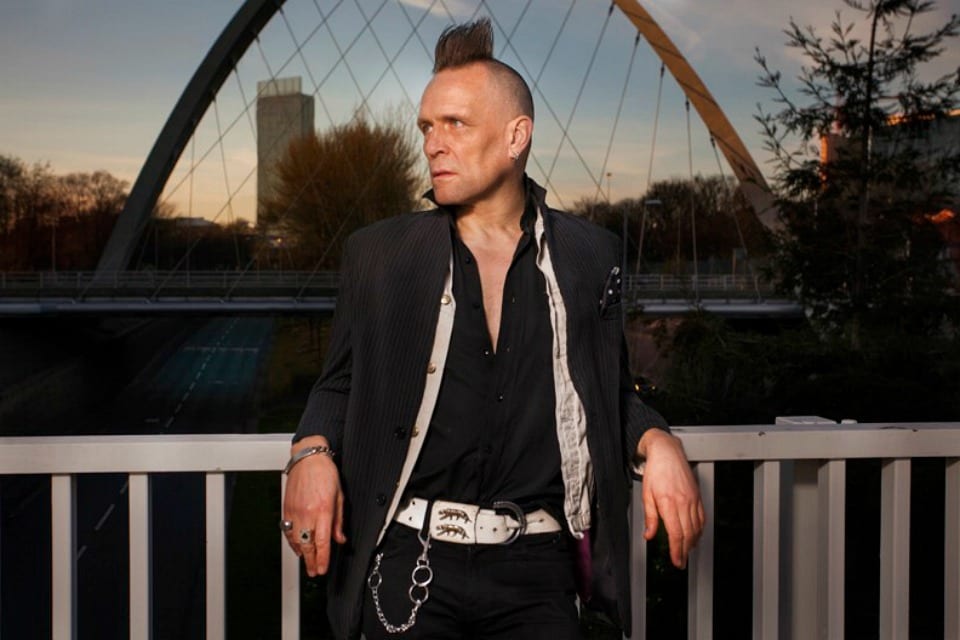

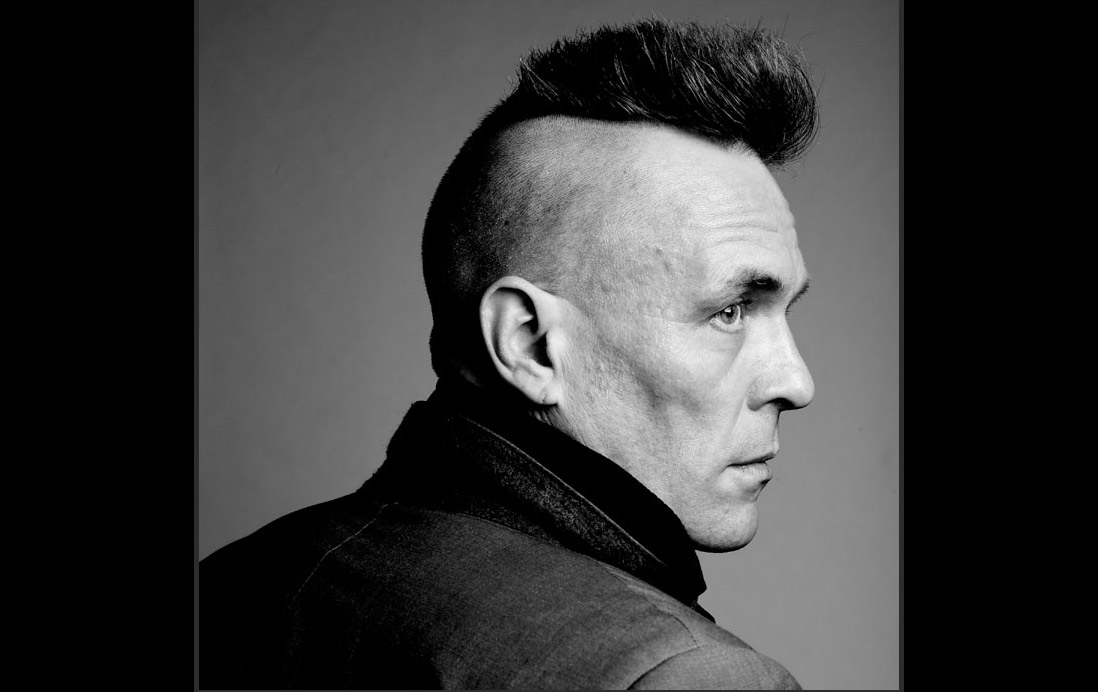

An Interview With John Robb by Edmund Barker

John Robb is fixture of Manchester’s idiosyncratic culture, being a part of the band The Membranes amidst the seventies Northern English punk scene that birthed Joy Division. By the late eighties he had gone into rock journalism and was the first reporter to interview nascent indie bands called My Bloody Valentine and Nirvana. I had a long chat with him about his magazine Louder Than War and misadventures featuring near-death experiences on more than one occasion.

EB: Now, I’m real excited to talk to you.

JR: Whereabouts are you?

EB: Seattle, Washington actually.

JR: Been there about three years ago.

EB: Rare sunny day here, I was gonna say.

JR: Yeah, you have the same weather there that we have. It’s just great! That’s why I like it there, I feel at home.

EB: I was just talking to someone else from the UK about how similar the weather is.

JR: And how about the virus over there, is it still crazy?

EB: Yeah, it’s a madhouse…[sigh]…we’re just sorta haning on until some stimulus hopefully early next year, but…I can’t really compare it to how good or bad the management of this thing has been over there.

JR: We’re like a slightly less worse version of you! Same kind of problems with leadership [chuckles]. Yours sort of took it further though.

EB: Yeah, we’re two peas in a pod right now, unfortunately, with our leaders.

JR: And we get the worst ends of it over here.

EB: The “special relationship,” as it’s called.

JR: A kinda made-up one that doesn’t actually exist. You find that out when you’re a musician trying to get visas to tour America and it’s twelve-thousand quid! And thirty-thousand quid for an American coming to the UK. That’s the special relationship for ya!

EB: Well, I didn’t know that. Now, it’s funny you should make me bring up the topic of Seattle, since I read that when you were in music journalism in the eighties, you were one of the first people to interview Nirvana?

JR: I was the first one, apparently! I had no idea. It was only when a book came out of all their interviews and I was the first one in there and I said to the guy, “surely there must be someone before me?” And that was the first one. They were sort of looked on as being Sub Pop’s first mistake. Because Sub Pop had a very basic model, and Nirvana was just starting out…it took a bit of time [for them to get big].

EB: Did you think at the time that they were gonna go on to huge success, or were they just one of many indie bands you encountered?

JR: They were just one of many bands I thought was pretty brilliant, but no one else was ever gonna like! I generally wrote about bands that only I really liked, and saw some of them get popular, but Nirvana got the most popular.

EB: Well I’m sure you were glad to be proven completely wrong about their appeal.

JR: [laughs] I’m always glad to see bands make it, because I know how difficult it is to get up the slippery slope.

EB: Yeah, I’ve always been kinda interested in Nirvana’s very early underground days. I went to Evergreen State College a few hours from Seattle, and that was one of their first gigs ever, at the college radio station, I think in 1987.

JR: College radio was key to America then, really important.

EB: So many of my favorite groups like XTC and even The Cure get lumped under that college rock label…I dunno how much it was used in England. I guess for Americans it was a catch-all for intellectual, artsy, different bands like R.E.M. or Pixies.

JR: Yeah, they all genuinely were underground. I saw XTC play a couple of times, there were hardly any people at the gigs. I saw The Cure in the early days…it felt as big as it was ever gonna get with The Cure playing to three-hundred people, but last time I saw The Cure they were headlining Glastonbury to about a hundred and fifty thousand people. The cool thing was, they were better now than they ever had been.

EB: They are on my bucket list of bands to see for sure, though this year has put a dent in my plans.

JR: I think that about halfway through next year, things will start to happen again. There might be some festivals, outdoor first…gonna work out a system to have it without the whole audience getting ill. In a year from now it won’t be like the old days, you’ll probably have to take a test to get in a club or something, and there will be people complaining about that…it’s gonna be bumpy, but in several months it’ll get better. That’s what I think, anyway!

EB: I’m holding out hope for next fall, yeah. I’m pissed that I missed a New Order/Pet Shop Boys double bill that would’ve been this a few hours away from me this past September.

JR: That’s almost like the same gig for three hours! [laughs]

EB: Would’ve been in this great amphitheater called the Gorge, kinda looks like the Grand Canyon. Just the venue is cool too. Anyways, one question I have is: when I heard you’re part of the Manchester indie and punk scenes, my mind went to these bands I love like The Farm, Happy Mondays, and of course New Order. I wanted to ask you, what do you think caused this creative explosion in eighties Manchester aside from all the drugs?

JR: Well, for a start, I was in Blackpool initially, which is fifty miles to the north of Manchester, but it has a lot of links to Manchester. So the music scenes were connected—there was a band in Blackpool called Section 25 who were on Factory Records, and it was Ian Curtis’ favorite band, so he would come every weekend to Blackpool—when he wasn’t touring—just working with them and their songs. And their debut album is brilliant, I dunno if you’ve heard it, but you should go look it up. If you’re a Joy Division and New Order fan, you’d really like them. They’re very parallel, musically. So we were very connected to that Manchester scene. The fact is, the reason why Manchester has such a big music scene is because, very early on, Buzzcocks had the Sex Pistols on twice in Manchester. It was the first place outside of London where the Pistols really made an impact. And Buzzcocks, I think, are a very key band. They lent Joy Division money to record their debut album, and also put out the first independent single of the punk rock generation. They encouraged local bands, and they had their own label, which encouraged Factory to start their label. And the other factor was Tony Wilson, who was famous in the north already as a newsreader, he was a very dynamic force, encouraging people as well. Manchester is a very big city, so things would at some point explode…we had an infrastructure and people who wanted to make things happen, and they did. And I think it was punk because a lot of people saw the opportunity to do something artful, on their own terms, and Manchester just took that opportunity.

EB: Do you think there was a sort of an escapist element to the music of that time, with Manchester being sort of a depressed city?

JR: Yeah, at that time—it’s very different now—it was a post-industrial city in decline. I remember going there the first time and most of the city center would be boarded up, but if you come here now then the whole city center is expensive forty-story tower blocks. It looks like Manhattan now, it’s a completely different place from what it was forty years ago. But you could argue that the new Manchester was inspired by the music scene, because the whole center of the city looks like the Hacienda (nightclub) now—which is ironic because the Hacienda doesn’t exist anymore. But the spirit of it has kinda gone through the whole city. So at the time, yeah, the music was an escapist thing. But there were other things going on. I mean, Manchester even then was a media city, a lot of TV got made in Manchester. So it wasn’t completely derelict and cut off, there were things happening here, and there were spaces where things could happen, which is important as well.

EB: Glad you brought that up, because once I can go to the UK again, I’m making a beeline for Manchester to see places like the former site of the Hacienda. I had already known that the Hacienda is a fancy apartment complex now, so can you elaborate on some of those big changes to the city in the last thirty years?

JR: I think maybe ninety percent of the buildings are different. I mean, Manchester now, if you’re an eighteen-year-old growing up in Manchester now, your vision of Manchester is utterly different. It’d be like big blocks in the center and expensive flats. It’s got the most flats being built in Europe right now, and the most cranes on the horizon…and I think a lot of that came out of that empowerment from the music scene, you know, the idea of giving the city a new identity. I would speak to Tony Wilson years ago, and it was his dream that Manchester would become a city where people lived in the center, like American cities. In the late seventies hardly anybody lived in the center of Manchester, and now thousands live there. On every level, it’s completely different. But music was very important in that, that sense of empowerment, that sense of daring to do it. So the Hacienda is gone, it’s just flats built on the site, but in the same shape as the Hacienda, so it looks like the same building when it’s not. But there’s still a few things left, like the Joy Division bridge—you know, the famous photo, the Kevin Cummings photo of them standing on the bridge. That’s still there, I live right next to that. And the Salford Lads Club is still there, where The Smiths did their photograph standing out in front of the doorway. If you come to Manchester I’ll show you the sights!

EB: That’s a plan. Someday.

JR: Yeah, next year!

EB: Now I was thinking the whole economic development and transformation of Manchester was something that happened sort of in spite of its music scene and counter culture, but you’re saying that it was more connected to it.

JR: Yeah, I think so. It’s inspired by it, it’s empowered by it, it’s connected to it. It wasn’t a broken city, it was one that was going forward—in the eighties, culturally, it was ahead of London, it was ahead of the rest of the country. And it’s continued with that sort of attitude and spirit, and it’s entwined with the music and culture, but also the tarred twine and the bricks and mortar of the city itself. So we went from an industrial city to a post-industrial city to a post-punk city, which is kinda what it is.

EB: Now Madchester, or rather “baggy,” is one of my favorite genres. It strikes me that some of the big bands like Stone Roses and Happy Mondays had kind of a quick flaming out before the halfway point of the nineties…is there a real reason for that other than just some of the chaos of the drug lifestyle?

JR: I think there’s a few factors. Yeah, that’s probably one factor, people do get burned out. But I think that willful determination and willful eccentricity, of completely doing things on your own terms—which is very Manchester—is the making of many bands but also the breaking of them. So everything that would’ve made someone like Morrissey great when he was twenty-one is what makes him not so great when he’s sixty! There’s something here with all the bands where the singer is like one thing, and the guitar player is like another. [laughs] You see how it plays out in all these different groups. The singer seems to go quite mad, and the guitar player seems to hold the ideal of the group. So I think there’s definitely a self-destructive nature chemically, but also spirit-wise, attitude-wise, which feeds into all the battles. There’s few bands anyway that keep their line-up through their whole history, but in Manchester, if there’s an argument, nobody steps down! So when Hooky and Barney [of New Order] fall out, nobody’s ever gonna make the phone call to say, “I’m sorry about that!” That doesn’t happen, so they’ll go their graves hating each other. [laughs]

EB: So that’s true of a lot of Mancunian bands, not seeing eye-to-eye?

JR: No…there’s a time where it works, and that’s about five years. I think a lot of the bands, they tend to have more than one dominant person, whereas London bands are more of a team…you know, they have one driving force and the rest work as a team behind them. With Manchester, there’s always two, maybe three dominant forces in each group. You see that with Morrissey and [Johnny] Marr, you see it with John Squire and Ian Brown, Hooky and Barney…see, the problem they had is that their dominant force died, so the next two alpha males of the band came up. You know, it’s actually amazing they kept it together as long as they did, you have to look at it the other way round.

EB: On the topic of 24 Hour Party People, that movie made me fascinated by Tony Wilson and the idea of going from a local newsman to a punk label boss, that career transformation is interesting itself.

JR: Well, it actually makes a bit more sense if you dig through it, because before punk he was like the young newsreader on local TV, but he was like the hippie with long hair and an open shit…all the grannies use to love him, he was quite charming. So even though he was not a conventional local newsreader, everybody liked him, he had the charisma. And it was quite flashy for a Northern local news network, at the time, to have a pretty cool person reading out the news instead of some stuffy one from fifty years ago. And then because he was into the arts already—he was a massive Bruce Springsteen and Joni Mitchell fan, and music of that generation—they gave him his own arts program, and it was the first program in the whole world the Sex Pistols played on it. So, people always think the Bill Grundy interview where the Sex Pistols swore on the TV was the first time they were on television, but they were actually on Tony Wilson’s So It Goes six weeks before. And in punk times, six weeks could be centuries! We had all this stuff when we were growing up, the rest of the country didn’t get to see it but we saw all these bands on TV. You’d see the Sex Pistols, Television…all these bands coming in from America, he’s put them on. In those days, pre-internet, it was amazing to see stuff like that. You couldn’t see these people in color, you’d just see smudgy, black-and-white pictures in the music press, but we had it on our local TV! So I think that might’ve actually been another factor in why the Northwest had such an advanced music scene. They were about a year ahead of the rest of the country, because we could actually see this stuff.

EB: That makes sense, that Wilson was already sorta the hipster type before he started Factory Records.

JR: Yeah, completely. And he was really well-known in the Northwest. Initially some people thought it was a bit weird, but if you actually know his story, it makes complete sense. A very dominant personality, he could go to the bosses of the local TV station and say “give me an arts program!” and they’d give him an arts program. He was full of enthusiasm and willpower. But when he saw that Manchester had its own great music scene, that’s when he realized he could create something very interesting. So I think what he did, in a lot of ways, took what the Buzzcocks started and made it into a thing. Just never forget Buzzcocks, that was so important to the whole story.

EB: They were before Joy Division even, right?

JR: Yeah, Joy Division supported them on their breakthrough tour. Buzzcocks were the first punk band outside of London, they took punk out of London and gave it to the rest of the world, in a sense. It was a very cool, London clothes shop scene, and Buzzcocks took it to the North of England. In cultural terms, what they did is amazing. And I think they’re one of the greatest punk bands this country has ever produced; melodically, Pete Shelley is amazing. I don’t think they get mentioned enough. Culturally, they were such a vital group.

EB: So you talk as if you knew Tony Wilson. Do you have any stories about him?

JR: Yeah, knew him really well. I would see him nearly every day, he would come back from the gym. He only lived about five minutes away from me, he lived in town rather than the edge of town and I bumped into him quite a lot. We’d generally have arguments about music, because everybody’s opinionated here, and nobody backs down. [chuckles] So you’d have these fantastic discussions and debates, about the minutiae of music and culture.

EB: That argumentative attitude I guess goes back to what you’re saying about bands who don’t get along.

JR: Certainly, it’s a good thing, but I think it can be destructive as well. But it’s certainly worth having, because otherwise you just end up being wishy-washy. The attitude of a lot of bands here was “I do what I do, like it or not. Id you don’t like it, I really don’t care.” And that was perfectly embraced by The Fall, who are sort of like the uber-Manchester band, attitude-wise.

EB: They were a post-punk band when that was just a catch-all to describe bands who didn’t entirely fit in punk.

JR: Yeah, that’s another thing. Even though Manchester embraced punk, it didn’t embrace it on London’s terms. So, people didn’t dress up here, they didn’t make music in a similar way. I mean, I love the London punk scene, but a lot of it was more old rock and roll like Chuck Berry. Clash and Pistols, they’re amazing bands, but they’re just rock and roll bands who played louder. In Manchester, it was more about being not rock and roll, so Joy Division, Buzzcocks, they’re all a different kind of music. I mean, even if Buzzcocks played with buzzsaw guitars, they’re as influenced by Kraftwerk as they are by rock and roll. They don’t have poppy guitar solos or twelve bars, that’s more of a London thing. It was different here, it was a determination to make a new musical carnality and language. Less flashy, deliberately dour, which is an art form in and of itself. Which is interesting because in Liverpool it’s quite different. Even though there’s connections because there was an interest in psychedelia as well, in Liverpool it was more dressed-up, a lot more flamboyant characters in Liverpool. And Manchester was about the dourness, and celebrating the dourness!

EB: As you can tell I’m sort of an amateur Madchester historian, anything involving acid house or the Hacienda in the late eighties and early nineties. I was wondering, do you have any recommendations for books and media about that time period aside from 24 Hour Party People?

JR: Well, you can get my book! [laughs]

EB: Ah, a little self-promotion! Okey-doke.

JR: Hey, you did ask! The North Will Rise Again, it’s called, and it’s an oral history from people who there…there’s a load of books, there’s a whole bookshelf of books about it. I like Peter Hook’s books, I think he’s a really good writer. He writes books about Joy Division and New Order and the Hacienda. So I’d recommend that.

EB: Alright, your books and Hooky’s. I’ll put ‘em on the Christmas list, still time.

JR: Yeah, just in time for Crimbo!

EB: Now, back to your music career—and I wanna ask you more about your journalism career in a moment—but when you were first starting out, making music, what were some acts that inspired you apart from the big ones mentioned like Pistols and Buzzcocks?

JR: It was that, and also music before…I used to like glam rock growing up, so it would be like the usual Bowie and T Rex, but also some of the other glam rock groups as well. Mott the Hoople, Slade, those groups. Not that I meant to sound like those bands, but they made you want to be in a band. Punk opened the door for you to go and do it, but you wanted to make your own version, you didn’t just wanna be a copy of somewhere else. It had to be as original as you could possibly make it, which gets pretty difficult when it’s just a few people in a room with guitars, bass, and drums. It’s not that many permutations in the end…but somehow we managed to find one! You had to make your own style musically with what you had, and also limited by your playing abilities as well. Nobody played properly, you just had to get on stage, make music, and learn as you went along. That’s quite important as well.

EB: Lot of overlap, I guess, between glam rock and punk—all about scaring old folks.

JR: Yeah, things were like that then, weren’t they? It was interesting, because there was definitely a generation gap that existed until probably the mid-eighties. And now you go to gigs and it’s like, parents, grandparents, and kids all go to see the same band. It’s kind of cool, but it’s not great motivation to make music to annoy your parents—you just wanna make music, don’t you?

EB: Another thing I gotta ask you about: I read that you and your band were asked to reunite specifically by the members of My Bloody Valentine in 2010. That’s a pretty incredible story!

JR: Well, when they started, they used to support us at gigs, and I did the first ever interview with them in the music press. We had a lot of connections, and my guitar player plays on their first record. It was just a payback, really—after all those years they did a festival, and they could pick all the bands to play the festival. They paid us really good money to play the festival, we had no intent to reform. And then when we played a lot of people came, and went, “oh, they actually remember us!” But then we didn’t just wanna go around playing old songs, so we made new records, which got really good reviews…and somehow, it just kind of escalated from there. And My Bloody Valentine played pretty much the same scene as us, they played a lot of the same venues in the same time. We just watched them get bigger and bigger. And they’re great, they’re a fantastic band, but they’re not the loudest band, which people always go on about—loudest band of all time. And I think, have these people ever heard Motorhead?

EB: I saw you interviewed the band Mogwai, and when I saw them in 2014 I really thought, “now this is loud, I’m gonna have ringing in my ears for a bit from this!”

JR: Well, they are loud, but they’re not the loudest group. Their trick is to have very quiet parts and very loud parts right next to them…I think they’re a fantastic band, Mogwai, in way they’re like cousins. We all know each other, of course. What they feel attitude-wise, or what they try to do in music, is similar but comes out in different ways. We definitely feel related to them.

EB: Back to My Bloody Valentine, they’re from the Dublin area, right?

JR: Initially. They grew up in America, in New York, and came back to Ireland. And then they went to London and did the squat scene there, and that’s how we knew them.

EB: Pretty multi-national project, I didn’t realize.

JR: Yeah, I think they’re half Irish, half American. I can’t remember which one, but I knew as a child they were in America, so they had slightly different music taste. It’s always interesting, the people who grew up in America who are British but had extra records the rest of us don’t have. Ian Ashbury is the same, he grew up in Canada and was always into Led Zeppelin and groups like that—which I like now, but at the time you wouldn’t even listen to Led Zeppelin if you were a teenager in punk. But people like him, because they had been in America, sort of helped to cross-pollinate it. He he’d be into post-punk like Metal Box by PIL [Public Image Ltd], Crass, and Led Zeppelin, which at the time seemed like an impossibility, whereas now it makes sense. Because he’d been to America, he could have that mindset, but growing up in the damp, wet claustrophobia of Britain of the late seventies, Led Zeppelin felt like an alien band! Too much sunshine in the music.

EB: Are there other examples like that of folks in the UK music scene who maybe come from North America and have a different sound because of it?

JR: There were a few that went there, like for a year, or even went for a holiday there and came back with different records. There was definitely a time in punk when it was very British, in ’77 and ’78. The Ramones, everyone liked The Ramones actually, out of the American bands. Television, Talking Heads, people liked them, but they weren’t massive at the time. Blondie would get bigger…but punk seemed a very British thing, if you were British. The British version of punk was quite different, and we were always keeping up with the latest bands to come out of Britain—not as a patriotic things, but because there were so many of them and we were trying to keep up with it. It was like every week five different great seven inch ingles would come out from different corners of the country. That would be all the music you ever needed, so you wouldn’t be thinking, “ooh, I wonder what’s going on in L.A.?” I remember when British bands played L.A., they would have American punk bands supporting them, and it seemed really weird then, people would go, “I can’t believe there’s punk bands in Los Angeles, how bizarre!” Now it’s changed, the story of what punk is. A lot of teens in punk now think The Misfits were one of the really key bands at the time, but no one [in the U.K.] had ever heard of them. I just knew the name, but had no idea what they looked like or sounded like—their records just weren’t available over here. It wasn’t until about ten years later that anybody heard them.

EB: I often think about how media travelled way slower across the Atlantic then, like the original Star Wars releasing several months after it had in America.

JR: Yeah, or records would come out months apart, wouldn’t they? The American release date would always be different. Can’t do that now, because everyone would just go on the internet to find it!

EB: I’ve heard much of England’s cultural rivalry between North and South, or like the Londoners versus everyone else, so I suppose when Manchester became hip that was a defining cultural pride moment and a first for the North?

JR: Yeah. Well, obviously, Liverpool was first with The Beatles…there were small regional scenes after that, but Manchester was the first, especially in the post-punk era. You could argue that post-punk was invented in Manchester, that re-defining of punk, and it became very prominent throughout the eighties. Like I say, we built the whole city on it—instead of “we built this city on rock and roll,” it’s “we built this city on indie rock!”

EB: So I hear you were involved in indie journalism for twenty years before starting Louder Than War magazine in 2010 and a corresponding festival soon after. What made you wanna start them?

JR: Well, I was writing for other websites and I had too many ideas. I thought it’d be easier to do my own. And it was gonna be a blog first, but a lot of other people joined me, so it became a website. And then from that, a publisher said, “you wanna do a magazine?” and it became a magazine as well. So, a lot of happy accidents, really. Like anything in music, there’s never really a complex, long-term masterplan. [chuckles]

EB: Very useful creative strategy there. I’m an author, I like to start writing stories without knowing the ending and think of it like a jam session.

JR: Yeah, your life becomes a free jazz improvisation!

EB: Now here’s a question I like to wind down with. It’s a bit bittersweet to talk about touring in this particular year, but I was wondering: do you have any especially mad, wild, bizarre stories from touring or performing you could share?

JR: Yeah, quite a few really! We toured Eastern Europe before the Iron Curtain came down, that was quite an experience. One I always remember is, at our level, you would always stay with other people because you couldn’t afford hotels for a long time. We stayed in this house, and the people who put us up, they took loads of acid and they had a swordfight, so we thought, “fuck this!” and went upstairs and barricaded ourselves into the attic and went to bed! There was a lot of banging and crashing all night, and we went down next morning and it was just blood all over the walls. All the doors were open and nobody was in the house. We just got into the van and drove off thinking, “what the fuck? What happened to those people?” [laughs] Never found out. Don’t know if they ended up in hospital, or if they faked it just to freak us out a bit. It was just bizarre, like the Mary Celeste with blood!

EB: Wow, that’s like something you’d see in a movie about a band’s misadventures…I guess the lesson there is, don’t keep sharp weapons on hand during a psychedelic trip!

JR: The lesson of that is, you have to know how to board the door so no one can get into the room! We managed to find bits of wood to block it with. And what happens is, you’re so tired on tour, that instead of getting in a van and going, “fuck it, we’ll just get a motel, there’s only one leg to go,” you go, “fuck it, I’m knackered, let’s board the door and go to sleep on our sleepy backs!”

EB: And hope they don’t kill each other or you.

JR: You have this weird lack of concern…you know, it’s more important to go to sleep than the fact someone might burst in with a massive sword! Tells you a lot about the way your head gets on a tour.