made for me to have a voice now. There’s a Celie in so many of our families, paving the way for us.

I think about this often. Our ability to have these conversations and debates and fight these battles now are because of the women who came before us. When we look to the revered Black feminist figures such as Alice Walker, June Jordan, Toni Morrison, and Audre Lorde, and how we are different than them and the freedoms we have, they had to pay a huge cost trying to be free women and to be writers and thinkers. What makes Celie so powerful today is that she exists inside and outside of time, and that is a gift Alice gives us, a gift given to her by her ancestors.

So many of the same themes of sexual and domestic violence in the Black community that Walker tackles in The Color Purple and her other books continue to ring true today. In an era where Black Lives Matter and the #MeToo Movement collides, why is it so important to center and prioritize Black survivors?

This is one thing Alice is trying to teach us: Keep centering Black women and girls. In The Third Life of Grange Copeland, she is writing a book about domestic violence at the height of the civil rights movement. For her, and to me, the key to our freedom is existing in a world where we are free of silence, free of violence in our homes, and at the hands of the police—free from violence that takes place in public, or with our partners. For too long, we’ve imagined that the quest for racial equality doesn’t include Black women being fully formed and free of violence. It’s not only state violence that brutalizes us, and The Color Purple reminds us that half of us being free isn’t enough. We have to eradicate all forms of violence.

Finally, Walker speaks in-depth about the ways that Celie wasn’t believed or protected. Looking at where we are now in this country, especially the recent takeover of the Capitol building by mostly white domestic terrorists, why is it dangerous to not listen to Black women?

The cost we pay for not listening to Black women is Donald Trump. While in 2020, there has been this increasing recognition of us as political laborers and as activists and artists [who make change], it’s not enough, given how much we are actually right. And it’s not enough given how much we sacrifice for this nation and our community. And at some point, we have to acknowledge and center those who are not just fighting for themselves or to be their full democratic selves, but for everyone around them. Even if and when we benefit from it, the instinct isn’t self-preservation. It’s about the collective good. You see in The Color Purple how much everyone relies on Celie’s journey to healing because it helps those around her heal—even Albert, the one who hurt her the most. This is why Black women need to have both the space to be heard and to heal.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io